Optimizing Port Arrivals Could Slash Voyage Emissions

A new study by UCL and UMAS, which analyzed ship movements between 2018-2022, found that optimizing port arrivals to consider port congestion or waiting times could reduce voyage emissions by up to 25% for some vessel types.

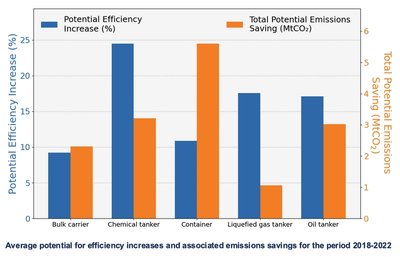

The average potential emissions saving for the voyages is approximately 10% for container ships and dry bulkers, 16% for gas carriers and oil tankers and almost 25% for chemical tankers. The study finds that these ships spend between 4-6% of their operational time, around 15-22 days per year, waiting at anchor outside ports before being given a berth.

Over the period 2018-2022, chemical tankers, gas tankers, and bulk carriers spent increasing waiting times at anchor before berthing, rising to 5.5-6% of time per annum, by 2022. Waiting times for oil tankers and container ships stayed approximately constant (around 4.5% and 5.5% respectively). Some of the increase in waiting times may be attributable to the port congestion caused during Covid-19 and by a post-pandemic surge in maritime trade.

The study also found that smaller vessels generally experience longer waiting times, though this varies by vessel type. Previous report by the authors, Transition Trends, has shown that poor operational efficiency is one of the main reasons for increased emissions in the period 2018 to 2022.

The waiting behavior stems from the common operational practices such as “first-come, first-served” scheduling and the “sail-fast-then-wait” approach—and is exacerbated by systemic issues such as port congestion, inadequate data standardization, inflexible charterparties (between shipowners and charterers), and limited coordination between the many wider stakeholders involved in a loading/unloading operation (port authorities, cargo owners etc.).

The study shows that the Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) regulation should consider all aspects of the voyage and not just the ‘sea-going passage’ as some have proposed, as it can incentivize stakeholders to come together to find solutions to reduce the GHG intensity of the ships across the value chain, instead of just isolating those parts where the shipowner or charterer are fully in control of. Limiting the CII to only parts of the voyage would mean that the well-known market barriers at the interface of ship-port operation would remain under incentivized and continue to persist, making the 20%-30% absolute GHG reduction in 2030, relative to2008, specified in IMO’s Revised Strategy more difficult to achieve.

Dr Haydn Francis, Consultant at UMAS, said: “Our analysis highlights that the no value-add emissions associated with port waiting times are a current and growing issue across the shipping sector. This is just one piece of the broader operational inefficiency puzzle that can be targeted to generate the short-term emissions reductions that will need to be achieved before 2030. By targeting these idle periods, the IMO can help unlock significant emissions reductions while also driving broader improvements in voyage optimization and overall operational efficiency”

The work also highlights the contribution of port congestion to system-wide inefficiencies. Port congestion has been highlighted by low-income member states, as a disadvantage to them and their efforts to decarbonize. Although unable to be looked at in depth in this study, this suggests that there could be links between efforts to find system efficiencies at the interface between ships and ports, and the efforts to enable a just and equitable transition, which are an important feature of the design of mid-term measures.