Securing the Deep: Business Opportunities in Subsea Defense

As global reliance on subsea infrastructure grows, so do the risks. Discover how safeguarding undersea assets opens new frontiers for innovation and investment.

Importance of Subsea Infrastructure

Subsea infrastructure plays a critical role in maintaining the operational continuity of the modern society and the global economy. This vast network includes subsea data and communication cables, pipelines for energy transportation, electricity cables, and resource extraction systems. What’s important is that these components are increasingly vulnerable to damage, whether due to natural phenomena or intentional human interference.

In the realm of communications, submarine cables are indispensable:

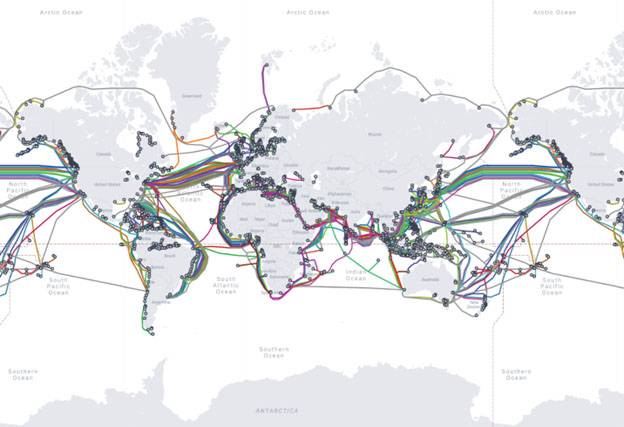

- They carry between 97% to 99% of global internet traffic, underpinning everything from everyday civilian internet usage to critical financial transactions and military communications (Defense News, 2020; TeleGeography, 2024).

- Cable traffic represents about $10 trillion in daily financial transactions. (Defense News, 2020)

- With over 570 submarine data and communication cables currently in use, stretching across more than 14 million kilometers and connecting over 1,300 landing stations globally, these cables form the backbone of our global connectivity (Military Law Review, 2021; TeleGeography, 2024).

- As of June 2024, this number has grown to include more than 600 active and planned submarine cables, emphasizing their continued expansion and importance (TeleGeography, 2024).

Map of Submarine Cables. Credit: TeleGeography

Map of Submarine Cables. Credit: TeleGeography

Beyond communication, the seabed also supports extensive energy infrastructure, including gas pipelines and electricity cables. For example, the North Sea alone hosts approximately 3,000 kilometers of gas pipelines alongside numerous cables1. As climate change accelerates the shift to renewable energy, the importance of undersea infrastructure has significantly increased. While some traditional oil and gas pipelines may decline in number, there are initiatives to repurpose these structures for new applications, such as transporting hydrogen or enabling carbon capture and storage. Additionally, electricity cables interconnect power markets, allowing for electricity transfer to balance supply and demand across regions and between islands and the mainland, thus supporting the integration of variable renewable energy sources. The growth of offshore wind power, for instance, requires more seabed electricity cables to connect new wind farms to the grid.

Aside from civilian uses, underwater cables are vital for military operations. Most military communications, including those necessary for operating remote drones in distant theaters, are transmitted through the transatlantic and transpacific cable networks. These cables also facilitate secure military-encrypted and diplomatic communications, underscoring their strategic importance (Wilson Center, Polar Institute, 2024).

In today's competitive and threat-laden environment, the vulnerabilities of our expanding subsea data and energy transportation systems—responsible for transferring molecules and electrons—are increasingly exposed. This highlights the critical importance of subsea defense.

Vulnerabilities and Attack Vectors

Subsea infrastructure, while critical, is fraught with vulnerabilities that pose significant risks to global security and economic stability.

Physical Vulnerabilities

Subsea security and seabed warfare have become prominent issues in the context of gray zone operations and sub-threshold warfare against critical underwater infrastructure (CUI). For hostile state actors, disrupting CUI is an attractive strategy due to its low-cost, high-impact potential, driven by critical dependencies and the cascading effects disruptions can have (Wilson Center, Polar Institute, 2024). Among CUI, fiber optic data and communication cables are particularly susceptible to disruption. The Arctic region exemplifies this vulnerability due to its geographic and natural chokepoints, like the Svalbard, Greenland–Iceland–UK (GIUK), and Greenland–Iceland–Norway (GIN) gaps and the Bering Strait, where cable resilience is minimal. This lack of redundancy, along with increasing geopolitical importance of the Arctic, makes cables in the region prime targets for seabed warfare (Wilson Center, Polar Institute, 2024).

While, in most places, cables are widespread across the ocean floor, reducing bottleneck risks, their landing stations can become focal points for potential attacks due to their geographical concentration (Kavanagh, 2023). Coordinated attacks on critical nodes could cause cascading failures, significantly affecting systems and escalating costs, with broader economic and societal repercussions (Rand, 2024).

Practically speaking, in deeper waters, cables lie unprotected on the seabed, making them less vulnerable to anchoring or trawling but more susceptible to deliberate sabotage. Additionally, the public availability of detailed maps displaying cable locations increases their exposure to malicious acts (TeleGeography).

Attack Vectors

One of the key vulnerabilities of subsea infrastructure lies in its geographical isolation. The lack of an immediate human presence at these sites makes physical threats, such as attacks on fiber optic and copper cables, relatively easy to execute (Turing Institute, CETAS). This remoteness also results in longer response times for security services, further compounding the risk.

The rise of autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) and drones has introduced a new dimension of threats. These technologies can be exploited for hostile surveillance or direct attacks. Additionally, as drone-based operations and maintenance (O&M) become more common, the risk of hacking or malware implantation during production grows. Such vulnerabilities could allow malicious actors to manipulate drones once they are operational (The Diplomat, 2023). These advancements not only enhance the capabilities of state actors but also extend sophisticated tools to terrorist organizations and criminal networks, broadening the scope of potential threats.

The subsea cable industry also faces critical supply chain risks. China's rapid emergence as a leading subsea cable supplier, driven by its Digital Silk Road initiative, has positioned it to capture a significant share of the global fiber-optic market. Companies like HMN Technologies, which supplied up to 18% of subsea cables between in 2019-2023, play a major role in expanding global cable infrastructure (Reuters, 2023a). However, this dominance raises national security concerns, particularly among NATO members (CSIS, 2024). Firmware and software used in cable landing stations could be compromised before installation, with adversaries potentially embedding bugs or surveillance devices in hardware. Once breached, attackers could manipulate cable controls or disrupt operations.

While a single attack on subsea infrastructure might cause limited disruption, coordinated assaults could trigger devastating cascading effects—potentially serving as precursors to larger military actions or coercive strategies. Protecting this critical infrastructure is essential, requiring robust surveillance measures and international collaboration to address these growing vulnerabilities.

Recent Examples of Threats

In recent years, several incidents have highlighted the vulnerabilities of subsea infrastructure. In 2023, Taiwanese authorities accused Chinese vessels of cutting submarine cables that are critical for internet connectivity to Taiwan’s Matsu Islands (CSIS, 2024). The incident left 14,000 residents in digital isolation for six weeks.

In the Baltic Sea, a telecom cable linking Sweden and Estonia was damaged alongside a Finnish-Estonian pipeline and cable in October 2023, with investigations pointing to Russian and Chinese vessels as potential saboteurs (Reuters, 2023b). Further incidents in November 2024 saw communication cables between Sweden and Lithuania, and Germany and Finland severed, raising suspicions of sabotage (Guardian, 2024).

Globally, the South China Sea and the Red Sea have been identified as chokepoints for undersea cables. In March 2024, several major cables in the Red Sea were cut, impacting 25% of data traffic between Asia and Europe (Rand, 2024).

These threats are not just isolated incidents but may form part of broader strategic maneuvers. At the onset of potential hostilities, cable disruptions can serve as tactical enablers, preparing the battlespace for larger military operations. Such disruptions often occur alongside coordinated activities, marking the "first salvo" in broader conflict strategies (Wilson Center, Polar Institute, 2024).

Threats to Subsea Infrastructure

Subsea infrastructure is increasingly threatened by activities that fall within the realm of plausibly deniable, sub-threshold operations. These threats are often carried out by state and non-state actors using dedicated units, structures, and subsurface capabilities.

There are two primary categories of seabed warfare activities that adversaries might conduct against underwater cables: intelligence gathering and physical destruction.

- Intelligence Gathering

This involves mapping and monitoring seabed infrastructure, primarily conducted by civilian vessels and uncrewed underwater vehicles equipped with remote-sensing capabilities (Wilson Center, Polar Institute, 2024). Such operations allow actors to prepare for potential acts of sabotage and gain awareness of the cable layout. The physical tapping of cables to intercept communications, although technically challenging, is another form of intelligence gathering.

- Physical Destruction

This more direct form of attack involves severing cables or using undersea explosives like torpedoes or maritime improvised explosive devices (MIEDs) to damage or destroy them (Wilson Center, Polar Institute, 2024). Such actions can be disguised as accidental, using "ghost ships" to conduct anchoring and dredging activities.

Knifefish is a medium-class mine countermeasure UUV designed for deployment off the Littoral Combat Ship. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Brian M. Brooks/RELEASED

Knifefish is a medium-class mine countermeasure UUV designed for deployment off the Littoral Combat Ship. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Brian M. Brooks/RELEASED

Defense of Subsea Infrastructure

Given its critical role, the protection of subsea infrastructure presents numerous business opportunities, spanning challenges across sea, land, and cyberspace and in various sectors, including cables, landing stations, and repair ships. Entrepreneurs should recognize the critical role of these infrastructures and prioritize their defense as a vital component of national security, opening avenues for innovation and investment.

International and Regional Partnerships

In December 2023, a multinational effort named SeaSEC was initiated by the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, Finland, Norway, and Sweden. This program seeks to develop advanced methods for monitoring underwater infrastructure in the North and Baltic Seas, focusing on pipelines, wind turbine platforms, and internet cables1.

In April 2024, countries bordering the North Sea—including Belgium, Germany, Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, and the UK—agreed to work together on enhancing security for subsea energy and telecommunications infrastructure. This was quickly followed by a similar agreement among eight Baltic Sea nations to protect offshore energy assets.

On a broader level, there is an ongoing debate on whether CUI should be recognized as an operational domain of warfare (Wilson Center, Polar Institute, 2024). This could potentially lead to CUI being declared an official operational domain, enabling more comprehensive legal and military protection strategies.

As of now, the European Union (EU)'s Critical Entities Directive requires member states to enact protective measures for critical infrastructure, reflecting a coordinated effort across Europe (Rand, 2024). The collaboration between the EU and NATO also aims at improving the resilience of critical infrastructure. The EU-NATO Task Force has recommended further cooperation in monitoring and safeguarding maritime assets, resulting in initiatives such as the NATO Critical Undersea Infrastructure Coordination Cell in Brussels and a Maritime Centre for Security in London (Rand, 2024).

Public-Private Collaborations

By working with private companies, governments can better identify and protect critical elements of these systems. For example, RAND suggests establishing an international undersea infrastructure protection corps to combine public and private resources in safeguarding subsea assets (Rand, 2024).

In Germany, various stakeholders, including the German Navy, Federal Police, and Federal Maritime and Hydrographic Agency, are contributing their expertise to ensure the success of initiatives aimed at protecting subsea infrastructure. North.io, a German company focusing on organization and management of geospatial data with the help of AI, leads the effort2.

Germany's Argus project, supported by the Federal Ministry of Digital and Transport, further aims to utilize big data and AI technologies to protect critical underwater infrastructure. This €3.5 million initiative involves collaboration with the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre and focuses on developing autonomous systems for enhanced monitoring1.

Technological Solutions

The protection of subsea infrastructure relies heavily on advanced technological innovations that enhance detection, inspection, and response capabilities. The sheer volume of data generated by the automatic generation system (AIS) signals, port calls, and ship-to-ship meetings presents a challenge in filtering out critical threats from the noise (Windward, 2024a). In addition, malicious actors may manipulate data to obscure their activities. Detecting such deceptive practices and decoding data becomes necessary to ensure reliable maritime domain awareness.

Detection and Inspection Technologies

Remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and AUVs are essential tools for identifying unauthorized objects like surveillance devices or explosives that might be attached to subsea infrastructure. These vehicles are supported by customized launch and recovery systems, which ensure their safe and effective deployment (Royal IHC). They also employ sensors to detect potential threats, enhancing situational awareness.

For monitoring underwater installations such as cables and pipelines, ROVs, AUVs, and towed systems are equipped with advanced launch and recovery systems (LARS), enabling precise control during operations (Royal IHC). These inspection systems are complemented by hydrographic surveying tools, which use sonar for accurate seabed images to plan and execute detailed operational strategies.

The offshore energy sector offers valuable synergies, as demonstrated by the UK defense ministry's acquisition of the Topaz Tangaroa, a former subsea construction vessel (OEDigital, 2023). After military modifications, this 98-meter vessel will protect subsea cables and oil and gas pipelines. It will function as a “mother ship,” deploying remote and autonomous systems for underwater surveillance and seabed warfare.

Big Data and AI Innovations

The Germany Argus project will utilize the TrueOcean platform to analyze large volumes of underwater sensor data, providing a comprehensive situational picture that enhances threat detection and response capabilities2. By integrating underwater data, Argus improves risk identification, cross-references anomalies with critical infrastructure locations, and reduces response times. The project is also developing systems for automated monitoring and strategic decision-making in infrastructure security.

Data-Driven Proactive and Reactive Measures

By analyzing extensive maritime activity records, machine learning algorithms help identify potential threats and inform the strategic placement of infrastructure3. This proactive measure involves avoiding high-traffic maritime corridors to minimize risks, thus ensuring the safety of critical assets.

Advanced real-time tracking systems provide a comprehensive view of vessel movements, distinguishing between normal and potentially threatening behaviors3. Predictive behavioral analysis helps move beyond well-known threats to uncover new and emerging risks or the unseen threats. By building detailed vessel profiles and applying risk models, this approach identifies vessels more likely to engage in illicit activities and ensures that only relevant alerts are issued, facilitating timely and appropriate responses to potential threats. (Windward, 2024b).

Further, innovative tools for incident management and reporting enable incident replay and analysis, aiding in understanding events like near-misses or groundings3. This not only assists in liability and insurance claims but also enhances future safety measures.

Strategic Diversification

One of the key preventative strategies involves rerouting planned subsea cable systems away from hostile territories and vulnerable areas. This approach minimizes the risks associated with geopolitical tensions and reduces the potential for infrastructure vulnerabilities.

Further, to mitigate risks associated with overreliance on specific suppliers, there is an emphasis on diversifying trusted suppliers for technology and operations as well as ensuring that cable maintenance is performed by reliable vendors.

In addition, through enhancing network redundancies and interconnectivity, the subsea infrastructure becomes more resilient to disruptions. This involves creating multiple pathways for data and energy flows, allowing for alternative routes in case of an outage or attack. To note, however, is that interconnectors might increase vulnerability since they create more points of attack.

Several new projects in the North Sea and Baltic Sea are exemplary in integrating clean energy, redundancy, and interconnectivity. The TritonLink, for instance, plans to connect high-voltage grids in Belgium and Denmark via two energy islands in the North Sea, thereby supporting the EU’s transition to renewable energ2. Similarly, the Bornholm Energy Island (BEI) project between Denmark and Germany aims to integrate at least 3 GW of offshore wind power into the grid by the early 2030s. Another project, the Elwind initiative, seeks to enhance cross-border electricity connectivity between Estonia and Latvia.

In April 2024, the Viking Link project, celebrated as the world’s largest interconnector, officially launched, creating a vital energy link between the UK and Denmark to enhance energy security and grid stability2. Similarly, ambitious projects like the $3.2 billion Eastern Green Link 1 (EGL1) and the $5 billion Eastern Green Link 2 (EGL2) are set to strengthen electricity transmission across regions. Adding to these efforts, the proposed 6 GW North Atlantic Transmission One–Link (NATO-L) aims to establish a high-voltage direct current (HVDC) connection between North America and Western Europe, providing Europe with a more secure and carbon-free power supply.

About the Author: About the Author: Alisa Reiner is a second-year Master of Environmental Management student at Yale, specializes in energy geopolitics, markets, and security, with experience in energy research and consulting.

About the Author: About the Author: Alisa Reiner is a second-year Master of Environmental Management student at Yale, specializes in energy geopolitics, markets, and security, with experience in energy research and consulting.

References:

Defense News, 2020 •TeleGeography, 2024 •Military Law Review, 2021 •TeleGeography •Wilson Center, Polar Institute, 2024 •Kavanagh, 2023 •Rand, 2024 •Turing Institute, CETAS •The Diplomat, 2023 •Reuters, 2023a •CSIS, 2024 •Reuters, 2023b •Guardian, 2024 •Windward, 2024a •Windward, 024b •Royal IHC •OEDigital, 2023 •Gatehouse Maritime

Additional References