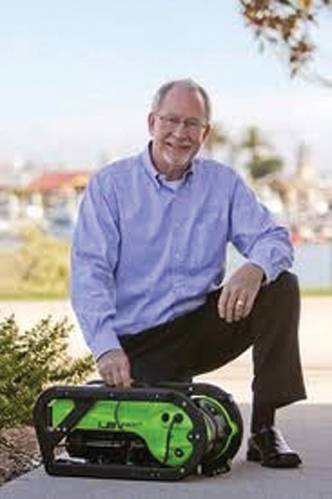

Don Rodocker: The Man in the Sea

In the early days of subsea technology, there were a number of pioneers: men and women who stepped over the edge of what we knew about the underwater world. These individuals left the comfort of solid ground to explore beneath the waves and report back to the rest of us what they had seen. They pushed boundaries, raised the stakes and in some instances opened our minds to the possibilities. They were subsea visionaries. Today, those boundaries continue to be pushed, and undersea technology, now more than ever, is reaching new heights. The pioneering spirit has never been better represented than in the father and son team of Donald and Jesse Rodocker, founders of SeaBotix Inc. LLC. Don began his career as one of the early pioneers in the diving industry. His cutting edge designs in dive equipment, hyperbaric support systems and remotely operated vehicles laid the groundwork for many of the systems we see operating in the field today. His son, Jesse, has also had an impressive career working on high profile projects such as the search for Amelia Earhart, counter mining measures for WWI and WWII seamines in the Baltic Sea and the archaeological investigation of a WWII Japanese midget sub. MTR recently sat down with Don Rodocker to not only get a glimpse into the origins and history that led up to the creation of SeaBotix, Inc., but to also visit, if just for a moment, that golden age of subsea technology.

You’ve had an illustrious career in the subsea industry. Can you recap some highlights?

I started diving in 1965. I was in the Navy stationed at the Bremerton Naval base off the coast of Washington State. I would go snorkeling in the waters there – which were about 45°, a bit on the chilly side. You could snorkel for about 30 minutes or so, and then you would have to jump out. It would take about that long just to warm up and to get the color back in your lips. Then I would jump in again, maybe for 20 minutes and jump back out. It would take progressively longer to warm up. Mind you, I was not wearing a wetsuit of any kind. Still, I was hooked. The incredible flora and fauna was very intriguing. There were so many alien creatures. And there was treasure down there. You would find something on every dive, anchors and shell casings, all kinds of things. It was so interesting to me. Since I was limited by my lack of thermal protection, I finally decided to make myself a wetsuit. I got a pattern, bought some material and made a shorty. I thought I had died and gone to heaven. I could stay much longer and see so much more that way. Then the limitation was not thermal but rather how long you could hold your breath. So I decided to take a SCUBA course at the YMCA and got certified. I then got a part-time job so I could afford some equipment and bought a custom wet suit. That’s when life really got good.

Sounds like you made it happen. Serving in the Navy and a part-time job kept you busy.

Yes, I was serving in the Navy and married with kids. I had a full plate. I remember there was a dive locker on the ship I was on, which was a submarine tender that we used as a base for all these reserve ships. So we would go into these decommissioned ships, haul away all the machinery and paint the bilges. Just go through them completely. So during this time I got a part-time job, and that allowed me to buy more diving equipment. On board the ship I also started making my own diving equipment including weights. You couldn’t tell them apart from the ones you bought. I then bought a double manifold from someone and got a couple of tanks and had hydros done on them. I made my own harness.

So you started building diving and subsea equipment from the beginning.

Yes, I didn’t really have a choice. So then I left Bremerton, went to Naval school and got qualified in a very short period of time – less than three months. As a reward, they gave me Navy SCUBA School. I became the ships diver on the submarine. This happened just in time for a six-month Western Pacific cruise, so I got to do some really exciting diving which continued all over the world. At the end of that tour, I was getting out of the Navy, and they tried to entice me to stay. They asked me what it would take. I said I wanted second-class diving school, first class diving school, saturation training and assignment to the Man in the Sea Program. Well, they laughed and said they could get me one school and one duty station or maybe two schools, but all four is asking too much.

What is the Man in the Sea Program?

It was a Naval initiative started in 1964 when the first Sealab was established. There were three Sealabs, which were experimental underwater habitats. They were part of the Deep Submergence Systems Project.

So no cigar.

No, and I said, “Well, you asked.” But then when I got back from the Philippines early – about a month later – the boat came in. I met it, and they said, “Hello, Mr. Man in the Sea.” So then I had to make a decision: I had to either sign on or get out and head to college as I had planned.

Did they let you participate in all four schools?

Yes, I did all that. I got an amazing education in the Navy. From nuclear power school to jet propulsion school to air conditioning and refrigeration school, machinery repair school and then all the diving schools.

What was it like being involved in the Man in the Sea program?

Our job was to carry out the operational and technical evaluations on the Sealab III. Sealab III was really Sealab II after an overhaul. Both were located off the coast of La Jolla, California. Sealab III was also, about three times deeper than Sealab II. We were also support for the landing class ship IX501, also known as the Elk River or what was more affectionately referred to as Moose Creek. We put the thing together, sorted out a bunch of things wrong with it and then did some saturation dives and trials. We hit 1,010 feet. That was the world record at that time.

Another first.

Yes. So following the Navy I started Saturation Systems Inc. with Chris DeLucchi. One of the things we did early on was a dive on the Andria Doria. This was the first commercial saturation dive of a salvage operation ever.

That must have been quite the feat in those early days.

It was. When we did the dive on the Andria Doria we built a closed circuit diver gas recovery system because we could not afford the gas. We were in Fairhaven, Mass. rolling cylinders down the dock. That was first generation. Then we did another generation for Seaway Diving at Sat Systems. We were interested in recovering the purser’s safe on the Doria, and the objective was to cut a hole in the wreck. To do this we built a portable saturation habitat called “Mother” that was lowered to the side of the wreck where we could breathe a mixture of 92% helium and 8% oxygen. This would allow us to work for several days before decompressing and surfacing. We did not get what we were after, but we did get a great deal of publicity. That publicity really took us to the next stage, which was to build equipment and use the money we made there to do more treasure diving. The two would then feed on each other.

You went back to the Doria years later with a SeaBotix ROV as well.

Yes. We went back on the 50th anniversary of the sinking just to bring new technology back to the Andria Doria. We used a SeaBotix LBV200 on that dive, and did a bunch of investigation on the wreck.

What followed the earlier dives on the Doria?

We then got a sizable contract with a Norwegian company called Seaway Diving who was just setting up their saturation diving program. This was to support the oil operations in the North Sea. We got heavily involved and ended up working with a company called Draeger.

We were working with Seaway Diving when Draeger had started building saturation diving systems and of course rebreathers, including semi-closed and closed circuit systems rebreathers. We did some testing with those and some evaluations on the diving systems they were building.

That company grew, and we sold lots of diving systems. It grew fast over a five-year period. We had 130 employees, but we were underfunded. Most of the units we were shipping from San Diego were going to the North Sea and the Gulf of Mexico. There was a lot of freight involved, which made it very expensive. So once the technology caught up and other companies could build similar equipment, it made it very competitive. Also, the way we wanted things done and how we thought they should be done was not really what the industry was about. It was do the minimum to get the job done. We were quite a ways away from that ideology, so we decided to shut it down. We shut it down and disbanded.

You were really at the forefront of underwater technology on several levels.

I then started a company called Gas Services Offshore Limited. It was to develop a system for gas recovery. I developed a system called the Gas Miser, which was a deep diving gas reclaim system. Chris DeLucchi and I also developed the Sat Hat, which was a versatile dive helmet. It had a demand regulator and a push-pull regulator with mixed-gas reclaim capability. It could also be used with open circuit, free flow mode or with a semi closed-circuit rebreather.

What were some projects in the field that used the systems?

We participated in raising five tons of Russian gold. That got things started with that company. That company went on to become the Pressure Products Group, and later DiveEx was one of the companies that we acquired. It still exists today. I then sold the company and was approached by an offshore-diving supervisor. He had built this concept of an ROV and I ended up funding that. I got heavily involved. The company was called Hydrovision. Hydrovision produced the Hyball.

Were those the origins of your involvement with ROV technology?

Yes. We spent a bunch of money and developed this vehicle. There is a little over 400 Hyballs out in the field. It was the first production built ROV. The Hyball 225 was known in the field as the eyeball. It was an incredible learning experience. At that time I sold the balance of the companies known as Pressure Products Group. I then became semi-retired in Seattle but continued to dabble in hyperbaricoxygen and ROVs. I wanted to develop a small ROV. It was really what we wanted to do from the first concept with the Hyball. But now the cameras had shrunk quite a bit; it was much easier to shrink this thing down. We worked with a company in Vancouver that built a small ROV called the Scallop. They were interested in selling the IP on this and another system. I looked at it and got one, but you couldn’t really get it across the pool. I used this as a proof of concept for a small vehicle and went off of my boat with a drawing board. We built a prototype of the LBV in my shop in Washington. We did some initial testing and built some thrusters that had certain criteria that we had to meet, such as a 3-knot current minimum. We determined how much thrust we needed to have. We built thrusters that would produce enough to propel it at 3-knots. It was in the early days of solid modeling and the cost to do the solid modeling was quite expensive.

Did this early investigation into smaller ROV technology lead to the inception of SeaBotix?

My son, Jesse Rodocker, was down in Austin when he called me and said, “It’s time to get the Little Benthic Vehicle off the shelf. The market is ready.” I said, “If you will help me, let’s go for it.” So we did. In 1999 we put together the business plan and started developing the framework for what is now SeaBotix Inc.

What are some of the concepts behind the SeaBotix LBV and vLBV ROV lines?

We progressed the concept and design and really did a lot of testing and trials to make sure it was capable. The problem with the Scallop was it wasn’t able to get across the pool because the thrusters were too far apart. You have to remember, when you’re talking about the smaller robots there is also an optimum at the size endpoint. The smaller systems or the micro ROVs just cannot carry the payload and deliver the payload with maneuverability. You can pile a whole bunch of stuff on it, and it struggles to get there. You can pull an 18-wheeler with a Volkswagen, but you don’t go very far or very fast. Today, our systems are being used all over the world in all sorts of applications. We can carry the payload our end users need and maintain maneuverability. In one application, for example, some of the early adopters were able to take the vehicles and do inspection work. The first tunnel inspection was more than 1,100 meters inside a pipeline. We have since gone past two kilometers. There have been many “firsts” achieved with our vehicles. We dealt with all of those early challenges, and we also dealt with the price point. By pushing the price down and taking the risk, we were able to increase the volume substantially. We are now just about to go over 1,000 units sold.

So looking toward the future for SeaBotix …

We will continue to do what we do best: push the envelope and continue to deliver industry-leading technology.

(As published in the March 2013 edition of Marine Technologies - www.seadiscovery.com)