Ship Design and Construction Software Solutions

Tech morphs design loft into loftier designs; Earlier decision making, modularity cut time and labor costs

From the design loft to loftier designs and better-built ships, software has changed the face, and build, of nautical vessels. The far-reaching impact of ship design and construction software on the marine industry cannot be overstated, especially in an era of increasing regulation, bigger, sometimes more complex ships, and razor-thin margins.

With shipyards and fleet owners alike, the end goal is the same – cutting costs without compromising safety and reliability. And to hear ship designers, owners, builders and vendors alike tell it, automation, much as it has been in other industries, is the key.

“Software has impacted the full spectrum of the maritime industry – design, construction and ship management. From the design side its primary benefit is to enable the ship designers to optimize ships both from the perspective of efficiency, and to optimize the weight, speed and power of the vessel as well as reliability and safety,” says R. Keith Michel, president of The Webb Institute, and former chairman of Herbert Engineering Corp., a provider of ship design and engineering services.

“I think software is crucial for any large-scale design or construction process. If a facility doesn’t adapt, it will be out of business,” says Prof. Richard Neilson, dean at The Webb Institute, in an opinion echoed by other across the nautical spectrum. “I haven’t seen a shipyard work without it. I think creating products of a size today like big cruise liners, is not possible without design and construction software,” adds Benjamin Mesing, a graphics researcher at German research institute Fraunhofer IGD.

“We’ve gone from piles of paper to doing it all on your computer,” agrees RDML Joe Carnevale (Ret), a senior defense advisor for Shipbuilders Council of America (SCA), a national trade association representing over 120 U.S. shipyard facilities. “Almost no one I know of is doing paper design. It’s All CAD in one form of another. Do all companies have a high-level of 3D CAD processing? No. Lots of companies don’t require 3D CAD. They are doing 2D drawings on the computer. The level of automation varies wildly, but AutoCAD is a standard in the industry. People pass around AutoCAD drawings all the time,” he adds.

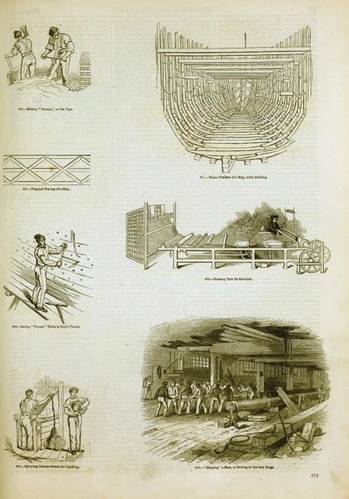

But in the beginning, there was paper. Oceans of it. Millions of paper drawings and huge pattern sheets laid out on the floors of enormous “lofting” rooms. Then came calculations run on expensive mainframes in the ‘70s, just as the industry was transitioning from slide rulers to calculators. The PC revolution in the early ‘80s brought affordable computer-aided design (CAD) to the desktop – initially in the form of the now ubiquitous AutoCAD. Naval architecture hasn’t been the same since.

Nor, actually, has the collection of related processes involved in the design and construction of ships – from the selection of materials and parts, to the supply chain, to purchasing, scheduling and every stage of manufacturing.

The Paperless Architect

“The old lofting room from back in the day? It’s now inside the computer,” says Darren Guillory, lofting designer at Leevac Shipyards, LLC, and a user of SSI’s Ship Constructor package. “I cannot imagine building a ship today without this type of software. It’s a godsend.”

“You can build a boat in a whole day on a computer; you can’t do that in real life,” elaborates Jim Hyslop, Manager, project development for Robert Allan, Ltd., the leading designers worldwide in the tugboat market. That’s a far cry from the old design chestnut recalled by Neilson, “Never draw more in the morning than you can erase in the afternoon.”

Moreover, “when you build the ship electronically – it’s a whole lot cheaper to move a linear box in a 3D model than it is to have to throw material out,” notes Jerry Pinkard, a Design Group vice president, at legendary Naval architects Gibbs & Cox, Inc.

It’s a whole lot cheaper on a lot of levels, not the least of which are the opportunities to push interferences and rework orders down to a bare minimum by finding, and solving, problems much earlier in the cycle.

Even better are the cost savings realized from repeatability and reusability. “The degree to which you can debug a design so that it is interference-free, and built successfully, and then reuse that same design or design element from project to project, is where you can really see some benefits. Repeatability and setting up your construction facility to build common parts that might be used on multiple different ship designs improves standardization and reduces costs. Lots of shipyards are moving in that direction,” observes Thomas A. Schubert, chief engineering officer also at Gibbs & Cox.

That repeatability starts with the creation and ongoing feeding of a library of common parts. It’s draw once, use twice - many times over. That capability delivers real economics by really shortening design time. It also helps cut production time as workers benefit from experience gained by working with the same part over multiple projects.

Evolution Leads to Revolution

While the growth in ship design and construction software functionality is seen as evolutionary, many of the changes left in their wake are nothing short of revolutionary.

One of the greatest advantages of design software is the ability to model multiple scenarios – what if we did this or that? In the past, a designer would have to make his bed and lie in it, essentially, by choosing an option and then committing to it. When the inevitable problems arose –it was further down the build sequence. That typically led to a raft of expensive and time-consuming rework orders. C’est la vie.

Not anymore. Today’s 3D design software automates the intent of another old naval architect saying: “On my honor I did my best, now let the checker do the rest!” Designers today do their own checking. They can test out online multiple possible solutions to a problem or design decision, or run virtual walk-throughs to make sure there are no obstructions, poorly located or inaccessible equipment or any other issue that might make it difficult to operate or maintain the ship. Catching these sorts of errors early in the design phase means a smoother production process, and consequently, savings in materials, time and labor.

Optimal Designs

Yet for many architects, automation isn’t so much about savings as is it about optimization.

“It’s always an optimization process when you balance safety and reliability against cost. Today, software has taken analysis to a much higher level than could in the past, enabling lighter, easier-to-build ships, which has brought the cost down,” says Michel.

“Design software allows you to really refine your design because you are able to look at more points and really optimize. In the past, you’d take an extremely conservative approach that you knew would work to get through the first pass of calculations, but you wouldn’t necessarily go back and refine them. Now you have the ability to look more closely at things,” adds Schubert of Gibbs & Cox.

Moreover, before modeling came in, shipyards had to prioritize what they spent their time on, and the most cost-advantage use of engineering in those days was lofting, according Joe Comer, principal and naval architect, Ship Architects, Inc.

“Foundation work was done in the field. If it wasn’t modeled, it didn’t have a home, and that meant it was up to the production guy to figure out where its home was. And depending on how good he was, it could be screwed.”

The placement of piping, conduits and ducts in a particular space was also often left somewhat up to production to duke it out over. Being first into a space to position your parts was a big deal, notes Carnevale. “God help if two guys come in at the same time. I have seen it come to fist fights,” adds shipyard veteran and Prof. Neilson.

Those days are gone, and with it, much of the potential for the introduction of interferences post the design walk-throughs. Shop floor drawings now come with all associated data attached to each object, including exact placement instructions. The result is tighter control over the way things are put together, and greater consistency in design follow through.

Getting to that level of accuracy starts with constant communication between the clients, the designer, procurement, scheduling, the “space king,” production and manufacturing.

“It’s given us the ability to work in geographically distributed areas, with everyone looking at the same model at the same time seeing the same views. It has allowed more participation from clients – more frequently along the way rather than at one or two points during the design process. You get multiple opinions, and can get all parties to agree on the path forward. Building that consensus during the early part of the design process is essential – as changes become more expensive as the design develops,” explains Schubert.

But, as representatives of different disciplines are able to spot and relay issues that would affect their piece of the build, corrections and adjustments are made earlier, and placement of ship elements are negotiated.

Bringing Production Into The Picture

And once the design is ready to go to production? It can be used to get shop floor buy-in to the entire project, not just their little corner of it

“The software lets you give the production team a better visual,” says Guillory. “Before, they had to see it in their own mind’s eye what they were working on. Now, you can have a production meeting with the yard people and give them a 3D virtual tour of the module or unit they are putting together. They can literally look at the boat they are working on before it gets built.”

Workers also get a 2D drawing with an assembly packet so they can see where each part goes and get a better understanding of the fitting of the part. Productivity goes up, man-hour costs go down. Construction software tools have also taken the guesswork out of a lot of things yard workers deal with, and in some cases, outright eliminated the need for some tasks. For example, when using a crane to place a large piece of equipment or modules, workers used to have to guess at the weight of the steel, count individual parts and guess their weight and calculate the center of gravity. Now, software tells them down to the individual part what something weighs. No more guessing and hoping for the best.

In another example, Leevac used to have a worker sit with a drawing and a booklet and physically measure where stiffener angle irons would go. Today, construction software does all that. “Now it will literally tell you in bundles “this many at this length” and what the end cuts are, part names, how much it weighs, and where it goes in the vessel. It completely takes out the middle man,” says Guillory. All these changes taken together have “unbelievably enhanced our ability to lower production time on more enhanced vessels,’ he adds.

Honey, I Shrunk the Crew

Design software can do more than eliminate a task here and there. It can significantly reduce the required number of crew, saving a substantial amount of money over the life of the vessel, says Alain Houard, vice president of Marine and Offshore, Dassault Systemes, maker of Catia design software and 3D and simulation applications. Shipyards, of course, are using automation and robotics to reduce head counts.

He cited as an example, a requirement by the U.S. Navy to reduce the crew onboard submarines and aircraft carriers. “Crew size was seen as a cost for the duration of the ship over 30 years. We saw aircraft carriers reduce by a factor of 2 the number of sailors on ship. So now you have 5,000 less people over 30 years.,” Houard says. Even in the cruise liner industry, where he estimates that you have roughly the same amount of passengers to crew, smaller reductions in personnel are possible.

These reductions are accomplished in part by starting each new project with the design mission and a list of requirements; “you don’t start with geometry,” says Houard. From there, he explains, the architect designs the minimal amount needed to support the requirements, such as how much steel would be needed or how many people to run the ship. “If you keep the requirements in sight, as you pursue design, you can keep the connection between the design activity and design requirements.”

Fishing out the Hidden ROI

Impressive crew reductions aside, while software is often evaluated in terms of its ROI, when it comes to maritime software – it’s not always immediately apparent.

“Early in the design phase” is the mantra in ship building today, and with good reason. But pushing as much decision-making, testing and data collection as possible as early as possible can actually lengthen this part of the process, potentially saving time down the line.

Ship design software, for example, doesn’t necessarily save time, and it’s probably better if it doesn’t. It can actually eat up more time on the front end because of the many avenues through which it enables ship architects to optimize their designs. Much of this revolves around doing more, earlier in the process: meeting more often with more people to collect more feedback to make detail decisions earlier and to embed more fully fleshed out data in the designs and work orders, to creating virtual walkthroughs to test options and root out obstructions and other interferences that could lead to production slowdowns and costly rework if not caught early on.

“I don’t believe we save in man hours re design versus 40 years ago. The benefit is that we go in-depth to a much greater extent with regard to the design. We do a lot more in the design process, which results in better ships,“ says Webb’s Michel.

From a time perspective, it doesn’t necessarily help shipyards build ships any faster either. What it does do, however, is enable the construction of more complex ships period, and in roughly the same timeframe as older, less sophisticated vessels.

And even that savings might not be immediately apparent in some cases. “The cost to build a more complex ship – the time to build is basically the same as to build a less complex model,” according to Fraunhofer’s Mesing. It doesn’t look like a savings, but it is, because more complexity usually means more time to build, and that’s not happening generally, thanks in large part to the processes enabled by today’s software.

“There are a lot of things that let a ship be built faster. The complexity of war ships has gone up so much it still takes as long or longer to build because they are far more complex than they used to be. But if you take into account the complexity increase, design and construction software does let them be built faster,” adds Carnevale.

The payoff is more evident in more common commercial projects. “I think the time saved to build the ship is the reward. Some people say they can save 30% in man hours. It takes a lot of man hours to manufacture ships. So if saving 30%, you are saving time and saving the customer money.” Comer said.

Those savings are greatly helped along by software’s ability to aid and enhance the build sequencing (what gets built in what order and in each section, what gets installed in what order) or work scheduling process, by enabling the supervisor to pull together all drawings and related data for each part of each module. In fact, some industry observers don’t think this process is possible with the aid of a computer.

Another avenue to achieving positive ROI is modularization. Prefabrication came about during WWII, of course, driven by the need to crank out Liberty ships as fast as possible. But many of the techniques developed during that period were not widely adopted after the war, for a variety of reasons. The arrival of desktop CAD and the growth of automated manufacturing, working hand-in-hand, has greatly facilitated the use of modular construction. Building pieces to a whole in different areas was always possible; fitting them together accurately was the real stumbling block. Stories abound of sections that were built and brought together with mismatched connections. One team thought left, the other right, in a case recalled by Carnevale. Oops.

But it takes an integrated system, an organized shop and the ability to work in tandem with many partners during the design process to cost-effectively build ships in a modular manner.

Challenges to Overcome

Modularity speaks to some of the bigger challenges facing shipyards: to get the most out of their design and construction software, they have to integrate it with their ERP, purchasing and manufacturing systems – no small feat. The challenge of ship building nowadays is to figure out how to set up a planning and production process routine that allows a scheduler or building sequencer to pull out and package all the data needed about each aspect of each section of the ship, and which coordinates with materials purchasing, outside suppliers, deliveries etc. If you don’t get this part right? You won’t get anything right, insists a 30-year veteran of naval contracting with shipyards. Adds Carnevale, “Nightmares were so widespread that ERP has become a four-letter word.”

But integrating these marine applications with the rest of the company’s systems – financial, purchasing and manufacturing – is critical to success. With so much data being embedded in the design so early in the process, providing that information to other departments allows parallel processes to take place. For example, purchasing can see at an earlier stage what materials are going to be needed, when they are needed and where they’ll be stored or used, and can start working on ordering. And because the design software can more precisely instruct cutting machines on dimensions, weight etc., there is less material waster.

The U.S. Navy, which floated the first completely cyber-built vessel when it launched the USS Virginia submarine, struggled with culture and ERP-level systems integration.

“When you have being doing something or 2,000 years, you do get stuck in your ways. There are people in the Pentagon who think [ancient Greek mathematician and engineer] Archimedes is working for some Naval Command [group]and he can be ignored.” jokes Carnevale

Push to Open Up Software

Complicating this part of the process is the issue of open software: Much of the industry’s applications are proprietary, which makes trying to exchange or extract data between two different packages cumbersome to impossible, and often in unexpected ways. There was the time, for example, when Ingalls and Bath Iron Works needed to exchange data – the problem was one set of data was generated out of Cartesian coordinates while the other was based on Polar coordinates. Mathematical routines enabled the two sets of data to work together – but with a loss of some accuracy – enough to drive people crazy.

“The challenge today is that the more intelligence you put into a model, the harder it is to exchange with some other system. Some level of data can be transferred, but not all of it,” explains Gibbs & Cox’s Pinkard. The lack of openness is a major source of frustration in the industry and not likely to abate anytime soon, which forces shipyards to write some of their own interfaces to the packages they need to talk to.

A Little of that Human Touch

While the software significantly cuts down on the introduction of human error, one thing it is no match for, is human experience and intuition.

Greater degrees of automation means that “You don’t have that human error inserted every time you go from a drawing to material, to tech manuals to maintenance,” says Carnevale. He tells a story of a project involving a mixed gas diving system that required specialized fittings, valves and connectors – all special orders with long lead times. In particular there were six elbows in the piping system. Once his team, got to the point of installing the parts, it turned out that in several cases, the materials list did not match the number of fittings required, thanks to human error that was never caught. “It delayed us – it had a major impact. Simple things like that can be eliminated by a computer system. When a computer system counts, it does not fail to count.”

CAD also tackles human error by allowing the design to embed all the information associated with an object into a drawing of it. It’s the first step in translating an architectural drawing into a material ordering process.

However, software is still no substitute for human innovation, “says Fraunhofer’s Mesing. “Experience is still a very important factor. Even if you have a good solution today, an inexperienced architect can’t create a ship for you. There is a lot of intuition involved in where to put modules, for example, and the flow of things, that can’t be automated.”

Back to the Future

There is a lot on tap for the future. Regardless of software application – design, construction, fleet management or operations – the path is clear. What designers, shipyards and fleet owners want, what they and analysts say are needed, is integration, mobile devices on the production floor, simulation and tools to make better use of the collected data.

Look for integration on multiple levels. Much of the software available today is all or partially proprietary. There may be an Autocad link at some point, but the lack of open protocol support is a major headache. Reusability is a key concept in cutting shipbuilding costs, so no one wants to have to rely in data that won’t transfer over, or be forced to print it out on the paper they are trying to leave behind.

They also want to be able to pull in and analyze information from multiple sources in order to optimize as much as possible their ship designs and eliminate as much as possible mistakes at any point in the supply chain and manufacturing process. Rework is lost dollars, plain and simple.

Paper is still big on the shop floor. The way to get away from it is to equip workers with mobile devices that they can download job assignments to – complete with 3D images and assembly information packets – and in some cases, point their devices at objects or processes and either launch an activity or get more in-depth ta. No more running over to the paper board and double checking measurements.

It’s not as expensive as you might think – business analysts are already talking about a crash in the tablet market as cell phone makers move to absorb more features into their smart phones, which in turn, will drive down hand-held device costs. It’s also closer than you might think. According to Dassault’s Houard, Japanese ship yards are already deploying mobile devices for production work. Users can expect to see greater use of cloud computing and 3D, even 4D modeling is coming down the pike.

Between the capabilities currently available, and the wave of new functionality building up down the road, ship designers and builders that are committed to automation can look forward to even greater cost and time savings – and without compromising the tenets of safe sailing,

(As published in the August 2014 edition of Maritime Reporter & Engineering News - http://magazines.marinelink.com/Magazines/MaritimeReporter)

![“When you have being doing something or 2,000 years, you do get stuck in your ways. There are people in the Pentagon who think [ancient Greek mathematician and engineer] Archimedes is working for some Naval Command [group]and he can be ignored.” RDML Joe Carnevale (Ret), Senior Defense Advisor, Shipbuilders Council Of America](https://images.marinelink.com/images/maritime/w80h50pad/being-doing-32956.jpg)

![“When you have being doing something or 2,000 years, you do get stuck in your ways. There are people in the Pentagon who think [ancient Greek mathematician and engineer] Archimedes is working for some Naval Command [group]and he can be ignored.” RDML Joe Carnevale (Ret), Senior Defense Advisor, Shipbuilders Council Of America](https://images.marinelink.com/images/maritime/w800h500/being-doing-32956.jpg)