Simulation Training Profile: Chris Hearn, Memorial University

Memorial University in St. Johns, Newfoundland & Labrador, Canada, is a microcosm of how this unique regional cluster has parlayed its geographic locale and harsh, unique operating conditions into world leadership in the maritime, offshore energy and subsea tech spaces. An alumni, a professional mariner and now the Director of the Center for Marine Simulation, the Fisheries & Marine Institute at Memorial University, Chris Hearn has his hand on the pulse of the tectonic changes reshaping maritime and offshore energy simulation training today. From artificial intelligence to autonomy to fuel transition, Hearn and the Center for Marine Simulation are invested today to help train the current and new generation of seafarers.

While Chris Hearn is a graduate of the Memorial University nautical sciences program, he never anticipated being back at his alumni as the Director of the Center for Marine Simulation. His post-graduation career took him to sea, at first as a third mate on through to captain, sailing domestically and abroad under a variety of flag states on a variety of ships, from operating ships in the Arctic to tankers to cable layers.

“I came ashore first as Marine Superintendent, which was interesting in that when you're onboard, you're always wondering, "Why are we doing this?,” said Hearn. “When you're on shore and dealing with all the other sides, you get to [literally] see a [the many pieces that make up the other side], helping to understand why decisions are being made.”

Coming ashore put Hearn in touch with all aspects of marine operations, and he gravitated toward the training side. “Coming from Newfoundland, I can tell you there was nothing worse than getting off the ship and trying to make your way home, only be diverted to go fly somewhere for training,” said Hearn. “So when an opportunity came for a change, I came back to the institute to take over as a director at the [simulation] center, and I had the mindset that we can do anything here in terms of training and simulation. Nobody needs to leave here [to get training], and in fact, people can come here to obtain job training.”

With his education plus his career experience at sea and on-shore, Hearn saw the new opportunity as the perfect chance to leverage the investment already made in the simulation center with the cumulative experience of the Newfoundland & Labrador cluster, which has a unique proximity to the ocean and the Arctic that has given generations of seafarers and companies first-hand experience working directly in some of the world’s harshest conditions. “I saw the opportunity to leverage that into more special type applications that really reflected the operating conditions that we face here in Newfoundland in terms of harsh environment, the challenging conditions, and how people react in really high stressful situations,” said Hearn. “I always say that anybody with the time and money can buy all this [simulation equipment], but it's how people use it, how they overcome the shortcomings that are inherent to simulation to make it more compelling.”

With that, the center has a fairly modest 400 students coming through in a given year, but that doesn’t count the companies that come in and rent the entire facility to prepare for a complex project.

“Some might say that [number is] a bit small, but for our facility, given what we're doing, that's a pretty good number,” said Hearn.

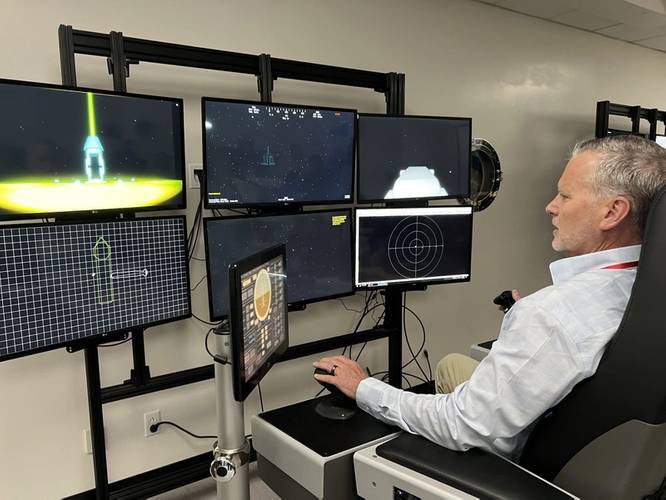

Chris Hearn, Director of the Center for Marine Simulation, Fisheries & Marine Institute, Memorial University.

Chris Hearn, Director of the Center for Marine Simulation, Fisheries & Marine Institute, Memorial University.

Simulation Technology Evolves

Since Hearn started his position more than 15 years ago in 2008, there have been “several waypoints in terms of [simulation technology] improvements that I've seen,” said Hearn. “Simulation technology vendors generally have a lot of similarity between them, what they're delivering and their customer service. There's a lot of parity there. You have some new people coming from the gaming technology and gaming background, because they've seen this opportunity now to bring some of the really interesting stuff. I've certainly seen improvement in the visual engines, making the visuals richer and more realistic; like the cloud shadowing and the way the water curls, for example.”

As in most aspects of business and life, the details matter, and the inclusion of small points that closely mimic nature are critical to keep trainees establish presence and believe that they are in fact on a vessel.

“I can also say that there have been improvements in the fidelity of the modeling of ships, the modeling tools themselves have dramatically increased,” said Hearn. “The ability to produce full 3D models is quite a powerful thing. Now we have the ability to build a one 3D hull and include the tanks and be able to adjust fluid levels in the tank, and then adjust the trim and draft. That's a powerful tool, because it not only reduces the amount of ships you actually have to build, but it also improves the fidelity of the ship you are building.”

Another improvement has been with the fidelity of controls in the instructor station, who have now more than ever the ability to make small, nuanced changes to adjust something as simple as daylight, for example, “and to make changes that would reflect what people would actually see, and be able to interact closer inside the model itself is much better,” said Hearn. “To have the ability to swing and maneuver cranes and ship's equipment that people would be expected to use onboard, that's tremendous too.”

Not only can the center combine its cumulative simulation assets into one project, it can connect too to a facility remotely, to dramatically enhance the scope and realism of a given operation.

“The big simulation vendors recognize that their clients are giving a lot of feedback, and they've also recognized that they can distribute simulation now,” said Hearn. “They can do simulation on the cloud. The engine is essentially on the cloud, you can pull data down to a laptop and have a very good high-fidelity simulation. That was unheard of 10 or 15 years ago, but it's there now, which makes it a much more distributed system. So you and I can be here pulling a simulation event out of the cloud to run on our laptops and be in the same scenario. That's pretty profound.”

Hearn’s simulation center is comprised, simply put, of a lot of equipment.

“The center’s main focus is around three Class A ship's bridges: the Full Motion Bridge, the Offshore Operation Simulator, and the Heritage Bridge,” said Hearn. “The Full Motion Bridge, which you were on, and the Offshore Operation Simulator are both sitting on these six-degree motion beds; it moves just like the ship will move, whether it's in a storm on the Grand Banks or you're battering your way through Lancaster Sound in ice, everything is replicated there. The Heritage Bridge is very specialized towards the shuttle tankers which serve the offshore industry, and the big three bridges are interconnected.”

In addition, Hearn and his team can also connect additional simulators, such as the full mission engine room simulator, the full mission ballast control simulator for an offshore drilling rig and several additional smaller units to deliver the most realistic training scenario.

“One of the unique things about that interoperability, that connectivity, is that we run large multi-party exercises all in the same scenario,” said Hearn, “which [is a big assist when planning big offshore structure] tow-out projects.

Ship to ship operations, with tankers coming alongside to load, utilizes multiple bridges, too.”

Image courtesy Memorial University Maritime Simulation Center

Image courtesy Memorial University Maritime Simulation Center

Planning Ahead

Though somewhat remote and unique in experience, the maritime and subsea professionals in St. Johns, Newfoundland & Labrador face the same megatrends driving maritime: energy transition; digitalization; automation and autonomy. When Hearn looks at the landscape around him, he sees artificial intelligence and the increased use of autonomy as pervasive trends that will continue to evolve and change not only the role of mariners on ships but the training they receive. That said, with those two, he sees maritime cybersecurity “as the gorilla in the room.”

“With AI, it’s finding out how it's going to be used and when it's going to be used,” said Hearn, noting that as of now there are far more questions than answers. “Does AI assist with collision avoidance? Does AI assist with cargo preparation and cargo loading? Does AI work with weather routing and navigation or voyage planning? How do those things actually look? Where is the AI sitting to? Is it onboard the ship? Is it a tool? Or is it almost like another crew member not under articles, but it's there to be used? I'm very interested to see how that plays out.”

When it comes to autonomy, Hearn points out that there is autonomy onboard already: “the good old autopilot versus autonomy 101, and unmanned engine rooms and these sorts of things.”

“[To be clear], I am absolutely not advocating for replacement of people onboard the ships, and I don't think that'll happen realistically,” said Hearn. “We may get to a point where you have a combined scenario where we have the smaller MASS operating in areas where there are people onboard; I think that's the more likely scenario. But autonomy is present and it is growing. So here at the Marine Institute, we're interested in how autonomy is played out in terms of remote operations.” To that end the Marine Institute is setting up an autonomous test zone at one of its facilities to help test the use of MASS in different crewed and uncrewed environments.

An he mentioned, the ‘gorilla in the room’ is cybersecurity with an inextricable link to automation and digitalization. “As I said to somebody the other day, a rudder angle indicator doesn't care where the information is coming from, its job is just to report what the rudder is doing,” said Hearn. “Using the simulators as part of the training to allow people to experience that is a really interesting opportunity. We're playing our way into this bigger thing around the cybersecurity, maritime cybersecurity, and how we can participate with other agencies or entities.”

Last, but certainly not least, is the fuel transition and the inclusion of new fuels – LNG, ammonia, hydrogen, amongst others – to the shipboard environment. “Again, for the propulsion plant, for the marine engineering program, how do they deal with changing fuel sources, preparing for effects of power management onboard the ship, and that interconnection between what the bridge is asking to have done and what the propulsion plant needs to do.” To keep pace, Hearn and his team will add components or new engine models that can represent – whether it be ammonia or hydrogen, or a combination fuels, how that works. And again, how do the skills of the people coming into the industry now [and for the ones that are already here] … how do their training need to be changed?”

It Takes a Village

The Newfoundland & Labrador maritime, subsea and offshore energy community is truly unique in its collective experience and collaboration, a fact hammered home time and again when you visit leaders and companies where they live and work or at trade events globally. Memorial University sits as a central hub, and world-class facilities like its Center for Marine Simulation an indispensable driver.

The reason that the province developed such an array of unique maritime expertise is actually fairly simple: they had to be.

“We have a long history of maritime trade, including the fishery and through to what we have now [with a long-established offshore energy industry],” said Hearn. “We have this in our DNA, it's part of what we are. So there's this connectivity between all these different entities.

What has happened is we've grown this tech sector to be primarily focused on the maritime and oceans industries because we needed to. There were opportunities to grow it here because a lot of technology that was available – or not available – didn't reflect, or couldn't deal with [our unique] operational challenges, the reality of our conditions: this mixture of weather, ice, sea state and isolation, as well as the variability and quick change in the weather patterns here.”

“We had a provincial government that recognized that very early, but again, it reflects life here. We are innovative by nature because we had to be. I heard a great quote one time about Newfoundland & Labrador: it has a landscape that makes you want to live up to it, but it doesn't provide you the resources to do it! We've had more than 500 years of living here, and because we're isolated, we had to grow something here in order to be able to deal with things.”

When people first think of Newfoundland & Labrador, it’s a good bet that the first thing they think of is not technology. But with a proven track record and leaders like Chris Hearn, that is changing fast now.

“The companies that grew out of research projects, that are either at the university or here at the institute, whether they be in the ocean tech or whether they be in fisheries and resource gathering or they're in maritime or offshore,” said Hearn. “Radar systems [like Rutter’s] that are able to do an amazing job in ice, came out of projects and then grew into companies that are now very successful and doing work all over the world. You have this self-sustaining circle of the education and training pieces, like we would do here at the institute or at the university, spilling out these really bright minds of these people who are working with the industry, and see a really good idea and say, "I have to do that."

Then, to support all of that you have the groups like Oceans Advance and the techNL’s and these other associations that are really blowing air into this fire that's growing here all the time for the tech sector. It's this combination of the need to do it and the want to do it that sustains it in an isolated place with a small population. We're not that far away, but we're far enough that it drives the spirit of “let's find a way to do this.” “What has happened is we've grown this tech sector to be primarily focused on the maritime and oceans industries because we needed to. There were opportunities to grow it here because a lot of technology that was available – or not available – didn't reflect, or couldn't deal with [our unique] operational challenges, the reality of our conditions: this mixture of weather, ice, sea state and isolation, as well as the variability and quick change in the weather patterns here.”

“What has happened is we've grown this tech sector to be primarily focused on the maritime and oceans industries because we needed to. There were opportunities to grow it here because a lot of technology that was available – or not available – didn't reflect, or couldn't deal with [our unique] operational challenges, the reality of our conditions: this mixture of weather, ice, sea state and isolation, as well as the variability and quick change in the weather patterns here.”

Chris Hearn, Director of the Center for Marine Simulation, Fisheries & Marine Institute, Memorial University

Photo credit GT