Discovery: Historic Shipwreck Found in Lake Huron

Researchers from NOAA, the state of Michigan, and Ocean Exploration Trust discovered an intact shipwreck resting hundreds of feet below the surface of Lake Huron. Located within NOAA's Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary, the shipwreck has been identified as the sailing ship Ironton. Well preserved by the cold freshwater of the Great Lakes for over a century, the 191-ft. Ironton rests upright with its three masts still standing.

"Using this cutting-edge technology, we have not only located a pristine shipwreck lost for over a century, we are also learning more about one of our nation's most important natural resources—the Great Lakes. This research will help protect Lake Huron and its rich history," said Jeff Gray, Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary superintendent.

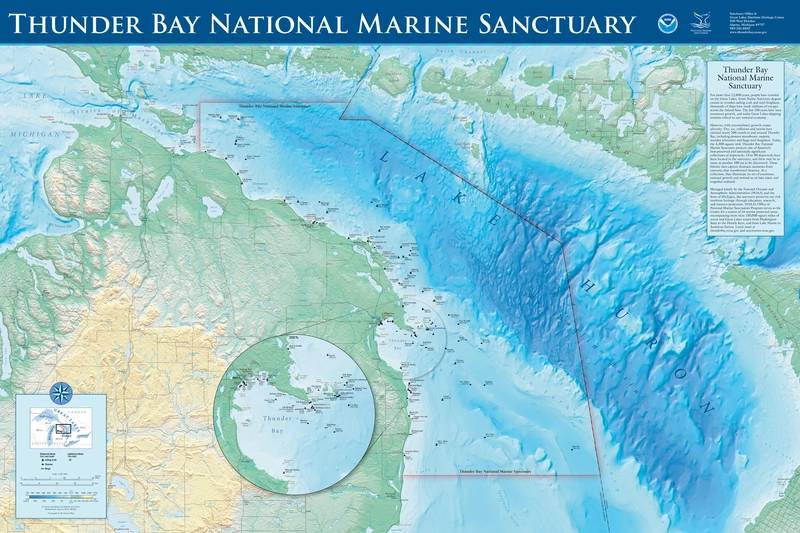

Location of NOAA’s Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary in Lake Huron. Image Credit: NOAA Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary

Location of NOAA’s Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary in Lake Huron. Image Credit: NOAA Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary

The Sinking

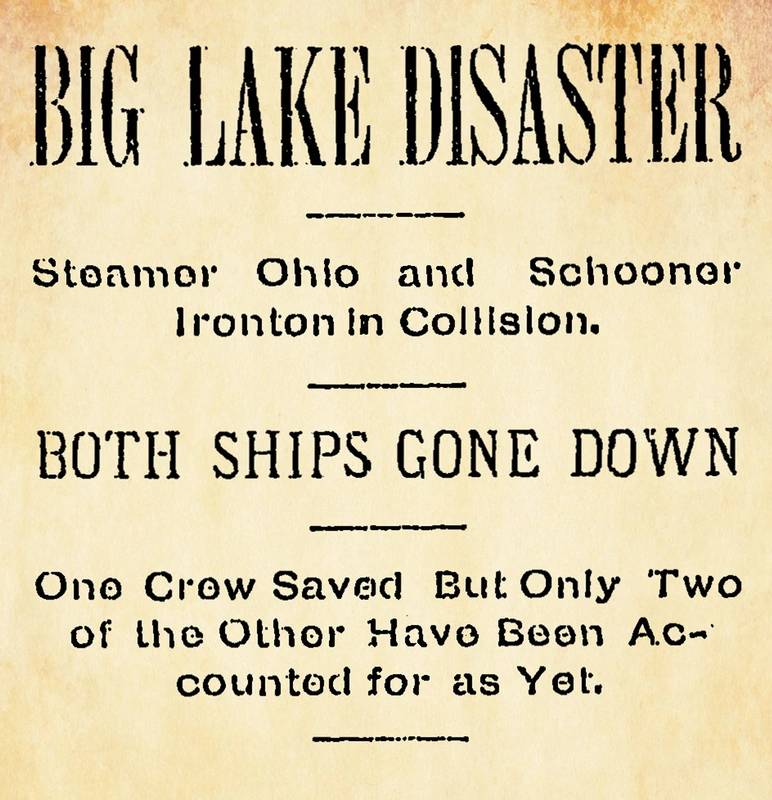

In September 1894, Ironton sank in a collision that took the lives of five of the ship's crew. Accounts from the wreck's two survivors provide details about the loss of the vessel in "Shipwreck Alley"—an area of Lake Huron known for its treacherous waters that have claimed the lives of many sailors.

The 190-foot steamer Charles J. Kershaw departed Ashtabula, Ohio, on Lake Erie, with the schooner barges Ironton and Moonlight in tow. The vessels sailed empty, destined for Marquette, Michigan, on Lake Superior.

At 12:30 a.m. on Sept. 26, while sailing north across Lake Huron under clear skies, Kershaw's engine failed, leaving the ship without power. A few miles north of the Presque Isle Lighthouse, a strong south wind pushed Moonlight and Ironton toward the disabled steamer. To avoid entanglement and a possible collision, Moonlight's crew cut Ironton's tow line, detaching the steamer from the schooner barges.

Ironton's crew found themselves suddenly adrift in the dark and at the mercy of Lake Huron's wind-blown seas. Under the direction of Captain Peter Girard, they fought to regain control of the ship, firing up the vessel's auxiliary steam engine to help set the struggling ship's sails. Despite their efforts, Ironton, propelled by the wind from astern, veered off course into the path of the southbound steamer Ohio. The 203-foot wooden freighter Ohio was headed to Ogdensburg, New York, from Duluth, Minnesota, loaded with 1,000 tons of grain.

By the time Ironton's crew spotted the approaching Ohio through the darkness, it was too late—a head-on collision with the steamer was unavoidable. In an interview published by the Duluth News Tribune the following day, William Wooley of Cleveland, Ohio, a surviving crew member of Ironton, recounted his experience.

- At this time we sighted a steamer on our starboard bow. She came up across our bow and we struck her on the quarter about aft of the boiler house. A light was lowered over our bow and we saw a hole in our port bow and our stem splintered. (Duluth News Tribune, Sept. 27, 1894)

News headline from Grand Rapids Press, September 26, 1894. Image courtesy Ocean Exploration Trust/NOAA.

News headline from Grand Rapids Press, September 26, 1894. Image courtesy Ocean Exploration Trust/NOAA.

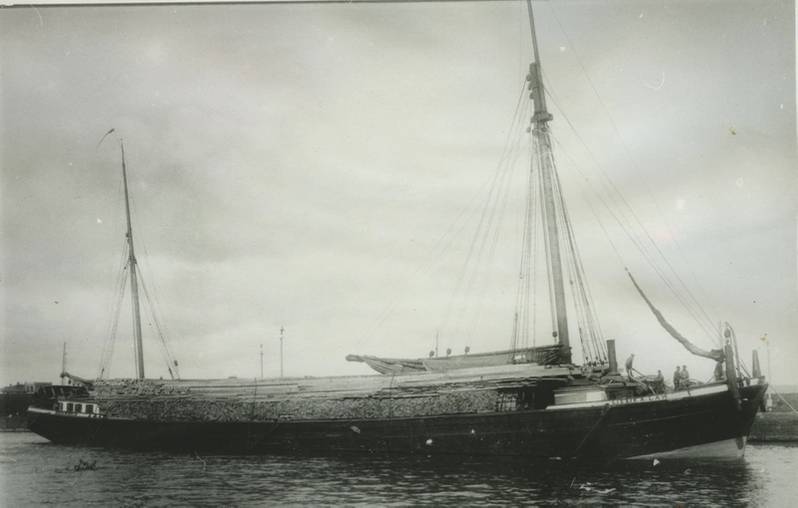

Historic image of the schooner barge Lizzie A. Law, built in 1875 of similar construction to Ironton. Image Credit: Thunder Bay Sanctuary Research Collection

Historic image of the schooner barge Lizzie A. Law, built in 1875 of similar construction to Ironton. Image Credit: Thunder Bay Sanctuary Research Collection

The two vessels separated after the impact, both fatally damaged. Ironton's bow tore a 12-foot diameter hole into Ohio's wooden hull. Heavily laden with cargo, Ohio sank quickly, with all 16 crew escaping on lifeboats. Nearby ships rescued the sailors. The damaged Ironton, however, drifted out of sight of the responding vessels. By the time Captain Girard realized he could not save the ship, Ironton had drifted for over an hour, far from the view of any surrounding vessels.

As the schooner barge slipped swiftly beneath the waves, Ironton's seven-man crew retreated to their lifeboat. However, in the commotion, no one untied the "painter," a line that secured the lifeboat to Ironton, as survivor William W. Parry of East China, Michigan, recounted: Then the Ironton sank, taking the yawl with her. As the painter was not untied, I sank underwater, and when I came up grabbed a sailor's bag. Wooley was a short distance from me on a box. I swam to where he was. (Duluth News Tribune, September 27, 1894)

Wooley and Parry clung to floating wreckage as they battled the wind and waves in frigid Lake Huron. Within hours the passing steamer Charles Hebard spotted and rescued the men. Lake Huron claimed Captain Girard and four other Ironton crew: Mate Ed Bostwick, Sailor John Pope, and two unidentified sailors.

Autonomous surface vessel (ASV) BEN pictured in the Rogers City Marina. Image Credit: Ocean Exploration Trust/NOAA Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary

Autonomous surface vessel (ASV) BEN pictured in the Rogers City Marina. Image Credit: Ocean Exploration Trust/NOAA Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary

Pilots from the University of New Hampshire’s Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping operate ASV BEN from the Mobile Lab in Rogers City, Michigan. Image Credit: Ocean Exploration Trust/NOAA Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary

QUOTABLE: Dr. Robert Ballard, President, Ocean Exploration Trust: “Our team is proud to partner with the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries to bring innovative technology and expedition expertise to map the Great Lakes,” said Ballard. “Ironton is yet another piece of the puzzle of Alpena's fascinating place in America’s history of trade and Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary continues to reveal lost chapters of maritime history. We look forward to continuing to explore sanctuaries and with our partners reveal the history found in the underwater world to inspire future generations."

A Piece of History

The three-masted Ironton represents the fleet of wooden schooner barges that once traversed the Great Lakes as the workhorses of the region's wheat, coal, corn, lumber, and iron ore trades. The Niagara River Transportation Company built Ironton in 1873 as a towed schooner barge.

Known as the "consort system," steamers towed one or several schooner barges and enabled companies to transport greater quantities of cargo across the Great Lakes at a lower cost. Either converted from older sailing vessels or purpose-built, schooner barges had masts and sails to save fuel in the towing steam vessel and in case of emergencies where they needed to sail independently. These iconic Great Lakes vessels were a link in the evolution of sail-powered shipping to mechanized transportation systems of the modern world.

Measuring 190 feet, 9 inches in length and 35 feet, 4 inches in breadth, the 772-ton Ironton boasted a carrying capacity of more than 48,500 bushels of grain or 1,250 tons of coal. During the ship's nearly 22-year career, Ironton changed ownership multiple times, transporting iron ore, grain, and coal between ports such as Buffalo, Cleveland, Marquette, and Duluth.

Finding Ohio

Although contemporary reports and eye-witness accounts describe the general area of Ironton's sinking, the exact location remained a mystery for more than 120 years. Researchers from NOAA's Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary, the state of Michigan, and Ocean Exploration Trust used cutting-edge oceanographic technology to discover and document the shipwreck.

In 2017, Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary and a group of partners led an expedition to survey 100 square miles of unmapped lakebed within the sanctuary. The team discovered the bulk carrier Ohio in approximately 300 feet of water. Despite the large area mapped, the location of Ironton remained a mystery.

In 2019, researchers from Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary set out on a mapping expedition in Lake Huron with Ocean Exploration Trust, the undersea exploration and education organization founded by famed explorer Dr. Robert Ballard, who has explored nearly every corner of the planet. Ocean Exploration Trust brought a team of world-renowned hydrographers and the latest innovation in underwater mapping technology to Michigan, including an autonomous surface vehicle named BEN (Bathymetric Explorer and Navigator).

"Our team is proud to partner with the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries to bring innovative technology and expedition expertise to map the Great Lakes," said Ballard. "Ironton is yet another piece of the puzzle of Alpena's fascinating place in America's history of trade and Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary continues to reveal lost chapters of maritime history. We look forward to continuing to explore sanctuaries and with our partners reveal the history found in the underwater world to inspire future generations."

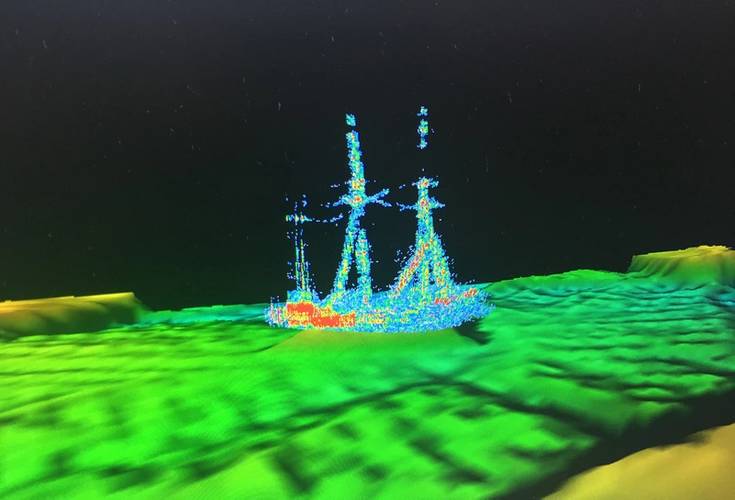

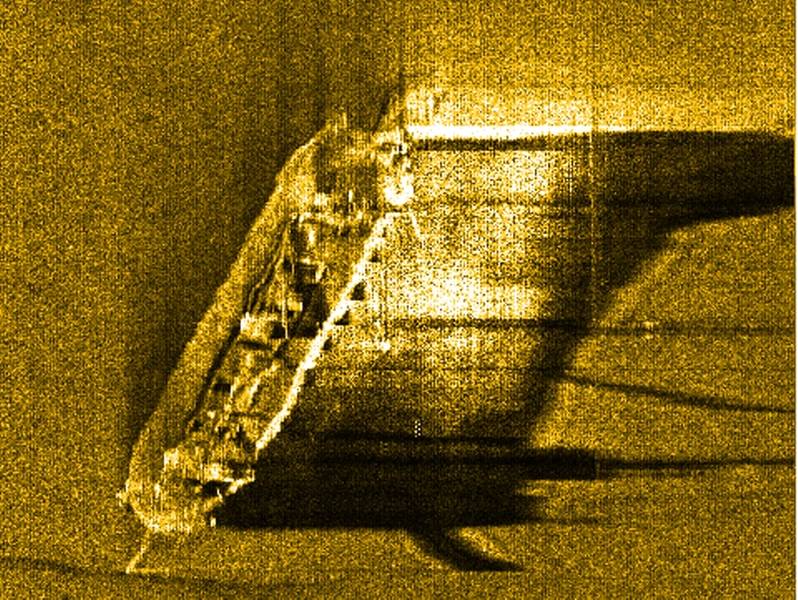

Sonar image of the Ironton. Image Credit: NOAA Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary

Sonar image of the Ironton. Image Credit: NOAA Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary

The Discovery of Ironton

Armed with the location of Ohio and further research into the weather and wind conditions from the night of the fatal collision, the team defined the area to search, and BEN and RV Storm worked in tandem mapping the lakebed.

As the project came to its final days, the team had successfully mapped a large section of the search area, but Ironton remained undiscovered. The researchers expanded the search area. Persistence and determination were rewarded when the sonar returned an image from the lakebed of an unmistakable shipwreck—and one that matched the description of Ironton. The sonar images provided great detail, but the team had more work to do in order to confirm the identity of the discovered wreck.

The following month, archaeologists from Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary teamed up with the Great Lakes Water Studies Institute at Northwestern Michigan College to explore the discovery. Using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) from aboard RV Storm, the team sought to confirm the ship's identity through video images. As the team excitedly watched the footage from the ROV, there was no mistake: Ironton had been found.

In June 2021, Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary and Ocean Exploration Trust returned to the site to carry out a more thorough investigation of Ironton. Conducting ROV operations aboard U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Mobile Bay, the research team partnered with the University of North Carolina's Undersea Vehicle Program to collect high-resolution video and further document the wreck. Resting upright and incredibly well preserved by Lake Huron's cold freshwater, Ironton looks almost ready to load cargo.

Project Partners

NOAA and the state of Michigan jointly manage Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. This project was made possible with the support of Ocean Exploration Trust and with technologies from the Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping, the Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory, the University of North Carolina's Undersea Vehicle Program, and the Great Lakes Water Studies Institute at Northwestern Michigan College. The documentation of the shipwreck Ironton would not have been possible without the dedication of the United States Coast Guard.

Stephanie Gandulla is the resource protection coordinator for NOAA's Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary Members from the June 2021 expedition team pose on board the USCGC Mobile Bay; the remotely-operated vehicle (ROV) sits ready for deployment on deck. Image Credit: Ocean Exploration Trust/NOAA Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary

Members from the June 2021 expedition team pose on board the USCGC Mobile Bay; the remotely-operated vehicle (ROV) sits ready for deployment on deck. Image Credit: Ocean Exploration Trust/NOAA Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary