Sustainable Shipping Gets New Berth

Centuries-old maritime craftwork and advanced technology help carbon-free seaborne trade.

It was a chance meeting that changed two lives. It may also change the way the world thinks about maritime shipping.

An accomplished sailor, Danielle Doggett loves tall ships—the large wind-powered sailing vessels that carry passengers and cargo. Her fascination with the big ships started in her teens, sailing on the Canadian side of the Great Lakes and eventually on the St. Lawrence II, a 72-foot two-mast brigantine built in the 1950s for youth sail training. “I have been taken by great sailing ships ever since,” Doggett explains. “The idea of shipping cargo, emissions free, as a viable business really inspired me.”

Doggett’s inspiration became a reality in 2010. While working aboard a wind-powered cargo ship in the Caribbean, she met Lynx Guimond, a world-renowned maritime wood carver who shared her passion for sailing and eco-friendly shipping. Within a few years they formed Sailcargo to build wind-powered cargo ships and established a shipyard in Costa Rica. Fast forward to today when they are building Ceiba, a wind-powered cargo ship. Ceiba is the largest vessel built in Costa Rica and the largest wooden vessel currently under construction in the world.

To build Ceiba, Sailcargo is using traditional arts and skills, locally sourced materials and meeting zero-emission goals. The endeavor is a unique blend of centuries-old building techniques combined with modern business savvy and cutting-edge technologies–including high-precision surveying.

Ceiba, a wind-powered cargo ship, is the largest wooden vessel currently under construction globally (Image: Sailcargo)

Ceiba, a wind-powered cargo ship, is the largest wooden vessel currently under construction globally (Image: Sailcargo)

The Shipyard

With Doggett as director and Guimond as technical director, Sailcargo wrote a business plan, developed a budget and pursued potential backers. “We thought we could do things better, especially financially, than what we saw while sailing in the Caribbean,” Doggett said. “We believed we could turn these ideas into a viable business.” She was right. In just over a year, they had a solid foundation with what would grow to be more than 150 investors from more than 20 nations.

Costa Rica seemed like the optimal location for their business on many levels. “I had worked at shipyards in Canada and Northern Europe that were cold and industrial,” said Doggett. “Costa Rica’s climate enables you to work year-round in a productive environment. Not only are we closer to the wood used for building, but the area is a global hub for green businesses.” Sailcargo selected a location near Punta Morales and constructed Astillero Verde (The Green Shipyard), an eco-conscious and carbon-negative shipbuilding facility.

Sailcargo has formed deep roots in Costa Rica. The company developed local supply chains, partnered on sustainable gardens, and built an educational pavilion where it offers classes on the environment and boatbuilding to local and international youth. Due to its location, climate and Sailcargo’s reputation and business approaches, Astillo Verde has become a magnet for skilled artisans and technical professionals.

(Photo: Sailcargo)

(Photo: Sailcargo)

The pavilion looks like something out of Peter Pan and the Lost Boys. It’s a rustic camp with residences, a dining facility, a large tree house, and a blacksmith shop for sharpening tools. The ship’s keel is aligned towards a channel leading to the sea. Inside the pavilion is a lofting floor that runs the length of the ship.

Doggett says a lot of thought and planning went into designing the shipyard and the alignment of the launch route, but they hadn’t had a comprehensive map of the facilities, launch route or as-builts of the ship. Then came the surveyor.

The Surveyor

A sailing enthusiast, adventurer and experienced surveyor, Damian Macrae discovered Sailcargo while browsing the Web. Macrae started his career in information technology, and studied surveying at the University of Tasmania. “Surveying was a great career option to get out of the office, but still with a strong focus on technology,” says Macrae, who resides in New Zealand. After graduation, he worked in mine surveying, where he got his first exposure to 3D laser scanning.

Today Macrae is a survey consultant with Allterra New Zealand, a survey distributor and solutions provider in Australia, New Zealand and the South Pacific. He had long wanted to visit Costa Rica and the call for experienced volunteers piqued his curiosity: Could the project use his skills?

Doggett was excited to have Macrae visit and identified several areas where surveying and scanning could provide valuable data. Surveying the shipyard would put his skills and equipment—a Trimble SX10 scanning total station and R10 GNSS receiver—to the test.

(Image: Sailcargo)

(Image: Sailcargo)

The Launch

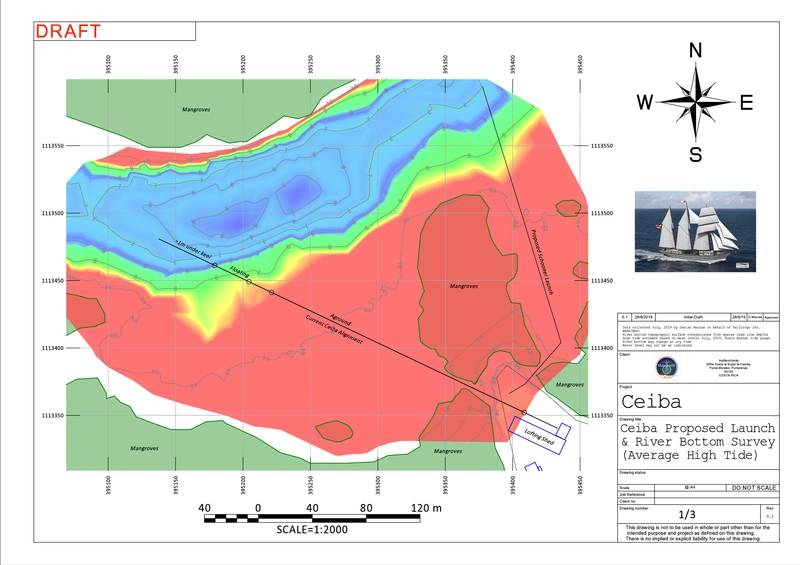

AstilleroVerde lies near the mouth of an estuary on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica, 15 miles off the Pan American Highway near the town of Punta Morales. The tidal flats between the shore and estuary channel experience high tides on the order of four meters (13 feet), and the alignment of the ship during construction was designed to minimize the launch route’s traverse over shore and shallow waters. “We want this launch to go smoothly,” said Doggett. “This ship will be a flagship for the country and a source of national pride. The president [of Costa Rica] is expected to be at the launch.”

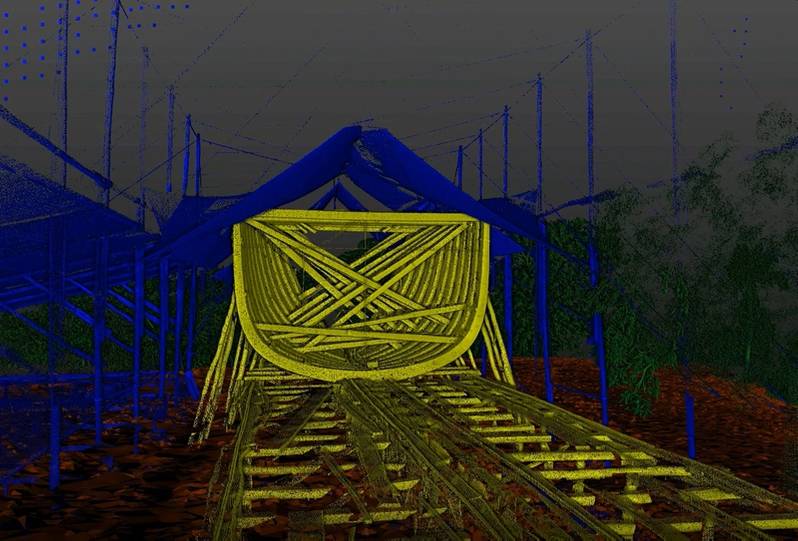

Macrae identified several challenges in developing an accurate 3D model of the launch route. “The water is shallow for several hundred yards, even at high tide, and there are a lot of unknowns about the bottom of the channel, such as how much is sand, mud or silt,” he said. The solution was a mix of old school and high tech.

Macrae and a Sailcargo team rowed into the estuary and put lead lines over the side for soundings. “We had the R10 in the boat and took sag measurements to come up with an offset. The horizontal positions were very tight, and we logged the soundings.” The team captured soundings in areas close to shore to allow cross-validation with laser scan data of the exposed mudflats.

Macrae wanted to include local control for the soundings and site survey, but there were many unknowns, such as origins of existing marks found on site, and lack of published values or reference framework (datums). “It was easy to determine the average high tide, so we decided to establish values for the control and reference everything to that, including our soundings and tide values.”

Macrae chose three existing survey marks around the shipyard and performed static observations with his R10. He processed the data in Trimble Business Center (TBC) against a continuously operating reference station (CORS) 5km away and produced average horizontal uncertainty of 10 mm (95% confidence) for all three marks. Macrae confirmed the results via a three-point resection using the one-second SX10, generating residuals of 8 mm. The resulting coordinate framework was used for all the sounding, topographic and scan work going forward. “Since I had two R10 receivers, I could be very efficient,” Macrae said. “While the static observations were underway I started an RTK job in the same datalogger project with the second receiver and walked the shipyard picking up points of interest.”

Macrae also used the SX10 to scan areas of the riverbed exposed at low tide. Using it as a total station, he back-sighted his local control and then scanned. “At low tide, I took the SX10 out about fifty yards from shore with my local control still visible. I did a full dome scan at each setup, collecting millions of observations of the river bottom. Because I was using existing control, the point clouds were automatically georeferenced to the rest of my data.”

The dense point cloud was combined with the manual soundings, RTK and optical observations to create an accurate 3D model of the launch route. “We realized errors could creep into the model from the soundings, so scanning provided a good check,” he said. Macrae then created several color-coded plan views with best and worst-case scenarios. Because the density of the ship has not yet been determined, he used a range of values for Ceiba’s final displacement.

Doggett said the results of the soundings and scanning were welcome as they confirmed that the alignment was good, and the launch route accurate. Both the launch route across the ground and the shallow flats will be lined with logs to the point where the ship can float on its own. “There might be minor variations in the tide beds before the ship is complete, but the 3D model gives us confidence that the launch will go smoothly,” Doggett said.

(Image: Sailcargo)

(Image: Sailcargo)

The Map

Sailcargo’s jungle shipyard had grown organically, with structures built as needs arose. Prior to Macrae’s visit there was no formal map of the property, terrain or structures. Macrae provided one using SX10 scan data gathered in just a day and a half of fieldwork. Areas not suitable for scanning, such as break lines and features in tall grass, were observed traditionally with a range pole and an R10 or SX10.

Macrae traversed around the shipyard with the SX10, taking a full dome scan at each setup. Each scan, including image capture (used for automatic point colorization and panorama creation in TBC), took just under fifteen minute and captured an average of 120 megabytes of data, with 8-10 million points each. Macrae collected nearly 40 scans in total before combining the scan data, RTK, traditional total station observations and soundings into a single TBC project. From this dataset, TBC automatically extracted ground, building, power-pole and tree points. With the bulk of processing on the massive data set completed automatically, Macrae needed roughly two hours to clean up the point cloud and create regions of interest such as Ceiba’s frames, specialty buildings and fences.

With the processing complete, it was a simple task to plot contour lines, building footprints, fences, road edges and utilities. Macrae produced a topographic plan that can be used for planning, drainage design and logistics. He also used Trimble Clarity to create a 3D fly-through of the site and true color point cloud views, enabling the team to view it online and share it with investors and partners. “We had never been able to view our camp in this manner before,” said Doggett. “We were not sure where our facilities were relative to the boundaries.”

(Photo: Sailcargo)

(Photo: Sailcargo)

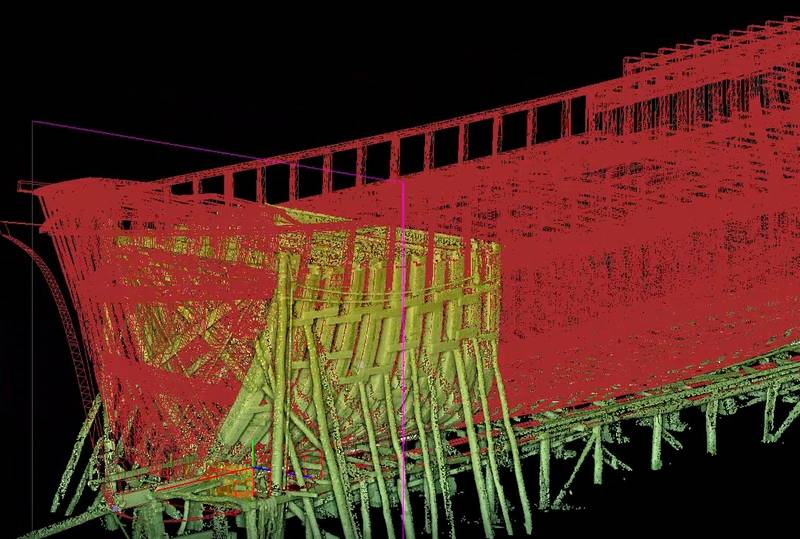

The Ship

At the time Macrae visited, Ceiba’s keel was down and 13 of the ship frames were in place. Although Sailcargo makes hand measurements as the ship is constructed, a scan would allow them to check design fidelity. With several setups of the SX10, Macrae produced dense point clouds registered to reference marks on the ship. “For most setups around the shipyard, I used full 360-degree scans with the SX10, but for finer details of Ceiba’s frame, I chose a smaller area with the polygon selection tool on the TSC7 [data controller],” he said. This yielded denser point clouds where more detail was needed while keeping the average setup time under ten minutes.

“We had enough data to align the digital CAD model of the ship against the georeferenced point cloud,” Macrae said. Once the point cloud and CAD model were aligned, cross sections of each frame were plotted for as-built checking.” The team could see the cloud in Trimble RealWorks Viewer and online via Clarity. 3D animation allowed them to compare the cloud with the original design. Doggett says she doesn’t know of any other wooden ships of this size scanned this way while under construction. “I had seen other scans after a ship had been completed, but there was a lot of detail missed. This gave us a unique way to see how well we were sticking to the design.”

(Image: Sailcargo)

(Image: Sailcargo)

The End

When we interviewed Doggett in April 2020, 75% of the frames were in place and planking would begin by fall. “We have been given a way of looking at and measuring things that we’ve never had before,” Doggett says, “and are very grateful to Damian for helping make this happen.”

For Macrae, it was more than a wonderful holiday to a place he’d always wanted to visit. It was an opportunity to test the equipment his customers are fast adopting. “Scanning Ceiba, the shipyard, the tidelands and generating the topo plan from point cloud data was a good exercise on how much we can do with the SX10,” said Macrae. “We have TBC, and it was easy to extract features from the point cloud. It is a good example of mixing traditional topo points with data from a point cloud.”

As the principal structure of the ship nears completion and other construction begins, Doggett says she is reaching out to new investors. As framing is finalized, she adds, another scan would be greatly welcomed, too. Doggett asks, “Anyone interested in pitching in on a once-in-a-lifetime surveying adventure?”

(Photo: Sailcargo)

(Photo: Sailcargo)

Introducing Ceiba

The largest wooden vessel under construction in the world now has a name: Ceiba, inspired by a group of tree species native to tropical regions of the Americas and West Africa. Ceiba is the flagship vessel of Sailcargo, an eco-friendly company building zero-emission ships.

Ceiba was designed by naval architect Pepijn van Schaik of Manta Marine Design B.V., who also designed Tres Hombres, a smaller cargo ship that Doggett once crewed. When complete, Ceiba will be a three-mast schooner, 45 meters long, with an eight-meter beam, a rigging height of 34 meters. Cargo capacity will be 250 metric tons / 350 cubic meters, plus additional on-deck space. It will be nearly 10 times the size of Tres Hombres.

Wood for Ceiba was sourced locally and included trees felled by tropical storms. Frames are Spanish Cedar, which is in the mahogany family and not a true cedar, while the stem and framing are Guapinol, also known as Jatoba. Sailcargo has implemented a planting program to offset timber used.

Ceiba will also feature two high-efficiency 120 horsepower electric motors. The variable-pitch propellers will generate power when the ship is under sail by working as underwater turbines to charge batteries and meet onboard electrical needs. Since routes will include equatorial regions, solar will also be added.

Sailcargo is not saying that wind power would be a practical replacement for all fossil-fuel-based-seaborne commerce. But it can provide another option and there is a growing demand for such alternatives. Companies with environmentally friendly and carbon neutral products can now complete the supply chain by offering zero-emission marine delivery. Sailcargo believes successful businesses must follow the basic tenet of providing what customers want.