Duty of Care

Data collection and monitoring helps measure the impact exposure of Workboat crew and passengers.

Professional powerboat users face an increased risk from injuries associated with the constant impacts they receive during their daily activities. It is not hard to imagine that constantly driving a rigid hull through a choppy sea will result in some uncomfortable moments, but much of the professional marine industry continues to pretend that there is no problem.

The term ‘Professional’ is important. If someone in their spare time wants to drive at maximum speed, exposing them to a risk of injury, then so be it. But the Professional user is not working for fun. They are out in all weathers using the boat as a tool to get them from A to B or to perform tasks. They should be protected from harm the same as a worker in any other industry.

In recent years, there has been plenty of discussion on the latest legislation that sets limits on the worker or paying passenger’s exposure to Whole Body Vibration (WBV) and Hand Arm Vibration (HAV), which in Europe is defined by EU Directive 2002/44/EC. Applied to all industries, including Construction, Mining and Maritime, this directive focuses on chronic conditions caused by long term exposure to vibrations which we define as those that infiltrate your bones and shake apart your cartilage.

The EU directive is undeniably essential. Advocators of improving health and safety for professional marine workers used the EU directive as the driving force for the introduction of better personnel management or the use of shock mitigation equipment to reduce injuries. Having been introduced and accepted in other industries, it was deemed to be the solution.

However, with the EU directive now in force it appears that the legislation could be construed as being flawed for use in the maritime industry. The required method of calculating WBV exposure is complicated and requires sophisticated mathematics. The vibration exposure limits seem unrealistic; by trying to enforce apparently unachievable targets, many in the industry now oppose the law.

Carl Magnus Ullman, CEO of Ullman Dynamics has recently published an article addressing the failings of the existing measuring standards. Visit www.hsbopro.com for further information.

The headline is that acute injury does not come as a result of vibration, but as a result of impact. The ISO standards chosen by the EU committee were used as they were the closest available, but they were developed for forestry machines and lorries where vibration is the major issue. We need to forget about whole body vibration and focus on impacts.

Protection From Prosecution

The UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE) recognises the perceived shortfalls with the EU directive and the problems in applying the stringent WBV exposure restrictions in the marine environment. The HSE will accept improvement to impact exposure when investigating compliance with the regulations, but this requires evidence that the employer has acknowledged the risks and taken steps to reduce their staff’s exposure to harmful impacts.

In conjunction with the HSE, the UK Maritime and Coastguard Agency has introduced a scheme that will provide exemption from prosecution to employers that cannot meet the exposure limits required by the EU directive, providing they can supply evidence of monitoring and an attempt to reduce their workers exposure to WBV and other harmful impacts.

Monitoring and Reducing Impact Exposure

Tracking an employee’s impact exposure does not mean that they have to stop working whenever it peaks. Most days it would be hoped that they are safe from risk, but in the event they have a build up of harmful exposure they should be placed on other duties with less exposure for a short period of time. When a crew runs into particularly bad weather and returns exhausted they are more likely to injure themselves on the next shift if they have not recovered in time. Rearranging their shifts will allow them time to recuperate on smoother water and get their energy back before tackling heavier seas.

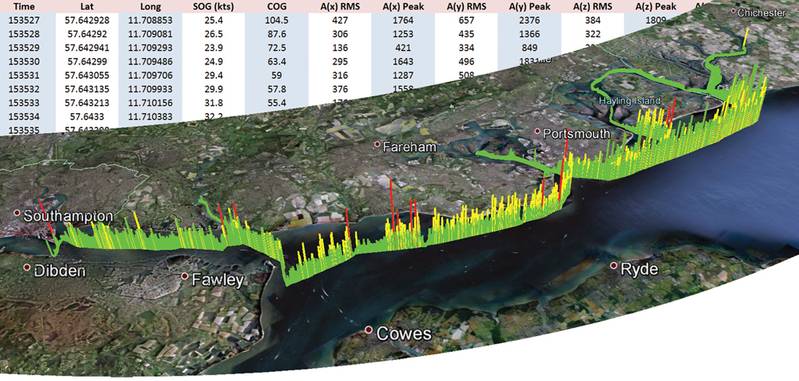

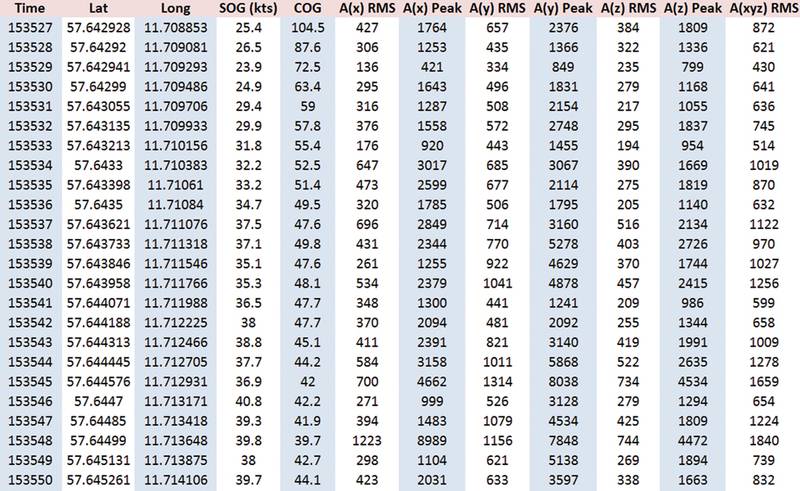

Monitoring does not require endless paper work. There are now systems available that will automatically record the impact exposure alongside the vessels position, filing the daily data in a user friendly format. A unit fitted to each vessel allows the Operations Manager to quickly and easily build up a database of the impact exposure the workers receive during different tasks. Over a period of time this can be used to alter their daily routine to ensure exposure is reduced. Implementing small changes can make a significant impact on employee’s long term health and maintaining this simple record will allow companies to prove they are engaging with the issues.

Shock mitigating equipment can reduce the crews exposure to damaging impacts. This includes suspension seating, shock absorbing flooring and personal equipment, but it is important to differentiate between comfort and protection. Soft cushions, rubber decks and a good pair of running shoes may improve the crews daily comfort but they won’t provide protection from spine damaging slams.

Seat or deck suspension systems need to match their intended environment. You wouldn’t expect the shock absorbers on a family car to be suitable for driving along gravel riverbeds; similarly some marine seating systems may be suitable for 25 knots in a coastal rib, but if your crews intend to chase across open water at 50 knots they are going to need a more robust system. As a simple rule, a suspension seat that ‘bottoms out’ is potentially more damaging than having a non-suspension seat.

Training can offer significant rewards. A single day spent in a group training event learning from other peoples experience can highlight areas where skippers could make improvements. For example, many of us have travelled by sitting on the tube of a rib, but we wouldn’t think twice about doing it again after seeing an x-ray of the damage that could be done if the boat were to fall into a single hollow unexpectedly.

A common mistake is to focus only on the skipper. In the marine industry there are often other passengers onboard. The skipper is in control and can better prepare themselves for impending impacts, but the passengers are often less aware of what is coming and may not be experienced seafarers practised at absorbing the bumps. As a result when they reach their destination they may be fatigued and less able to perform their required functions.

Duty of Care

An employer has the responsibility to protect its workers, overriding the employees enthusiasm if required. We would not let a young worker go to sea without a life jacket, even if they maintained that they were a champion swimmer, so why do we continue to let fast boat operators risk serious injury and turn a blind eye towards it?

Historically it has been shown that workers will resist acknowledging the dangers they face, leaving the employer to enforce safety practises until they become common practise. Examples include safety glasses in workshops, hard hats in construction sites and Kevlar clothing for chainsaw operators.

The most severe injuries, seen as a result of bad slamming events, include fractures to vertebrae or other extremities, and rupture of intervertebral discs in the spine and neck. These do not happen to everyone that steps aboard a boat, but neither is everyone in a car going to crash, yet we still wear seatbelts.

Advances in Data Collection

Monitoring the impact exposure is now more simple than many realize. Previously this required costly data logging equipment with accelerometers fitted to the boat, providing the user with raw data of the hull impacts and vibrations. Accelerations must be measured using a high sample rate requiring frequent downloading of the data due the large memory required to store the values. The daily processing of this data can take considerable time and requires experienced professionals to highlight potential impact exposure risks.

Data recorders designed specifically for monitoring the impact exposure of the vessel, crew and passengers are now available. The DaccR from Dyena measures accelerations simultaneously in 3 axes and performs all processing onboard alongside GPS data to provide accurate information in a user friendly format. The memory requirements are a fraction of standard data loggers and over 600 days use can be recorded before a data download is required.

This is the Future

An employer’s duty of care requires them to ensure that all passengers and crew are safe and it is in their interests to monitor the situation not only from a health and safety perspective, but also to expose any driving habits or situations that may be putting other staff at risk. A crew member or passenger with an injury caused by an overzealous or unlucky skipper could result in a financial loss for the company and a subsequent investigation by the relevant Safety Executive and insurers.

Now that impact exposure is an acknowledged danger and subject to legislation, employers are required to prove that their staff are not at risk, or that they have taken steps to reduce their impact exposure. Either a daily health questionnaire or an automatic impact exposure recorder is a cost effective first step before investing in more expensive shock mitigation equipment and provides a metric of before and after conditions.

With boats becoming faster and personnel resources reduced, there is even more pressure on professional marine operators to push the limits of their craft and crew. Unless they can invest in more boats and staff, the ability to monitor the health of their workers is paramount. Impact exposure and WBV are not going away and ignoring them will increase the chance of human injury or commercial liability. So it should be addressed now before it is too late.

(As published in the September 2013 edition of Marine News - www.marinelink.com)