Region in Focus: Norway’s West Coast Shipping Tech Hub

Two load-bearing pillars of Norway’s leading maritime industry cluster in Sunmøre on the country’s west coast – offshore energy and the expedition cruise sector – took severe knocks from plunging energy prices in the 2010s followed by COVID-19. However, a recent tour of the region found the cluster in recovery mode.

At the time, the cluster’s diversification strategy was to dive into the emerging expedition cruise sector: small, highly sophisticated ships designed to operate in some of the world’s most sensitive environments incorporated features including the highest ice-class, latest waste heat recovery systems, and some of the cleanest-burning engines. The outlook was promising, until COVID-19 brought the global cruise industry to its knees.

But just as the cluster moved rapidly from primarily a fishing economy into offshore energy in the 1970s, its strategy of nimble diversification continues. Today, aquaculture is booming and new initiatives promise rapid development in the offshore wind sector.

“Oil and gas rates… are going up quite far,” said Daniel Garden, CEO of cluster manager GCE Blue Maritime, in assessing the current situation. “Now, all those laid-up PSVs have work again.”

He adds that although “there is a lag to get customers back to planning their holidays, it looks like [expedition cruise] vessels are back in operation, too. Not all are fully booked … but the newbuild program has started again”.

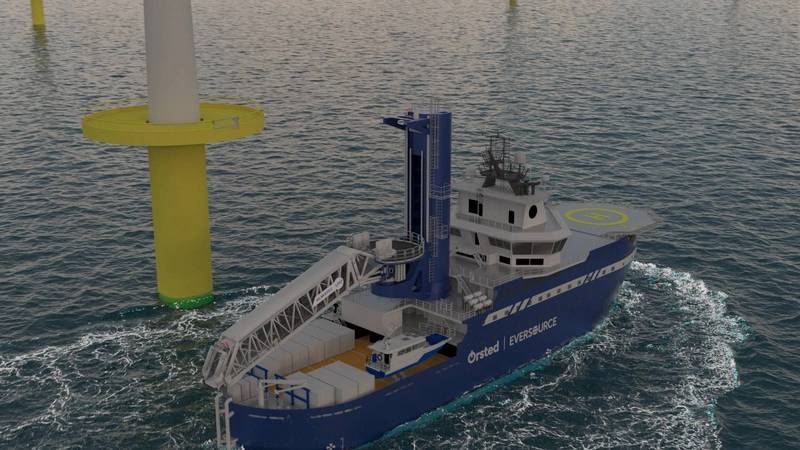

And even if Norway doesn’t have much use for new windfarm support vessels (SOVs) with almost no turbines in place itself, installers and developers across Europe have urgent requirements and Norway’s attractive export credit arrangements provide a valuable incentive. Here’s a whistle-stop tour of companies in the area.

Norwind Offshore took delivery of Norwind Breeze earlier this year. Credit: Norwind OffshoreNorwind Offshore

Norwind Offshore took delivery of Norwind Breeze earlier this year. Credit: Norwind OffshoreNorwind Offshore

Start-up Norwind Offshore is an interesting case study. Established during the pandemic, it is an alliance between offshore veterans Volstad, Farstad and Kleven. Later, Danish investment fund Navigare Capital Partners joined the party.

Norwind’s original plan had been to convert laid-up PSVs into SOVs, but spiralling energy prices put paid to that. “There are now zero PSVs in layup,” said Svein Leon Aure, Norwind CEO. “Secondhand prices for PSVs have increased 50%, so we cannot get hold of cheap ones to convert – it would cost close to a newbuild.”

So, Norwind is operating just one converted PSV – Norwind Breeze, built as Skandi Responder in 2015. Aure does not appear to be losing sleep, however; his company is demonstrating a willingness, in line with others in the West Coast cluster, to value local shipbuilding expertise.

The Norwind Breeze conversion sets an important course for the future. Underdeck mud and slop tanks are now open spaces which could house banks of batteries. With typical Norwegian ingenuity, Norwind wants to equip its vessels with technology similar to shore power, but for plugging into wind turbines. Aure says it may be possible to power all SOV operations this way, using 100% battery power, in future, making offshore operations completely carbon-free. Norwind is planning a series of new SOVs. With this strategy, the company has commissioned nearby shipyard group, Vard.

Battery friendly: the DC set-up aboard an ESS-equipped VARD vessel. Image courtesy Vard

Battery friendly: the DC set-up aboard an ESS-equipped VARD vessel. Image courtesy Vard

Vard

The shipbuilder’s design ingenuity is clear to see in its latest SOV for Norwind. New service vessels are being developed to use offshore wind power, with hulls designed to optimise hull dynamics on the outside while maximizing internal space for banks of batteries, explained Vard’s Research & Innovation Manager Henrik Burvang.

In fact, some 87% of Vard’s current orderbook – with construction split between Romania and Norway – will either be equipped with, or ‘ready’ for, huge banks of batteries. Close to half of engines will be built to use alternative fuels like ammonia or methanol. These developments are part of Vard’s “Zeroclass,” vessels which are designed to operate within a zero-carbon paradigm. Currently, Zeroclass encompasses a fishing vessel, a PSV, and an SOV design, but more are on the way.

Image courtesy WavefoilWavefoil

Image courtesy WavefoilWavefoil

The recent buzz over wind-assisted ship propulsion has been hard to ignore. But one budding Norwegian company has devised an altogether different means of deriving ship power from the weather. The way CEO Bente Storhaug Dahl explains the technology is this. “Imagine you are trying to push a plank of wood down in the water, and it will spring back up. Now, imagine you angle the plank slightly forward, and you will see, the plank will spring up and forward.”

To this end, Wavefoil has come up with a new bow-mounted system of twin-foils, which fold out and back when not in use. Rather than provide extra drag, as might be expected, when the waves are high, the foils can perform two very significant functions on a ship. Firstly, they can add to the vessel’s stability, reducing slamming and spreading propulsion load, but they can also derive propulsive power from the waves themselves, generating a fuel saving of up to 15%.

The system is ideal for smaller vessels such as ferries and various type of workboats, particularly when operating in high sea conditions. It is easy to see where Wavefoil could work well in a Norwegian offshore context.

Norway-based gangway supplier Ulmatec has secured a contract for the supply of a 32-meter motion compensated gangway and logistics support systems for ECO Edison, the first U.S.-built Jones Act service operation vessel (SOV). Image courtesy Ulmatec

Norway-based gangway supplier Ulmatec has secured a contract for the supply of a 32-meter motion compensated gangway and logistics support systems for ECO Edison, the first U.S.-built Jones Act service operation vessel (SOV). Image courtesy Ulmatec

Ulmatec Handling Systems

Offshore deck equipment manufacturer, Ulmatec Handling Systems, is now busy building active heave-compensated gangway systems for the profusion of SOVs under construction at local yards. Visitors to the Ulmatec facility will be intrigued to see an imposing tower structure on the tarmac, used to test new gangway designs.

The aim is for walk-to-work gangway systems to serve other complementary purposes as well. For example, the company is developing telescoping gangways which can also serve as cranes, as well as housing extendable hoses, pipes and conveyors to transfer liquids and pallets to the turbine platform.

About two thirds of Ulmatec’s business is export, as it is supplying the new wave of offshore wind construction vessels which are serving the fledgling US market. Though it stipulates that the hull must be laid in a US shipyard, the Jones Act does not prevent Norwegian suppliers from equipping the vessels.

Meanwhile, things are heating up for another Ulmatec division, Thermal Solutions. Vessels can make better use of their waste heat, which comprises engine jacket water, exhaust gas heat, and other sources. Around 60% of the content of fuel is wasted in an internal combustion engine (ICE), said Bernt-Aage Ulstein, CEO of Ulmatec Pyro AS, which means that to make ships more efficient, that heat should be re-used for other purposes on the ship.

It is a future-proof business. “The electro-fuels, ammonia and methanol, will burn with less thermal efficiency than diesel and LNG do now,” Ulstein explained. “So it will be even more pressing to look at this.”

Bon voyage: a rendering of the adventure cruise concept, Sif, and its “refueller”, the thorium-powered Thor. Image courtesy Ulstein InternationalUlstein

Bon voyage: a rendering of the adventure cruise concept, Sif, and its “refueller”, the thorium-powered Thor. Image courtesy Ulstein InternationalUlstein

Family-owned shipyard Ulstein is no mere local legend, with its vaunted and immediately recognizable X-Bow having permeated the offshore and workboat fleet the world over. But the company’s new CEO, Cathrine Kristiseter Marti, admits that the yard has come through some tough times.

"We started to see light at the end of the tunnel at the beginning of 2020, and then COVID hit -- so no more cruise!” she says. “It is a buyer’s market. For us, it’s been quite the restructuring … we still deliver the same, but we are working with fewer people – 840 down to 400. Still, people rally together, and it is wonderful to see.”

The yard’s latest vessels are for Olympic Offshore, with two ships delivered early in July. Specialist vessels such as cable layers are a good fit for Ulstein, since they require in-depth technical knowledge not easy to replicate elsewhere.

Norwegian labour costs are unavoidably more expensive than in Asia or Turkey, but there are more benefits to think about, she explains, including being able to put new ships together at very low embodied carbon cost. “Norwegian shipyards operate on 100% hydropower… we think that should be valued.”

Meanwhile, Ulstein is excited about its latest project – Thor. It is a proposal for an offshore nuclear energy provider to feed SOVs or expedition cruise ships using molten salt reactor technology based on thorium.

Abundant in Norway, thorium could be used to power zero-carbon SOV operations or for battery-powered exploration cruise ships, enabling offshore charging in remote locations. Marti insists this is a change of pace for nuclear. “We will not be working with uranium, or other nuclear materials which can be turned into weaponry,” she said. “Ulstein is committing to that. That is why we are talking about thorium.”

Kongsberg Maritime

The drive to cut carbon emissions in ship construction is a key driver in Kongsberg’s R&D into additive manufacturing in metal, something which has eluded the industry so far. A consortium including Kongsberg, DNV, and several additive manufacturing specialists believe they have developed a new process, wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM), which can make parts stronger than ever before.

There are two technologies for this, MIG welding and plasma, both of which Kongsberg tested. The new part is a crank disc, which must be built to extremely high specifications. Kongsberg’s Mette Lokna Nedreberg, Manager of Material Technology, says that as well as potentially replacing costly and CO2-intensive traditional manufacturing processes, additive-manufactured parts fill a new niche, as well, in creating spare parts for deprecated machinery for which OEMs have ceased support.

“We very often have to buy new parts for our customers, and we wanted to see if we could 3D-print these,” said Ms. Lokna Nedreberg. “[Forging] uses a lot of energy and has very long lead times. But if the vessel is waiting for a component, they need it immediately.”

Meanwhile Kongsberg is continuing with the development of its permanent magnet rim drive thrusters, which can be used either as tunnel thrusters or for a steerable azimuth thruster.

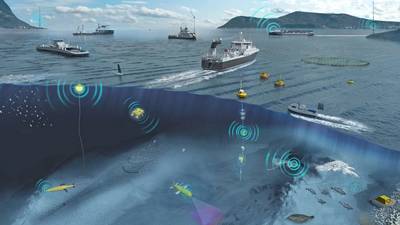

Photo credit: NTNUScanreach & Olympic Subsea

Photo credit: NTNUScanreach & Olympic Subsea

Another Norwegian offshore company with an agnostic approach to offshore renewables and oil & gas, Olympic Subsea has been working on turbines both above and below the waterline. Tidal turbines are a niche market, but various experiments are underway on the east coast of Scotland, as well as France and Japan. Despite abundant electrical energy to be harvested, one thing holding the technology back is the maintenance challenges. “We have to use a 250-ton crane, and there is a very narrow operational window, when the currents are low,” explains Marius Bergseth, COO of Olympic Subsea. “We can only do one tidal turbine each day.”

Olympic has been working with Scanreach, which has developed a means of keeping track of engineers embarked on wind turbines. A typical SOV may complete dozens of transfers per day, and Scanreach’s system can be used not only to keep track of them, but also to help Olympic calculate the optimal routes between turbines. “We have performed 225,000 transfers with gangways so far, without any incidents,” said Mr. Bergseth. “The wind park feature … serves as a list of where you have put the people, meshing all the wind turbines together,” said Arild Sæle, Scanreach CEO. “2.2km is the maximum distance between nodes, which is more than enough for most turbines.”

Green Yard Kleven

Building on the theme of shipbuilding with minimal CO2 emissions, Green Yard Kleven is inviting shipowners to rethink what happens when their ships reach the end of their lives. The yard has refitted many vessels, including distressed PSVs, to serve other purposes, including a yacht, as well as SOVs. This includes reconditioning equipment such as cranes and seismic arrays, the mechanics of which have not changed a great deal in comparison to their software, which the Yard helps to reprogram to be more up-to-date with current technology.

“The shipowners have said, ‘I don’t want garbage on my ship’, says Karl Johan Barstad, Sales Manager, Retrofit. But the response is different, he said, “… when we sat them down, and explained to them they could save 90% of costs, CO2 emissions …”

Green Yard Kleven has also implemented a new method for creating steel plate using lasers, which allows the yard to use less material – typically of 5mm thickness – than would be possible using conventional welding. While Norway no power player in green steel, Kleven can make good use of the available resources, wherever they happen to come from.