Waiting for the Windfall

The momentum for wind power continues to gather on the domestic waterfront. U.S. boatbuilders anxiously await the coming gale.

"In a few instances, the Customs and Border Protection Agency (CBP), charged with administrating Jones Act applicability, has ruled that foreign vessels may engage in equipment installations on the Outer Continental Shelf. CBP could also determine that driving a pole into the sea bed constitutes a point in the U.S., therefore upholding Jones Act authority for point to point commerce. In the end, farm developers may build U.S. vessels or turn to MARAD seeking exemptions. That said; it is apparent that the Jones Act will apply to all support and supply vessels."

The formation of the U.S. offshore wind farm industry is a lot like the wind itself. You can see things stirring and hear a rustling commotion, but if you are looking for something tangible and physical it’s just not there. We’ve all been told it is coming and have been waiting patiently. We’ve seen the successes in Europe and the forecasts for America look promising if the fairy tale can only turn the corner toward reality. In fact, the U.S. commercial marine industry could be blown away by the economic thrust of a new offshore wind market. The windfall could come in the form of higher day rates for tugs, supply vessels, cable laying vessels, and jack-up barges; as well as plenty of orders for new construction purpose-built work boats.

So what’s been the hold up? Offshore wind is a ‘green’ initiative and green always means go. Creating a new industry from scratch is no easy task. During the past twelve years, we’ve been waiting on the power consortiums to form their plans, the U.S. Government to create leasable plats, and for impact studies to be complete. Of course, all the stakeholders also get to have their say inclusive of the ocean freight lines, fishermen, beachfront hotels, air traffic controllers, the military, and even the voices of the whales and birds surely gets an ear. Finally, with the hashing out nearly complete, the constituents are coming together, leases are being let and the probability of blades buzzing at sea seems to be drawing near.

Keeping up with the Joneses

While the Merchant Marine Act of 1920 still remains a topic for political debate, it continues to provide a great shadow that American boat builders and U.S. flagged fleet owners love to seek refuge behind. This shadow has cast somewhat of a gray area when it comes to applicability for installing U.S. offshore wind farms located in the Outer Continental Shelf. The installation process requires some unique and extreme vessel specifications which only a handful of U.S. flagged vessels can currently meet. The stringent requirements have persuaded Europeans to construct purpose built installation vessels. If available for hire, these European installation vessels could be allowed to assist in the U.S. farm installations, perhaps even accelerating the process.

In a few instances, the Customs and Border Protection Agency (CBP), charged with administrating Jones Act applicability, has ruled that foreign vessels may engage in equipment installations on the Outer Continental Shelf. CBP could also determine that driving a pole into the sea bed constitutes a point in the U.S., therefore upholding Jones Act authority for point to point commerce. In the end, farm developers may build U.S. vessels or turn to MARAD seeking exemptions. That said; it is apparent that the Jones Act will apply to all support and supply vessels.

Brace for Impact:

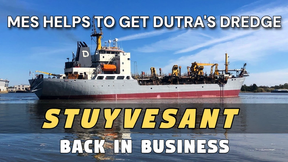

If we look to the lessons learned from European wind farms, the picture is clear that it will take many workboats to not only get the U.S. farms up and running but these craft must also remain exclusively available for repair and maintenance. Fleet owners, builders, and suppliers are all bound to benefit from a piece of the wind farm workboat pie. The first two projects likely to come online, Cape Wind and Bluewater Wind Delaware, are planning to install 130 and 150 turbines respectively. Right on their heels is Deepwater Wind which is recently the apparent successful bidder on two plots of sea floor located off the coast of Massachusetts and Rhode Island that have the potential capacity for 500 to 600 turbines.

Not to sound like a bad riddle, but how many workboats does it take to create an offshore wind farm? The boat builder’s rhetorical answer is always “it depends.” Each wind farm installation can vary from farm to farm depending on what type of foundation is selected: monopile, jacketed/tripod, or tethered and what type of installation vessel will be used. The varying foundations will affect how much work is performed on site and the materials needed. The distance from the port of supply and installation location will also influence the number and types of installation vessels needed. Preliminary indications from the developers indicate that both monopile and jacketed installations will be used and multiple options for installation vessel designs are being considered.

When will the farms start putting our work boats to work? In a nearly covert fashion, workboats are slowly being employed in anticipation of the wind farms. Buoy tenders have been deploying weather buoys and wind anemometers, hydrographic survey vessels have been mapping the sea floor, and geophysical research vessels have been analyzing the substrate. Wildlife researchers have also been out studying the impacts each farm location may have on the avifauna. The fleet will really get called to action once the first piece of steel is ready to hit the sand. On average, it will take 4 days to install each monopile plus an additional 4 days to set each tower and turbine into place. Once the turbines are in place, it takes nearly 1 full day per km to run connecting array cables.

The number of support vessels for installation will depend on the type of installation vessel employed. Towed Jack up barges will certainly need tug assistance as well as support from 3 to 4 crew and supply vessels. If a self-propelled installation vessel is employed, there is still a possible need for tugs and barges depending on hauling capacity. 3 to 4 crew and supply vessels will still be required. Once commissioned, approximately one support vessel will be required for every 20 to 30 turbines. By 2023, Germanischer Lloyd has estimated that 300 to 500 wind farm support vessels will be needed for Europe alone.

Blown out of Proportion

European insights are also giving rise to a new era of wind farm vessel technology. The installation vessel designs are getting larger and more sophisticated in an effort to reduce on site assembly time and cost. The trend is for a single vessel to transport fully assembled towers or carry sub-assemblies inclusive of tower, nacelle, hub, and blades for 6 to 8 complete turbines. Likewise, the maintenance support vessels are also taking on a new dimension with an increased focus on safety and seakeeping ability. These vessels, almost exclusively catamarans, are the back bone of the offshore wind farm and where investments will be made specifically for long term benefit over construction cost. For example, it is too costly to pay for technicians who arrive on the site fatigued or suffering from sea sickness and cannot perform their repairs.

IncatCrowther, BMT Nigel Gee, Teknicraft, Austal, and Damen have all proposed a variety of configurations with unique attributes for keeping the crew comfortable and safely getting crew and supplies to the platforms. The designs have slowly been growing in size too, starting at 49’ to now over 85’. IncatCrowther’s latest design for Supacat features a pass through cargo bay in which containers with supplies can be loaded, unloaded, or moved between either the fore or aft deck. Repositionable cranes, resiliently mounted cabins, and gps/gyro stabilized crew transfer platforms are also being fit on the newest vessels to ensure the job gets done and safety is ensured.

If the momentum continues, U.S. builders will soon be constructing their own state-of-the-art wind farm work boats. With a robust workboat building boom already in progress, the only question left to answer is when it will all start to happen. When it does, a re-tooled and well trained domestic boatbuilding force will be ready to make it happen.

(As published in the September 2013 edition of Marine News - www.marinelink.com)