SOVs – Analyzing Current, Future Demand Drivers

At a high-level, there are three solutions to transferring technicians from shore bases to offshore wind farms for construction and O&M activities: crew transfer vessel (CTV), helicopter, and SOVs/CSOVs.

SOVs and CSOVs generally house 60-120 technicians offshore for a few weeks at a time, allowing them to transfer to structures on integrated heave compensated gangways, by daughter craft or on CTVs. The vessels are also equipped with cranes, storage, and small workshop areas.

SOV: Service operations vessels, generally on long-term charter to a wind turbine OEM or offshore wind farm operator to service and maintain equipment during the operations period of the wind farm. A typical SOV will accommodate ~60 technicians. A typical SOV is diesel electric and increasingly includes dual fuel flexibility and battery energy storage systems.

CSOV: Commissioning service operations vessel, generally on short-to-mid-term charters for project construction, turbine installation and commissioning, and initial service warranty periods. A typical CSOV will accommodate ~120 technicians. A typical CSOV is a battery hybrid diesel electric, ready for dual fuel operations.

Lower day rate CTVs are often used for daily transfer of 12-24 and increasingly 30+ technicians on a daily basis and have an advantage when windfarms are close to shore. There is a trend for CTVs to be built with crew accommodation, allowing the vessels to stay offshore overnight, and to serve accommodation and construction vessels (including CSOVs) for extended periods.

In some applications, helicopters are cost competitive, although their use is relatively limited.

- Tier 1: purpose-built vessels for offshore wind with in-built crane and gangway.

- Tier 2: Generally, oil & gas tonnage (MPSVs, PSVs, etc.) with fixed gangway, serving oil & gas and offshore wind markets.

- Tier 3: Generally, oil & gas tonnage (MPSVs, PSVs, etc.) with temporary gangway, serving oil & gas and offshore wind markets.

Market Drivers

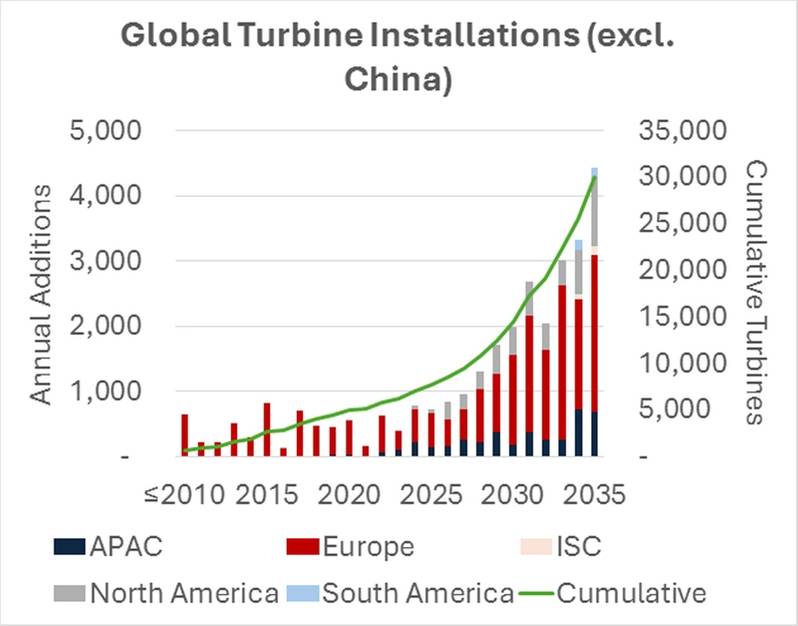

When we look to understanding SOV/CSOV demand, we look at the number of turbines installed and planned. Given that three international OEMs (Siemens, Vestas and GE) currently dominate the global offshore wind space outside of China, we do not look at demand for SOVs/CSOVs as having a linear relationship to the number of wind farms or turbines installed. We look to see where a large number of wind turbines are concentrated in relatively close proximity, generally in a very large wind farm or in a project cluster featuring two or more wind farms, which will give the economies of scale required to justify a SOV/CSOV. We should note that some Chinese OEMs are targeting international market expansion, which may result in the demand base becoming more fragmented.

Although the developer space is more fragmented, we look to the developers of large wind farms and/or developers of geographically close project clusters. Developers in this space include Ørsted, RWE, Equinor, SSE, etc.

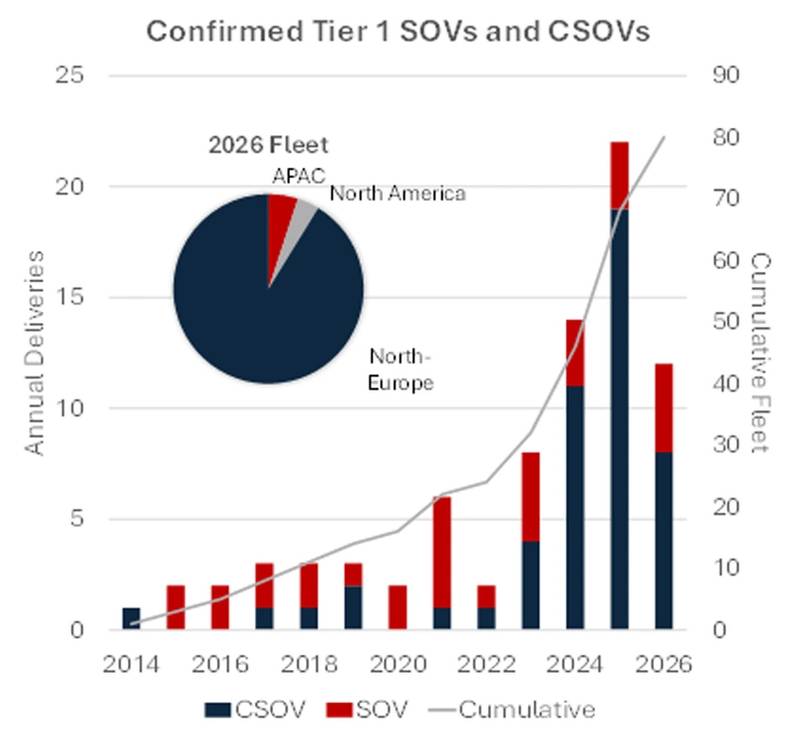

Outside of China, the global installed and operational turbine base amounted to ~6,200 turbines at the end of 2023. The Tier 1 SOV/CSOV fleet stood at 32 vessels, 31 one of which being active in Europe. ~480 active CTVs served operating and under construction wind farms in Europe, APAC, and the USA.

~8,300 turbines are forecast to be installed globally (excluding China) between 2024 and 2030 and close to 15,500 in 2031-2035, as global offshore wind capacity (excluding China) grows to ~380 GW of capacity at the end of the forecast period. The high-level conclusion that one can make is that more turbines will drive the demand for more Tier 1 SOVs and CSOVs. Source: Intelatus Global Partners

Source: Intelatus Global Partners

Until now demand Tier 1 vessels in the maturing European offshore wind segment has been by scale, more wind turbines, wind farms being built further offshore, clustering of developer projects (i.e., many multiple projects in close geographic proximity), and consolidation of wind turbine OEMs. 73 Tier 1 SOVs and CSOVs are active or under construction in the North European wind segment. Tier 2 and Tier 3 walk-to-work (W2W) vessels are currently active in the segment, but as oil & gas activity returns, we anticipate that supply of the vessels to offshore wind projects will reduce, driving demand for additional CSOVs.

Outside of China, the Asia Pacific region is in the early stages of wind farm development, with one active Tier 1 SOV and three Tier 1 CSOVs in construction for the comparatively near shore Taiwanese market, which is also actively served by CTVs. Oil & gas offshore support vessels have been widely deployed to support construction logistics. South Korea, Japan and, in the longer-term, Vietnam and Australia, are forecast to be the largest APAC offshore wind markets and therefore sources for vessel demand.

The U.S market is preparing for a period of large wind farm construction and operations, with three Tier 1 SOVs, two on long-term charter for operators and one for an OEM. Construction and commissioning have been supported by several Gulf of Mexico Tier 2 and 3 vessels, the supply of which is expected to find core deployment in an increasingly active Gulf of Mexico oil & gas segment in the short-to-midterm. The 2024-2035 period is expected to witness strong growth in the U.S., as offshore wind spreads from the North and Mid-Atlantic, to the Pacific Coast and the Gulf of Mexico, effectively creating three-four sub segments for SOV/CSOV demand. Source: Intelatus Global Partners

Source: Intelatus Global Partners

The Question of Emissions

Given that SOVs and CSOVs operate in a segment targeting reduced emissions, and many operate in the North European segment, characterized by a general strengthening of emissions reduction measures, more than 20 active or under construction vessels feature fuel flexibility through dual fuel engines and (space for) a bunkering system. Currently methanol is a preferred energy carrier although hydrogen and liquid organic hydrogen carriers also feature.

Battery energy storage systems feature extensively as do electric drives.

Designers and Builders

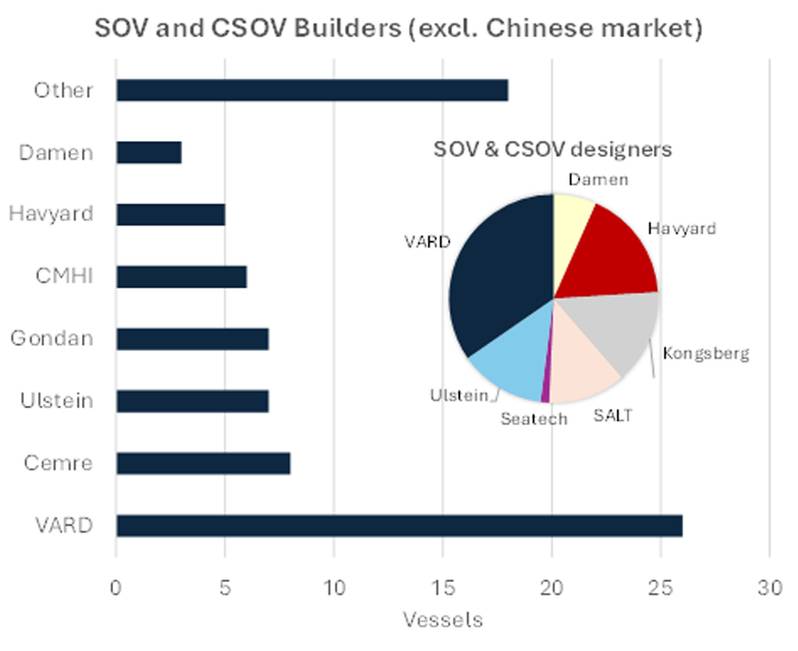

SOV and CSOV owners have generally sought pricing from Norwegian yards (who generally build the hulls in countries including Vietnam, Turkey, Romania, and Spain) and China.

According to CSOV owner Integrated Wind Solutions, the contracting price of a Norwegian newbuilding has risen from €60 million to €68 million between Q1-2021 and Q1-2024. With a hull built in Spain or Romania, the cost rose from €52 million (2021) to €66 million (2024). In the same period, a Chinese built CSOV for the European market would attract a yard price of €44 million (2021) and €61 million (2024). Based on this data, we note that the premium for a Norwegian built vessel fell from ~25% in early 2021 to ~12% today.

The biggest new building premium is found in the USA, for a variety of reasons, where the three tier one SOVs are being built for ~€87-168 million.

VARD is a leader in the design and construction of SOVs and CSOVs, building hulls in Romania, Spain and Vietnam that are completed and commissioned in Norway. The company is also building a vessel through its Fincantieri Bay Shipbuilding subsidiary in the USA. The most popular design in the VARD 4 19 platfrom.

Far behind VARD is the Turkish yard Cemre, building Havyard and SALT Ship designs, Norway’s Ulstein, Spain’s Gondan (SALT Ship Design and Kongsberg designs), and China’s CMHI building Kongsberg designs.

Ten yards account for the remaining vessels. Source: Intelatus Global Partners

Source: Intelatus Global Partners

The Future Looks (generally) Bright

The market fundamentals, reflected by an increasing number of turbines being installed and operational coupled with a likely reduction of Tier 2/3 vessels, support a growth in the vessel supply-side.

Whereas, SOVs are generally built against long-term charter and therefore have a certain amount of financial security, CSOVs are more exposed to redeployment risk and there remains a concern that overbuilding of a commoditized vessel may result in future oversupply as seen in the oil & gas OSV space in the 2008-2014 period.