The sea is not empty.

Ports, harbors and waterways have to manage an ever growing volume and mix of recreational activity and heavy commercial activity - at times across the same compact waterspace. This creates a series of challenging marine planning requirements that need to be addressed. While land use is often well zoned and tightly regulated, there is frequently limited designation of waterspace outside of specific fairway / anchorage demarcations and protected ecological marine areas.

This lack of designation may ultimately lead to the stagnation and the unimaginative development of waterspace usage as well as land / water interfaces. Richard Colwill, Managing Director, BMT Asia Pacific discusses the issue and suggests how effective Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) can contribute to sustainable future development.

In order to optimize waterspace, the key watch-word is integration. Integration is vital because it recognizes the potential uses of multiple activities across waterspaces and at varying depths. It also considers the needs of different stakeholders which may be competing or complementary, and provides a flexible framework to accommodate future changes. Such a management framework needs to be built on extensive stakeholder knowledge of existing constraints, but also recognize that plans are not static and should be an enabler of future opportunities. Consequently, there is the need to be able to say “Yes” to valuable uses and “No” to disruptive uses in a consistent and knowledgeable manner.

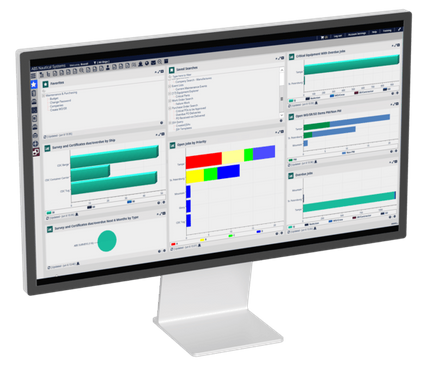

We need to be able to adopt and apply tools that can collate the required knowledge to reconcile the many uses of waterspace. Building from a foundation of data and information it is necessary that these tools provide a disciplined structure and allow linkages to be made, connections realized and decisions identified and shared (this last point is important, as it provides transparency to the decision making process and allows all stakeholders to understand and weigh the competing demands of waterspace).

This is where MSP comes in. A ‘textbook’ definition of MSP is: an integrated public process to analyze and allocate the use of marine waterspace, manage interactions between users, and identify and achieve economic, ecological and social objectives. In practical terms, MSP is an interlayering of potential waterspace uses, allowing numerous activities to coexist. It is a structured approach to deciding what mix and combinations of services and goods would be best produced from the marine areas, (see Table 1). It is also a framework for management across all sectors and among levels of government and a platform to actively involve the public and create a first stage plan.

The crucial element of developing a plan under MSP is to identify compatibility and a hierarchy of needs. The most basic analysis will demonstrate that many marine areas cannot simultaneously meet all demands for use (for goods or services), and that the value of marine space cannot be entirely expressed in monetary terms. However, if a solely single-sector analysis (i.e only looking at needs from one perspective) and allocation is conducted, then there may be inadequate consideration of other uses, leading to a chaotic pattern of overlapping and conflicting zones and ultimately conflicts between users. Allocation on a case-by-case basis also means that decision makers often end up in a reactionary role. This requirement to integrate the needs of all users is a pivotal element of MPS.

Furthermore, it is necessary to review waterspace and identify which marine areas are most important, both economically and ecologically, observing current conditions as well as with one eye looking towards the future.

Delivered by qualified and experienced practitioners, MSP provides a number of economic, ecological and social benefits. Streamlining and transparency in permit and licensing procedures make way for clarity over waterspace status for medium to long-term investment planning. Ecologically, the identification and demarcation of environmentally important areas permit a reduction in conflicts and a planning context for their protection. Lastly, society benefits from improved opportunities for community and citizen participation in the decisions that impact ocean space and economies onshore.

It is important to remember that real outcomes, not processes, are the goals of MSP. But bear in mind that establishing and maintaining continuous planning for marine spatial management will not be achieved unless all stakeholders, including decision makers, politicians, resource managers, bureaucrats and the general public understand the net benefits of planning – and this is where establishing good process is critical to success.

The sea is not empty and we need to show wisdom in our planning of waterspace usage.

Table 1: Managing interactions: Marine waterspace can provide a variety of goods and services, including:

Goods

•Fisheries

•Marine animals for recreation, e.g., dolphin watching

•Sand and gravel

•Marine minerals

•Other raw materials, e.g., building materials, traditional crafts

•Energy

Services

•Marine transportation routes

•Tourism, leisure and recreation

•Cultural heritage and identity

•Education and research

•Habitat e.g., nursery areas for fish

•Protected areas

•Waste disposal

•Aesthetics