US Plugs in First Large Offshore Wind Farm as Developers Play Catch-up

The U.S. offshore wind industry reached an important milestone on January 2 when Vineyard Wind 1, the country’s first large scale project, supplied first power to the Massachusetts grid.

“As the nation’s first utility-scale offshore wind farm this is a fairly momentous event,” Ken Kimmell, Chief Development Officer for Avangrid, the Iberdrola subsidiary co-developing the project with Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners (CIP), told Reuters Events.

The turbine will be joined by 61 additional turbines to provide 806 MW of power to the grid by the end of the year, enough to power 400,000 homes and businesses, Vineyard Wind CEO Klaus Moeller said.

“Six out of 62 turbines are complete and they are all connected to cables and ready to go when they have approval,” Moeller said.

The turbine connection is welcome news for U.S. offshore wind after a turbulent year. Rising costs, supply chain delays and high interest rates prompted developers to cancel offtake contracts agreed with East Coast states, delay projects and write down billions of dollars of investments.

Vineyard Wind benefited from an earlier start, minimizing the impact of rising costs, after receiving final federal approval in May 2021.

However, the developer had to overcome challenges associated with developing the U.S.' first large-scale offshore wind array. A lack of U.S. installation vessels, and service infrastructure created logistics challenges and the developer had to overcome first-of-a-kind challenges for environmental approval.

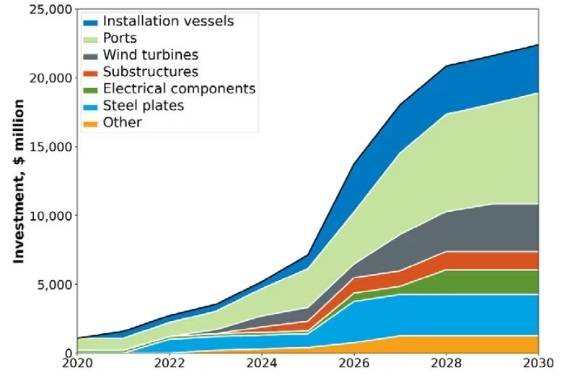

Learnings gleaned by Vineyard Wind will aid other developers and tax credits in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act will boost the economics of future projects but the U.S. must accelerate infrastructure investments and regulatory changes in order to meet the 30 GW offshore wind target set by President Biden for 2030.

Kimmel hopes U.S. installation vessels will be built in time for later offshore wind projects but vessel investments continue to lag behind project plans.

Meanwhile, faster permitting rules must be fast tracked, Sanjay Patnaik, a fellow at the Brookings Institution think tank, told Reuters Events.

“Without significant reforms to speed up permitting at the local, state and federal level, it will be impossible to build new, renewable energy infrastructure in the time needed to achieve the U.S. climate goals,” Patnaik said.

Suppliers wanted

Vineyard Wind 1 is located 15 miles south of Nantucket and Martha's Vineyard and several other projects are being developed in adjacent lease areas, including the Vineyard Northeast Wind project planned by Avangrid and CIP.

Vineyard Wind 1 follows the 30 MW Block Island offshore wind farm installed by Orsted off the coast of Rhode Island in 2016 and will soon be followed by the nearby 132 MW South Fork Wind project, owned by Orsted and U.S. utility Eversource and due to be completed this year.

The U.S. is yet to build a specialized wind turbine installation vessel (WTIV) and to comply with federal laws, Vineyard Wind had to use barges to transport equipment from New Bedford, Massachusetts to foreign flagged installation vessels anchored offshore. The Jones Act requires developers to use American-made vessels to transport goods into and out of U.S. ports.

The use of barges to transport components rather than loading up installation vessels on the quayside complicates logistics and pushes up project costs. Installers also have to tackle harsh weather conditions in the open seas.

“For our other projects we are keen on finding some better solutions than the barges frankly,” Kimmell said.

Urgent investments are needed in U.S. installation vessels. Utility Dominion Energy has commissioned the first Jones Act-compliant installation vessel but up to six vessels may be required to install 30 GW of offshore wind by 2030 and it takes around three to five years to build a new vessel.

A lack of investment in U.S. factories means that Vineyard Wind 1 and other early offshore wind projects have had to source most components from Europe, exposing them to global market pressures.

(Source: U.S. National Renewable Energy Laboratory's Offshore wind Supply Chain Road Map)

(Source: U.S. National Renewable Energy Laboratory's Offshore wind Supply Chain Road Map)

The supply situation is gradually improving, Moeller said, noting Prysmian's first U.S. cable production factory planned in Massachusetts and other facilities such as EEW’s first monopile factory in New Jersey, but far more investments are required. Suppliers are seeking greater transparency over future project timelines before they commit large investments to factories.

Approval challenge

Offshore wind projects can face opposition from local residents, fishing associations and environmental groups, requiring changes to project plans.

Vineyard Wind originally planned to route the undersea cable to land in Yarmouth, Massachusetts, but after facing opposition it moved the landing site to the neighboring town of Barnstable. Cables were buried beneath the seafloor and the beach and the developer is providing property tax payments and wider infrastructure improvements to the local community.

The project also took three years to gain environmental approval as it tackled first-of-a-kind issues for large-scale offshore wind development. In 2018, the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) expanded the scope of the review to take into account previously unavailable fishing data, a new transit lane alternative, larger turbine considerations and cumulative risks from multiple offshore wind projects.

The learnings from permitting Vineyard Wind should aid other offshore wind projects and BOEM plans to shorten the timelines, for environmental reviews. The bureau has set out proposals to streamline federal survey processes and increase design flexibility but is yet to issue a final ruling and rapid implementation is needed to aid projects looking to come online before 2030. Massachusetts is also working to establish a joint approach with federal agencies.

Without significant reforms, projects will continue to be held back by the high number of permits required at federal, regional, state and local levels, Kimmel warned.

"The long gap between when you get a bid awarded and you can actually start construction could be five years, and in those five years anything can happen economically," he said.

(Reuters - Editing by Robin Sayles)