Illinois Waterway Closures: Look for the Workaround

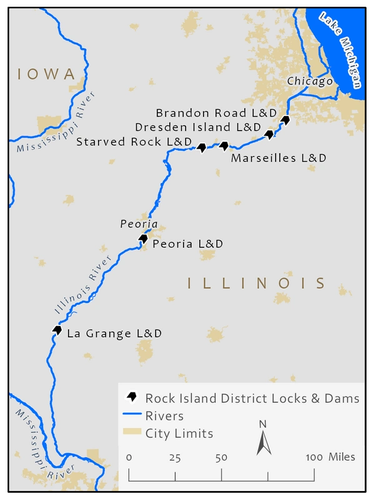

A set of complicated lock-and-dam projects on the Illinois Waterway, from Chicago to the Mississippi, has yellow lights flashing throughout the Midwest freight industry. In effect, the entire Waterway will be shut down next summer as the Army Corps of Engineers, Rock Island Division, starts some hefty replacement and maintenance projects, from LaGrange to Brandon Road locks and dams.

Officials advise maritime, freight and agricultural businesses to look ahead now, to prepare a logistics scenario that will be ready by July 1, 2020. Rock Island District anticipates the navigation industry could need two or more years to fully recover from the closures. It’s a good news/bad news story for the inland industry. Stakeholders have long complained that the work needed to be done, but the money wasn’t there. Now, it is.

The Illinois Waterway typically carries more than 29 million tons of cargo each year, including about 10 million tons of agricultural products and 4 million tons of fertilizer, according to the Illinois Soybean Association (ISA). About 60% of the soybeans grown in IL are exported. Waterways and barges offer two basic transportation advantages – low costs for bulk commodities and reliability. It goes without saying that those advantages will be under great pressure in 2020.

Ready or Not …

Maritime operators got an advance look at dealing with full closure last month, starting September 21, and scheduled to last until October 5. That’s when work starts at the Starved Rock and Marseilles locks to install sill beams across the bottom of the lock chambers. In addition, also at the same time, the navigation lock at Lockport, IL, about 30 miles from Chicago will be closed due to unanticipated miter gate repairs.

Importantly, the Waterway between the dams and locks will be open and fully accessible. It’s full transit that will be severely restricted.

The Illinois Waterway is old infrastructure, some might say ancient. The first phase of the Waterway project opened in 1933, with Lockport construction and the locks and dams at Brandon Road, Dresden Island, Marseilles and Starved Rock. All those facilities are in the queue for upgrades in 2020. Most work concludes next summer, but some remaining work is planned out until 2023 – 90 years after ribbon-cutting. The upcoming work should extend Waterway assets for another 25 years.

Concurrent timing is a deliberate part of the Corps’ work schedule, an approach with maritime and freight industry support. Officials are taking the stoical view about getting all of the work, or at least most of it, done at once. The general thinking is that, yes, expect headaches next summer and fall but it’s better to get this over with rather than drag on for years.

Around the Next Bend

Work at Marseilles and Starved Rock, requiring full closure, runs from September 21 to October 5. There are early lessons here already. One, the work was delayed from its original August start date because flooding made it impossible for USACE crews and equipment to properly access the sites. It is hoped that 2020 flooding will not be as severe. Secondly, maritime industry officials asked for the delay so that they could clear the waterway, so to speak, allowing freight to get to Chicago and still have time to return barges past Marseilles and Starved Rock. Importantly, after the locks reopen on October 5, the waterway will be open in time for harvest season.

The Summer of 2020 promises additional activity:

- July 1 is the projected start for the $117 million LaGrange Lock Major Rehabilitation project requiring a 90-day full closure to install new miter gate machinery. The Corps refers to the start at LaGrange as “the driving factor” for starting work at other sites.

- Starved Rock will also close on July 1 for 120-days, until October 30, for upper and lower miter gate installation and significant sill and anchorage modification.

- Marseilles, too, will close July 1 for 90 days for upper miter gate installation.

- With the Waterway “closed” (the Corps’ word) bulkhead work will start at Dresden Island and Brandon Road, requiring 14-day closures and 90-plus day partial closures; dates are not yet set.

- Peoria Lock will close for 60 days for routine inspections and minor repairs; again, exact dates are not set.

Looking farther out, to 2023, the Corps plans to return to Dresden Island and Brandon Road for miter gate installation, again requiring 90-day closures. But, importantly, this work is not yet confirmed, and remains contingent on a number of factors, including funding. Even after the bulk of the work is done in 2020, and after the Corps’ calculated two-year work break, significant work remains, although at a lesser scale.

Still, it’s not hard to wonder: how will millions of tons of agricultural products move to markets next fall with a fair number of barges sidelined? And, will the rail and trucking sector be able to take up the slack when demand spikes?

Getting Ready … or not

Interestingly, each September, the federal Surface Transportation Board schedules a meeting of the National Grain Car Council, established in 1994 as a working group to facilitate private-sector solutions and recommendations on “matters affecting rail grain car availability and transportation.” This year, the Council met on September 12, in St. Louis. The purpose of the meeting was to discuss rail carrier preparedness to transport yearly harvests.

Despite widespread awareness of the upcoming Illinois challenges, the Waterway shutdown is not on the Council’s agenda. People familiar with the Council’s meetings said that the Illinois waterway might be raised within an impromptu discussion, but it’s not a topic that would establish a closer look or expected next steps.

In 2014, the Surface Transportation Board opened hearings in response to complaints from farmers and the agricultural industry about poor rail service in western states, from Minnesota to Montana, a region where rail is the singular industrial carrier. Without competition, concerns about markets and prices are filed with the Board, where petitioners seek relief.

For farmers, 2014 rail service issues were serious and extensive; this was largely about failed service. One grain elevator, for example, expected to have 800 railcars per month for shipments, but just 300 cars were made available. Cars sat on tracks for up to 10 days. Overall costs increased due to rail non-performance. Some trains ran 20-30 days late.

The situation in IL next summer is not exactly analogous to the situation experienced in the western states – except for one important way: there won’t be much freight intermodal competition in 2020 in IL, at least for bulk freight shipments. Barges will be sidelined. Will rail provide what farmers expect and need in 2020? Look into that question now.

Likely, shippers will need to move commodities more frequently, in separate, shorter trips to finally reach a port that can accept material for shipment to St. Louis, say, or New Orleans. Or, a farmer between the Illinois Waterway and the Mississippi may arrange to work with a port on the Mississippi rather than the Illinois, despite a longer travel time.

Mike Steenhoek is the Executive Director of the Soy Transportation Coalition, which is comprised of thirteen state soybean boards, the American Soybean Association, and the United Soybean Board. The thirteen participating states encompass 85% of total U.S. soybean production.

Next summer’s Waterway work “is very much on our radar,” Steenhoek said when asked about his advice to members for dealing with the closures. One basic concern is that these transport issues are one more headwind for farmers.

Steenhoek and his team have met with the USACE many times to discuss the lock-and-dam work. Communication will be key. Steenhoek’s message: “If you (the Corps) err on over or under-communicating, err on overcommunicating. If you know you’re behind, let us know.” Steenhoek said shippers will move product to other waterways. He said farmers could sell to a local cooperative or find another market – a biodiesel facility, for example. In some instances, shippers will use trucks to bypass one site to get to a port unimpeded by the closed Waterway.

Steenhoek noted freight data showing a 200% increase in rail transport to New Orleans when flooding prevented barge service. People will adapt, Steenhoek said, and hopefully those alternatives will meet budgets and timing, especially, of course, with perishable commodities that surge into the system all at once, or close to it.

Separately, the St. Louis Regional Freightway is also closely monitoring the Illinois projects. The Illinois River meets the Mississippi about 50 miles south of the LaGrange lock and dam; the Rivers converge about 30 miles north of St. Louis. In a May press release, the Freightway noted that while industry is used to working around river closures on some rivers, it called the upcoming Illinois closures “unprecedented.”

In a prepared statement, Mary Lamie, executive director of the St. Louis Regional Freightway said, “It’s vital that industry members are aware of the plans, the timing and any steps they need to take in advance of the closures to help minimize the disruption to their operations or, to potentially be a part of the solution.” She added, “Shippers already route freight to the St. Louis region where the exceptional freight network means they benefit from lower distribution and logistics expenses and shorter travel times. We should have the capacity to take on more and be a part of the solution for those who will be impacted, if the planning starts early.”

Mike Toohey, President and CEO of the Waterways Council, Inc., perhaps said it best when he advised stakeholders, “Plan, be flexible and be ready.”

This article first appeared in the October print edition of MarineNews magazine.