The Challenge of Responding to Arctic Oil Spills

The U.S. Arctic is no longer the place it once was.

The environment north of the Yukon River and beyond the vast Brooks Range is warming rapidly. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) scientists predict that by 2020-2030, the Arctic could be nearly free of sea ice during the summer. Open seas will expand opportunities for maritime transportation, tourism, and oil and gas exploration in the region. But as a warming Arctic opens up vast opportunities for commerce and development, it brings with it unprecedented challenges, especially for protecting Alaska’s extensive coastline and incredible marine life.

Increased vessel traffic to newly accessible oil reserves and navigational routes raises the likelihood of accidents at sea and along the Alaskan coast. Both industry and government will have to deal with and manage the resulting medical emergencies, search and rescue cases, and environmental pollution.

Addressing Oil Spill Response

One area that has received a lot of attention in the wake of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon rig explosion and well blowout is oil spill response. All oil exploration and production operations in U.S. waters are required to have response equipment accessible in case of a spill. The temperate waters and dense industrial coastline of the northern Gulf of Mexico are well equipped to support oil spill response when compared to the remote Alaskan Arctic. Vessels crossing the Arctic Ocean may find themselves with comparatively little response equipment on board. They also would need to have agreements in place with oil spill removal organizations, which, at present, only have equipment and infrastructure in limited locations on Alaska’s North Slope.

Despite the best efforts at prevention, oil spills will happen in the Arctic. When this occurs, the expectations for response should not be the same as in the Gulf of Mexico or other areas with significant coastal response assets and infrastructure. Instead, everyone involved needs to be ready to work with the limitations of the Arctic’s extreme environment. The region has highly variable and harsh weather conditions including ice which could interact with spilled oil, and limited infrastructure for transportation, food, and housing for response personnel.

Questions remain about what kind of impacts an oil spill might have on Arctic marine ecosystems and how best to mitigate the effects. Potential impacts could affect not only protected species but also extend to the subsistence lifestyles which are deeply engrained in the culture of Alaska Native peoples and include activities such as hunting for bowhead whales, ice seals, and walruses. In addition, not as much background environmental data exists for the Arctic as for other U.S. coastal locations—and since the Arctic is in a state of change, what background data is known will not be viable indefinitely. When an oil spill does occur, a lack of baseline data for comparison may affect NOAA’s ability to assess and restore injuries to natural resources. We have been fortunate not to have a large release in the Arctic, but the lack of an actual spill also means that data to inform restoration decisions, such as ecosystem recovery rates, is limited.

For these reasons, NOAA’s Office of Response and Restoration (OR&R) is working proactively alongside other federal, state, and tribal agencies as well as industry, academia, and nonprofits to prepare for and understand the consequences of oil spills in the Arctic. OR&R serves as a center of expertise in preparing for, evaluating, and responding to oil spills and other threats to coastal environments. Tailoring its years of experience to the Arctic’s challenges, OR&R is developing the tools, fostering the relationships, and building the knowledge base to help deal with the unique demands of an Arctic oil spill.

Specific Efforts

To assist emergency response decision makers such as the U.S. Coast Guard and the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement, OR&R is developing the technology—specific to the Arctic—to manage environmental and response information. One such tool is NOAA’s Environmental Response Management Application (ERMA) for the Arctic Region. Now accessible to the public, Arctic ERMA is based on the same platform as NOAA’s Gulf of Mexico ERMA, which federal responders used successfully during the Deepwater Horizon/BP oil spill in 2010. ERMA is a web-based mapping and data management platform that brings together and creates a visual overview of information on environmental conditions and ongoing response and damage assessment operations. Arctic ERMA is available online at https://www.erma.unh.edu/arctic.

Effectively preparing for the threat of an Arctic oil spill requires leveraging the tremendous knowledge and experience of the many people with Arctic expertise, including local residents. Additionally, the U.S. government should continue work with industry, academia, nonprofits, and other Arctic nations to bring the best available technology to oil spill response, both to reduce the likelihood of a polluting event and to minimize harm should one occur. During such an incident, decisions need to be made based on current conditions, infrastructure capacity, and—of course—sound science. NOAA’s OR&R is focused on fostering the working relationships needed to make informed scientific decisions about oil spill response and environmental restoration.

The Best Response: a Good Defense

The best executed response is a prepared response. This means putting into practice mandatory response plans. OR&R has participated in a number of these exercises. In the summer of 2012, for example, NOAA, the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE), and the U.S. Coast Guard participated in an industry-sponsored theoretical training exercise simulating an oil spill in Alaska’s Chukchi Sea. Representatives from all levels of government and industry took part in the drill, which featured a demonstration of real-life challenges expected during a spill in this remote area. The drill tested the government and oil industry’s ability to make rapid decisions based on environmental, logistical, and operational data. Data ranged from the availability and deployment of response assets (e.g., boom and skimmers) to expected wildlife impacts. Overall, the drill was a success but clarified a sentiment already present among responders: The scope and complexity of an Arctic spill requires special considerations not present during spills elsewhere in the U.S.

Equally important for effective emergency management is fostering solid relationships with affected communities. In this vein, NOAA, along with several other state and federal agencies, has been attending a series of workshops designed to engage Alaskan Arctic communities on issues of oil spill response and restoration. NOAA’s goal is to start building relationships between those who know the local environments and those emergency responders and restoration experts who will need that guidance in the event of an oil spill. So far, these workshops are broadening OR&R’s understanding of how closely people are tied to natural resources in the Arctic—and how, together, the response community might be better able to plan, prepare, and respond to spills to minimize negative consequences.

Assessments, Training and Models

It is through these partnerships that NOAA’s Office of Response and Restoration is able to identify the scientific and operational unknowns in dealing with Arctic oil spills. Frequently, this translates to offering training and hosting discussions on critical response and restoration issues. OR&R oceanographers and scientific support staff share their knowledge of modeling the projected paths of spilled oil, the best mechanical methods for recovering oil, and whether alternative response countermeasures, such as in situ burning and chemical dispersants, should be used. At the same time, OR&R hopes to improve the current, incomplete understanding of the interaction of oil in, under, and above floating sea ice and of which protection strategies, such as booming, work best in each location.

As a natural resource trustee, OR&R also is working diligently with other federal, state, and tribal trustees to better prepare for a natural resource damage assessment in the Arctic. This is a complex scientific and legal process that often involves years of work and negotiations over what injuries occurred and how best to restore the environment based on the injury. The injury is compared to pre-spill conditions, making an understanding of the baseline essential—even as that baseline is changing in a warming Arctic.

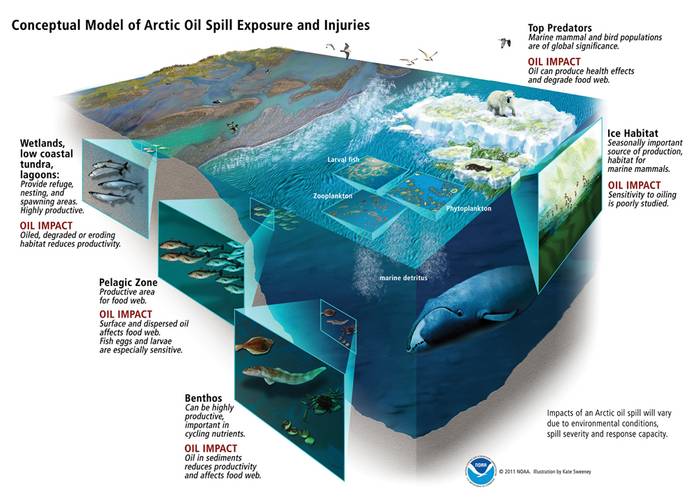

In advance of environmental injury, OR&R has created a conceptual model of what would happen to Arctic habitats and wildlife during a major spill. The model lays out all the possible ways oil could move through the marine environment and how fish, invertebrates, birds, and marine mammals could be exposed to oil at different levels of the ocean.

This is particularly important because shipping creates a high risk for oil spills on the surface of Arctic waters, which could then impact the sensitive species found there.

Fortunately, since 2009, OR&R’s scientific support coordinator for Alaska has served on an advisory committee to a special oil industry research group trying to resolve remaining research questions before major oil exploration and production occurs off the northern Alaskan coastline. In particular, this research program has focused on determining the viability of using chemical dispersants during future responses to Arctic Ocean oil spills.

Looking Ahead

The future of the Alaskan Arctic almost certainly will see increased development, and along with it, greater chances of oil spills. It is imperative that everyone—government, industry, nonprofit, academic, tribe, and resident—work together to understand the benefits and risks of these activities and make decisions founded on sound science. Where there are risks, NOAA’s Office of Response and Restoration will be working to bring the best available technology, partnerships, and science to ensure the Arctic’s future is a healthy one.

(As published in the December 2012 edition of Marine News - www.marinelink.com)