SS United States: Leading Lady to Damsel in Distress

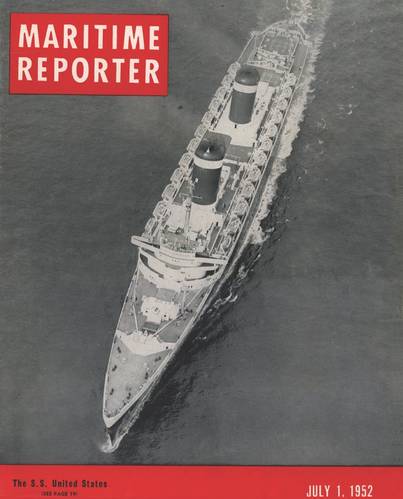

Once queen of the express liners, and the fastest, safest and biggest passenger liner in history, the SS United States today quietly awaits rescue from a pending cruise to the scrapyard.

The Big Ship the Big U, the one that didn’t sink. The S.S. United States, still the fastest passenger liner ever and enduring symbol for many of American post-war industrial might and ingenuity, is today more aptly called “the Lady in Waiting.”

She is waiting for a rescue that may never come from an appointment with the scrap yard looming large on her summer schedule. And that would be a shame according to her many supporters, not the least of which was the late newsman and sailor, Walter Cronkite.

“It [current state] is a crime against ship building, a crime against history,” said Cronkite, himself an American legend, in the 2008 documentary, SS United States, Lady in Waiting. “It was tear-jerking to see it just laying up there in that yard and gouging to pieces and nobody caring. Its restoration would be a restoration in American pride, in something America should be very proud of,” he lamented, over footage of the once proud liner.

To some, the ship, which was once the standard to which other express liners aspired – is today a rusting, gutted hulk, a mere shadow of her former self. On some level that is true, but the ship retains her sleek lines, trademark hull profile and famous stacks, and more importantly, her place in not just maritime history, but American history.

Everything about this ship, considered a technological wonder in its day, incited awe. It was, in many ways, larger than life – from its famous architect, William Francis Gibbs, to the outrageous size of its naval subsidy, to its compact, high-octane propulsion system, to its ultra light aluminum superstructure, propeller strategy, size, unparalleled attention to safety and the greatest power-to-weight ratio ever produced in a commercial passenger ship.

Capturing the Blue Riband

Overshadowing all that is its greatest claim to fame - its record-breaking speed. On its maiden voyage in July 1952, the United States shattered speed records crossing the Atlantic and back (see related story on page 35), ripping the fabled Blue Riband prize from the holder of 14 years, the R.M.S. Queen Mary, and holding onto it for life – 62 years and counting. “The great mystique was her power and speed,” notes Greg Norris, treasurer of the U.S. United States Conservancy, a non-profit group spearheading the campaign to save the ship, and a one-time passenger on the ship. “Essentially what Gibbs did was to shoehorn an aircraft carrier power plant into this fine, narrow, long hull.”

“It was HUGE when an American ship took the record,” says Arthur Taddei, who served as a junior engineering officer on the United States. “That’s why people were so passionate about it. It set a new standard. It was like the Constitution, which changed naval warfare. Of course, when something comes out with huge red, white and blue funnels, that makes it a very dramatic symbol of this country.”

Adding to its allure, the whole package came veiled in a tantalizing wrapper of secrecy. Lessons learned from the close of World War II when the U.S. had to rely on British ships to ferry servicemen home, tensions building in Korea and the frosty early days of the Cold War, convinced the U.S. Navy of the need for a passenger liner that could be converted quickly into a troopship. But it wanted more. Naval requirements for speed, safety, redundant engine rooms, heavy compartmentalization, insulated wiring, dimensions, etc., both dovetailed nicely with Gibb’s own wish list, and ensured that many parts of the ship design would remain classified into the early ‘70s. The SS United States was the first passenger liner to be built almost entirely in drydock – far from prying eyes.

Those demands heavily influenced the design, and also pushed up the cost of the project to the point where Gibbs was able to convince the government to pick up two-thirds of the cost $78 million, with the remainder to be paid by the operator, United States Lines. As for the secrecy, Gibbs wasn’t above using it to feed the ship’s mystique, and he preferred to keep his design under wraps, even from the Navy.

“Mr. Gibbs was extremely proud of that ship. It was his key piece of work in his lifetime. He wanted to keep [the design and construction] secret. In fact, he was very anxious to keep the government out of it as much as he could, “ said Prof. Jacques Hadler, a researcher for 31 years at the David W. Taylor Model basis, 17 of them as head of hydrodynamics, and a former Dean and currently part-time professor at the Webb Institute. Considered the nation’s leading expert on conventional propeller design, Hadler got his start in the Navy working on the speed trials for the United States, and for the men who redesigned her propellers.

But the real wonder of the ship lay not in just the individual components, but more in the way Gibbs took pieces of existing technology, and pushed or deployed them to the max, weaving together a whole much greater than the sum of its parts to accomplish his goals of faster, lighter, safer.

“The lesson she suggests by her very presence, is that anything is possible. We don’t have to have all the answers, we need only look back at the ingenuity of our ancestors for ideas and inspirations as we confront new problems and redefine old ones,” observes David MaCaulay, author of series of books on how things work or how they were built. A member of the Conservancy, he immigrated to the U.S. on the United States as a child and is currently writing a book with the ship at its center.

“I compare it to the space shuttle. We were able to do something no other country was able to do in the construction, design and build of the ship – things no other ship in the maritime world has been able to do or do since,” Joe Rota, who worked on the ship in a myriad of positions, culminating as ship photographer, and is currently a Conservancy board member. “She was an absolute marvel. She was never late, and she never needed a repair.” Heck, she could sail for 10,000 nautical miles without stopping for any reason. No other passenger ship could do that.

Key Elements of the Ship

The reliability of the whole in turn, speaks to parts, and to issues that Gibbs and the Navy focused on.

For starters, at the heart of the ship was the carrier-class propulsion system and power plant. At the insistence of the Navy, the vessel had redundant engine rooms equipped with eight IOWA-class Babcock &Wilcox boilers operating at 1,000 psi and 975°F, always with four online and four offline. In contrast, the QEII had three boilers in constant use, which is why it always had turbine trouble, according to Norris.

The Big U had four sets of Westinghouse double-reduction geared steam turbines, rotating at 5,240 rpm; and 250,000 shaft horsepower (SHP). In addition, there were six 1,500 kilowatt steam turbo generators on board, backed by two 250 kilowatt diesel emergency generators. Those boilers ran on water distilled on ship, and nothing else.

Throughout her service, the United States cruised at an average of roughly 30 knots, about two thirds the maximum speed of 38 knots she was actually capable of – a top speed that was classified throughout the ‘60s. “You had to keep the speed low enough so as not to increase the fuel consumption or you’d run out of gas. We had plenty of capacity but the last 5 knots double fuel consumption,” explains Taddei. Moreover, the ship only needed 130,000 SHP, but the Navy wanted more power in order to protect future troops from waiting subs. “If you are going slow, you are sitting target.”

Contributing to the speed were the signature hull and a four-screw propeller design.

Gibbs based the hull on an existing design known as the Taylor Nu. 40 hull, and modified it further, creating a knife-like stem, tiny bulbous bow and rounded cruiser and transom stern combination using a special lightweight steel and building in 16 watertight compartments, according to Norris. Taylor was a marine engineering who did a lot of pioneering work on hull design. “She had better watertight integrity than other ships of the day. If she had a thing like the Titanic, she would not have sunk. Up to 13 compartments on the ship could have been flooded and the United States would have maintained watertight integrity,’’ says Charles B. Anderson, Conservancy president, a maritime attorney and the son of the longest serving commodore of the ship, John W. Anderson.

A key safety feature was an elaborate labyrinthine of wing tanks built into the double hull. If the ship was punctured on one side, the tanks could be cross flooded starboard to port or vice versus, allowing the ship to remain on an even keel. Proof that it worked came from an incident involving the Gibbs-designed S.S. Malolo, which collided with another ship and took in over 7,000 tons of water and yet stayed upright and made it back to port.

“If you think about the recent Costa Concordia accident, where the ship keeled over and they couldn’t launch lifeboats properly on their side, you see the value of Gibb’s idea,” adds Norris.

It had an extraordinarily long and narrow beam and was configured to have less resistance from the water at top speed, Anderson adds, noting “It left virtually no wake.”

The United States sped across the Atlantic on its maiden voyage on four 18-ft, manganese-bronze propellers - two outboard four-bladed propellers and two inboard five-bladed propellers – said to be the first used of mixed blades, designed by Elaine Kaplan of Gibbs & Cox. The propellers did their job on the record-breaking trip, says Hadler, but when the ship came back into port, they had severe propeller damage. “One was so badly eroded, at the root you could see through 8 or 9 inches.” As a result, the propellers ended up being designed three times to address two problems: cavitation, erosion and vibration. More blades can deliver more power, but fewer blades are more efficient and create less turbulence. “It’s something we in later years, by the late ‘60’s, got a handle on,” Hadler says.

Taking off the weight

More easily solved was the weight issue. And the primary answer to that was an almost obsessive use of aluminum through the ship, both for its super structure and in its fittings, furnishings and décor.

While shipbuilders began using aluminum more during WWII – because it was lighter than but as strong as steel – its use was limited because it can’t be welded, it weakens when heated and it doesn’t mate well with steel. Gibbs was not dissuaded. He not only built his entire superstructure from aluminum – extremely unusual at the time – to make the ship as light as possible, but he used it everywhere possible, driving his decorators crazy while consuming 2,000 tons of the stuff. It was the largest amount used in any project in the world until the Twin Towers were built in the early ‘70s, according to his granddaughter, Susan Gibbs, executive director of the Conservancy. Gibbs and his team figured out how to outsmart the corrosive effect the two metals had on each other. “When steel and aluminum met, they didn’t like each other, so they had to put a layer between the two – neoprene,” says Norris. Frozen rivets got around the welding and heat issues.

Another example of where Gibbs took existing technologies to an extreme is Safety. “Gibbs was a fanatic about safety, he had an absolute paranoia about fire,” says Norris, noting that the naval architect was deeply affected by the 1934 burning of the S.S. Morro Castle, which killed 137 passengers and crew. The disaster spawned improvements in ship safety overall, but Gibbs left nothing to chance, going well beyond all the safety standards of the day.

Everything had to be fireproof right down to the paint and the bedding, leading to the use of chemical retardants, fiberglass and Maronite, panels encasing an asbestos layer that coated the ship. He famously banned wood from the structure, “except for the piano and the chopping block.” Not that Gibbs didn’t try to get Steinway & Sons to build an aluminum piano. Instead, Steinway proved to Gibbs his pianos would not burn by pouring gas on top and light one up in a demonstration.

Other safety features included more lifeboats and rafts than the ship needed, and a remotely controlled from the bridge system that would close doors in the event of a fire, containing damage.

All combined, the super-secret hull design, compact state-of-the-art engines, 250,000 HP, boiler system with its super-heated dry steam, the five-bladed propellers, the super lightweight all-aluminum super structure, the unheard of attention to numerous safety measures deployed within and about the ship and it’s celebrity clientele – are just part of what created a legend. But it wasn’t enough to fight the continued march of technological progress.

Up, Up and Away

In a nutshell, commercial air travel, which debuted in 1958, and progressively improved and expanded through the ‘60s, killed the trans-Atlantic passenger liners. As Bob Sturm, another former engineer on the ship notes, “Six hours on a plane beats 4.5 days to New York or France.” Passengers voted with their feet, especially businessmen, for whom time is money.

Rising fuel costs and restless unions on the heavily staffed ships took their toll as well. “She consumed 700 tons a day in fuel. When it’s $2 a barrel it doesn’t matter, but in the end fuel costs began to escalate pretty dramatically,” said Norris. Tug strikes forced Commodore Anderson on more than one occasion to pilot his ship into the dock by himself.

One by one, passenger liners started dropping by the wayside. By 1969, the United States was sent home to dry dock in Norfolk, Va. in November; after a mere 17 years of service, she never sailed again.

Initially, she was mothballed by MARAD. Once the ship was declassified, the agency divested itself of the now white whale. After passing through multiple hands, being dragged to various ports and suffering several waves of gutting, the ship ended up in the hands of the Norwegian Cruise line, which had hoped to restore it back to a working ship. Ultimately the ship was sold in 2011 to the Conservancy, notably at a lower prices than could have been gotten from ship scrapper, financed with a donation from Philadelphia philanthropist H. F. Lenfest, a finance package that included two years of monthly maintenance fees, funds which today are gone. Today, the group relies on donations and revenue from the sale of precious metals in the ship to cover the $65,000 to 80,000/month in dockage, insurance, security and other costs while it tries to land a development deal to secure a future for the ship.

But the clock is ticking. To keep the ship safe until a deal can be worked out, ‘We need money, money, money,” says the Conservancy’s Gibbs.

An American Icon

Half the battle in raising funds lies is the difficulty in trying to articulate to a modern audience why The Big Ship is so important, laments Anderson, who sailed on the ship as a teen. “Most cruise ships today are more like floating hotels. There was no transatlantic air service in the ‘50s and most of the ‘60s. The big liners were used to transport not just vacationers, but business men and immigrants – it’s an important distinction that is completely lost on people today. It was a ship with a real purpose.

A dual purpose actually, although the ship only came close once to functioning as a military transport, when it put on standby during the Cuban missile crisis.

Conservancy members and fans of the Big U say the ship should be preserved as a symbol of American strength and technological know-how, as well as one of the few remaining examples of a once proud U.S.-flagged merchant marine. “This country has lost its connection with its maritime history and the the importance of shipping. We don’t have our own ships. We rely entirely on foreign ships to carry good and passengers to the U.S. Aside from the Jones Act, there is virtually no U.S.-flagged merchant marine left,” said Anderson. While supporters also liken the impact of the ship to that of the first space shuttle and other historic treasures, they also acknowledge the difficulty in try to preserve a piece of history that is three football fields long.

Gibbs and other board members talk about developments encompassing hotels, restaurants, a museum, educational and convention facilities etc. The fact that ship externally remains intact while the interior has been gutted and stripped of its asbestos is a plus for any developer with deep pockets and imagination. And the project is not without precedent. The S.S. Rotterdam was renovated, returned to her namesake city in Holland and re-opened in 2010 as a combination museum/hotel and school for vocational training. It has since been sold to a hotel chain. “The United States today is a blank slate; the possibilities are endless,” said Gibbs.

But time is not on their side. According to Norris and Anderson, efforts to find a project is caught in a Catch-22 of developers who don’t want to commit unless they know where the ship will based. Cities don’t want to provide pier space unless they know developers are committed. And once a site is found, before the ship can be renovated, a decision has to be made from a regulatory aspect as to whether to treat it as a ship or a building. “The sad irony is that an organization that has worked so hard to save this ship is ultimately going to be the one to wind up scrapping her if that happens,” said Norris.

Truth be told, it doesn’t look good for the old girl. But as William Gibbs would be the first to say, obstacles are just that. It doesn’t mean they can’t be overcome. The S.S. United States had a spectacular past; who’s to say she won’t surprise the world again, with a spectacular rebirth. As Gibbs would say, “Here’s to the Big Ship.”

Maiden Voyage First Time is a Charm

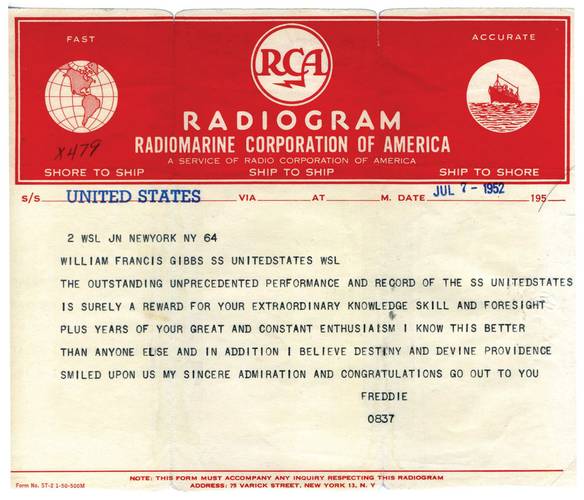

On July 3, 1952, the SS United States steamed out of the Ambrose Channel in New York Harbor and headed off into the North Atlantic on her first voyage to Le Harve, Normandy, and then to the Port of Southampton on the southern coast of England by way of Bishop Rock, off Cornwall. After a slow start due to fog, Captain Harry Manning made up the time with an average eastbound speed of 35.59 knots, reaching Bishop’s Rock on July 7, in a then jaw-dropping three days, 10 hours and 40 minutes, despite encountering gale force winds and heavy swells. Even more awe-inspiring, the United States broke the record while using only two-thirds of her available power, never exceeding 158,000 SHP.

One side effect of her record-breaking speed could be seen in the bare patches on the hull, where the sea peeled the paint right off as the ship raced through the water.

The next day, she entered Southampton to tremendous fanfare from the thousands of cheering onlookers onshore and onboard a riot of various size craft, all sportingly saluting the American feat, despite the dethroning of its own grand ocean liner. Winston Churchill and the captain of the Queen Mary, which had previously made the same crossing in three days, 20 hours and 42 minutes, were among the many that sent congratulatory notes welcoming the American ship to the North Atlantic and hailing her success.

The United States eventually lost the eastbound speed record in 1990 to a British-flagged, empty wave-piercing catamaran passenger/car ferry.

On July 14, 1952, on the return to New York, the United States set a second record, completing the westbound crossing in three days, 12 hours, and 12 minutes, running at an average speed of 34.51 knots. With a symbolic 40-ft. blue banner flying high, she sailed triumphantly into port, accompanied by a raucous feet of smaller craft vying for the honor of escorting the new speed queen home (see photo). Fireboats sprayed water, thousands of people lined the waterfront. Four days later, the designers and crew were treated to a ticker tape parade in the city. The impact of the United States’ feat is sometimes compared to that of the launch of the space shuttle, which expanded once again our definition of travel and its limitations. In the days before commercial passenger air flight, transatlantic travel was critical, so critical that Churchill has credited passenger liners pressed into troop ship service with shaving a year off WWII. In that environment, the United States thrived for a good 17 years of flawless service, until she too was outgunned and left in the surf by the next revolution in transportation speed – hours instead of days - via commercial air service. “She just snuck in under the wire – the airplane was about to take it all away,” notes David Macaulay, author of series of books on how things work or how they were built. “By the end of the 60s, it was all planes.” Business travel, and ocean liners, would never be the same. The very attribute that Gibbs had worshipped – top speed – became the undoing of his life’s obsession.

(As published in the February 2014 edition of Maritime Reporter & Engineering News - www.marinelink.com)

SS United States Facts

Name: SS United States

Nicknames: The Big Ship, The Big U

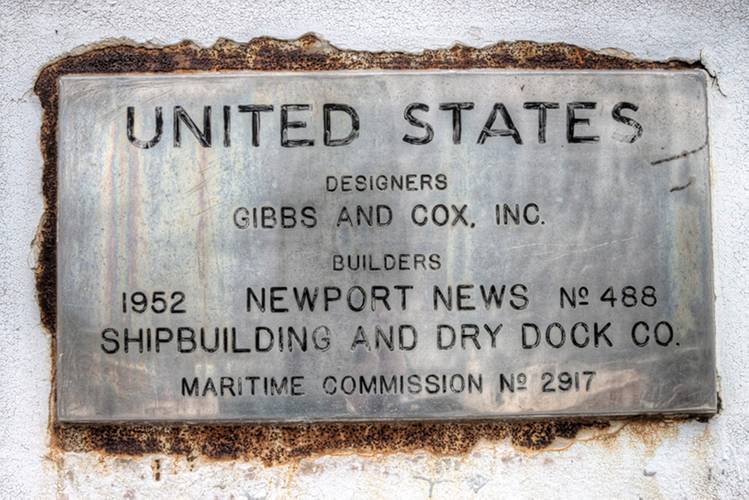

Designer: William Francis Gibbs (Gibbs & Cox, Inc. naval architects)

Builder: Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Co., 1950-1952

Operator: United States Lines Co., NY

Port of registry: New York City

Launched: June 23 1951

Maiden voyage: July 3, 1952

Years in Service: July 1952 – Nov. 1969

Voyages: 400 transatlantic crossings for 772,840 miles.

Cost: About $78 million - $28 million from United States Lines; $50 million from the U.S. MarAD (the ship had to be convertible in 48 hours to a troop ship with capacity of 15,000).

Length: 990 ft.

Beam: 101.5 ft.

Depth: 75 ft. Keel to top of Superstructure, 122 ft.; Keel to top of forward funnel 175 ft.

Draft: About 31 ft.

Total cargo capacity: 148,000 cubic feet

Funnels: Two, 65 ft. tall

Decks: 12

Complement: More than 3,000 passengers and crew

Speed: Cruising 30-33 knots, Max. 38 knots

Horsepower: 248,000 SHP (180,000 kW)

Electric plants: 6 x 1,500 kW steam turbo gen; 2 x 250 kW diesel emergency gen

Propellers: 4 x 18-ft, manganese-bronze propellers, over 60,000 pounds each. Forward outboard props have four blades; aft inboard props have five.

Bunker Capacity: 10,306 tons fuel oil

Distance without stopping: At 35 knots, 10,000 nautical miles or 12 days.

Hull: Comprised of 183,000 separately fabricated sections of 2-inch steel plating

Tonnage: 53,330 GRT; 29,475 net

Displacement: 47,300 tons at maximum draft

Classified Status:

Naval requirements for speed, safety, redundant engine rooms, compartmentalization, insulated wiring, dimensions, etc., led to a closed construction site, limited access on ship to key systems and a classified designation until the early ‘70s.

Hallmarks:

Aluminum (2,000 tons) superstructure, record-breaking speed and HP, subassembly construction, extremely sleek hull, unusually narrow beam, propeller system, Naval-grade propulsion, aggressive compartmentalization, virtually fireproof construction and furnishings, fully air-conditioned, ship-to-shore telephones in all staterooms, listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Record holder:

“Blue Riband” holder, given to the passenger liner crossing the Atlantic Ocean in regular service with the record highest speed. Set new record when sailed from New York Harbor to Cornwall, U.K. in 3 days, 12 hours and 12 minutes at an average speed of 34.51 knots. Return voyage also completed in record time, in 3 days, 12 hours and 12 minutes at an average speed of 34.51 knots.

Propulsion:

Separate engine rooms equipped with 8 IOWA-class Babcock &Wilcox boilers operating at 1,000 psi and 975°F; 4 sets of Westinghouse double-reduction geared steam turbines, rotating at 5,240 rpm, which produced up to a combined 247,785 shaft horsepower (SHP).

Current owner:

Acquired in February 2011 by The SS United States Conservancy, a non-profit dedicated to saving the ship. Purchase ($3M) and maintenance funding ($300,000) were provided by Philadelphia philanthropist H. F. Lenfest.

Maintenance costs:

In 2010, then owner Norwegian Cruise Lines put annual maintenance costs at $800,000/ year. The Conservancy spends roughly $65,000/month (some estimates go to $80,000-$100,0o0) in dockage, insurance, security and other costs.

Current Status:

Berthed in Philadelphia at Pier 84 since 1996, awaiting final disposition - development or scrap yard – with a summer 2014 probable deadline.