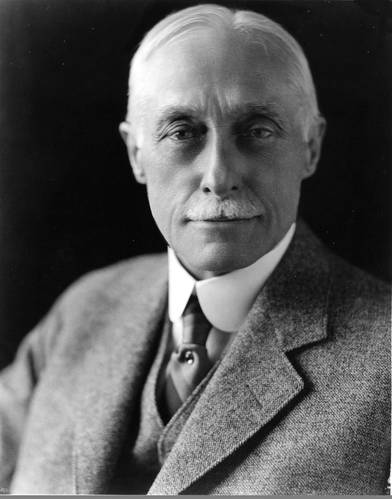

Elmer A. Sperry: Pioneer of Modern Naval Tech

Inventor, Entrepreneur, Industrialist & The Father of Modern Navigational Tech

Elmer A. Sperry casts a long shadow over the history of modern naval, nautical and aeronautical technology, one few people know much about, but should, for a man crowned both the “father of modern navigational technology” and “the father of automatic feedback and control systems,” as well as a pioneer of rocket and missile technology.

“It is safe to say that no one American has contributed so much to our naval technical progress,” eulogized Charles Francis Adams III, Secretary of the Navy from 1929-1933, on the death of engineering genius Elmer Ambrose Sperry, June 16, 1930, at 69.

Appointed to a newly formed Naval Consulting Board in 1915, Sperry spent the next decade working closely with the Navy, at times alongside his aviator son Lawrence (see related story, p. 38), developing gyro-compasses, stabilizers, autopilots, bomb sights, automatic fire control systems and powerful spotlights for ships and aircraft. Much of this technology was deployed by the Navy in both world wars, and continues to be used in some form on vessels of all sizes today.

“Harnessing the motion of the earth”

Describing Sperry as “. . . he who harnessed the motion of the earth to do his bidding. . ., the New York Times in an editorial on the day after his death, celebrated his achievements thusly:

“For those who travel by sea he provided not only the pilot who whatever betides hold his rudder true, but also a ‘stabilizer’ to prevent the rolling of the ship and a device for signaling to prevent collisions. For those traveling by air, he has helped to maintain the equilibrium of their planes and to lessen the peril of fire and to penetrate the fog.”

Sperry’s inventions, which often involved electricity and employed some form of control system, contributed greatly to advancements in lighting, mining, rail safety, street cars, brakes, engines, automatic ignition, automatic pilots, radar, guided missiles, drones and wireless systems. But if anyone deserves the epitaph “steady as she goes,” Sperry does.

The New York Times had it right when IT described Sperry as “. . . ever thinking of how he might make the dwellers on earth a little more at ease whether on sea or land or in the air.’’ In fact, his inventions, which typically focused on motion and energy, were all about creating, controlling, driving or directing movement. If it moved – whether it needed to be stabilized, navigated or powered, Sperry was on it. He even produced some of the earliest versions of electric cars, drones and remote controls – technologies that we are only beginning to scratch the surface of today he was experimenting with in the early 1900s.

Sperry even teamed up with physicist A. A. Michelson in 1922 to develop instrumentation to measure the speed of light. The value of the speed of light accepted by many today (299,792.5 km/sec) varies only 2.5 km/sec from that obtained using the Sperry octagonal steel mirror.

Many consider his contributions to inertial navigation to be the most important. Inertial navigation combines a computer, motion sensors and rotation sensors (gyroscopes) to continuously calculate via dead reckoning the position, orientation and velocity of a moving object without the need for external references. These systems are used in a range of applications, from transportation, i.e. submarines, ships, cars and planes, to guided missiles and spaceships.

“Inertial systems can sense direction and speed, and by inertia tell where the ship is going. It’s a perfect dead reckoning machine,” saID Craig Dalton, a professor of marine transportation at Massachusetts Maritime Academy.

Sperry’s ideas were often years, even decades ahead of his time. For example, his early work with autopilot for ships and planes is seen by some as predating the start of contemporary cybernetics – the scientific study of control and communication – pegged to the mid- to late 1940s by most accounts.

And while the U.S. Navy declined to pursue these avenues fully during the First World War, the “Sperry air bomb” and other efforts to control torpedo trajectory place Sperry among the earliest developers of drones and wireless control systems.

Inventor Rivaled Edison

A virtual nonstop inventing machine, Sperry collected or had pending close to 380 patents, twice as many as Thomas Edison at the time of his death (and Edison went on to hold the record for most patents granted to an American). Sperry was also a prolific entrepreneur, founding eight companies along the way.

Sperry was a man of his age – an era when the inventor-entrepreneur first came into play. Some, like Edison and Henry Ford, created whole new industries and manufacturing empires with their inventions. Others, like Sperry, while certainly interested in profit and successful financially, were drawn more to the science involved and the opportunity to apply new technologies and mechanics, according to his biographer, Prof. Thomas Hughes Park, author of the highly referenced Elmer Sperry – Inventor and Engineer. He was forced to sell off his first company, the Sperry Electric Light, Motor, and Car Brake Co., which he founded in 1880 at the age of 20, five years after its founding. The experience proved a lesson to Sperry. He wasn’t interested in being at the beck and call of other people’s assignments, or as much in the business of running a company, as he was in having the opportunity to explore new technologies and innovate, and the chance to tackle problems of his choosing. All of which led him to launch one of the country’s first research laboratories in 1888.

What Sperry is known most for is the gyroscope and its application to many problems, most notably in his version of the gyrocompass, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg of the man’s inventions and interests.

He was among a handful of inventors toying with electric cars in the late 1800s, winning patents for combustion engines (later adapted to aircraft engines), automatic transmissions and electric brakes, street cars and automobiles, as contemporaries in England and Germany produced vehicles for sale, and electric cab companies buzzed onto the scene on both sides of the Atlantic. But the concept was doomed, both by the unreliability of rechargeable electric batteries and the mass production of gas-powered cars at half the cost of electric.

That state of affairs would prove fortuitous for other modes of transportation – notably ships and planes, the latter another emerging – and more successful – technology in the late 1800s to early 1900s.

Sperry’s early interest in electricity – which he dropped out of Cornell after a year to pursue – was eventually overtaken by his fascination with gyroscopes and gyrocompasses. He neither discovered these concepts, nor was he the first to market with patents. That was German Hermann Anschütz-Kaempfe, who was awarded a gyrocompass patent in 1906 in the U.K.

Sperry could barely contain his enthusiasm at a 1908 meeting of the Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers (SNAME), telling the gathering, “The marine interests may certainly expect great and material aid from this wonderful instrument. Not only, I predict, will it guide our ships, but it will be found to have other important and far-reaching bearing upon the operation of ships at sea.”

Sperry’s approach in general was to expand upon and further advance existing applications, which he particularly applied to gyroscopes. For example, by 1907, Sperry was working on the issue of stability in moving vehicles. He took gyrostabilizer technology already in existence – it fostered stability by pushing rolling ships in the opposite direction of the force of the waves – and added a motion sensor, a motor to amplify the effect of the sensor on the gyroscope and an automatic feedback and control system. The net result was a better performing stabilizer. He followed that up with his improvements on existing gyrocompass technology.

His timing was perfect.

The gyrocompass was immune from deviation and variation problems, which had been difficult to overcome, particularly in the huge steel warships that the Navy was starting to turn out. According to Sperry Marine’s corporate history, three things drove the transformation of the gyroscope from a curiosity to a usable technology. “These were the increasing use of steel in ships which then brought about the second need: to overcome the unreliability of the magnetic compass within a steel ship, and finally, the great powers were preparing to conduct underwater warfare – in steel hull ships.” A fourth variable was also key – an electronically driven gyroscope invented by G.M. Hopkins would enable the gyroscope to act as a reliable reference device in those steel ships.

Gyroscopes and Gyrocompasses

As described by MIT, a gyroscope is a disk mounted on a base in such a way that the disk can spin freely on its X- and Y-axes; that is, the disk will remain in a fixed position in whatever directions the base is moved.” A gyroscope will always point to a fixed point in space if left undisturbed. If force is exerted upon it, it will react at right angles to the force applied. This characteristic combined with other elements of precession, pendulocity and damping will allow the gyro to settle toward true north.

A gyrocompass incorporates a gyroscope and is a non-magnetic compass that uses a fast-spinning disc and the rotation of the Earth to automatically find geographical direction, or true north.

“A gyroscope is for stability purposes; a gyrocompass is purely for navigation,” said Dr. Josh Smith, a professor at Kings Point. “The original gyrocompass stood four feet tall at several 100 pounds and was used by the mate in charge of the watch. Now it can fit in the palm of your hand.

At the same time Anschutz-Kaempfe, who was seeking a reliable form of navigation for a submarine expedition to the Artic Pole, was patenting the first north-seeking gyrocompass, Sperry in 1908 received a patent for his version of the gyroscope. Sperry filed a patent the first ballistic gyrocompass 1911 (which he received in 1918 in the U.S.) and set about with his son Lawrence, trying to sell it to the U.S. Navy and others abroad.

Initial disinterest by the U.S. military led Sperry to successfully pitch his technology to Japan and Russia. Eventually the U.S. Navy came around and adopted his compasses and stabilizers in 1911 after successful trials on the USS Delaware and USS Drayton - as did the French, British and Italian Navies.

The Navy also began using Sperry’s gyroscope-guided autopilot steering system, variously called a “Metal” or “Iron” Mike.

“It was a big manpower saver because you didn’t need a helmsman,” said Dalton. “I had captains when I sailed who did not want seamen on the wheel because the autopilot used less fuel. Many captains believed the autopilot steered better than men.”

The Drayton trial produced the repeater compass and the target-bearing pointer. This was followed by a request from the Navy to examine the fire control problems faced by ships bearing long range guns.

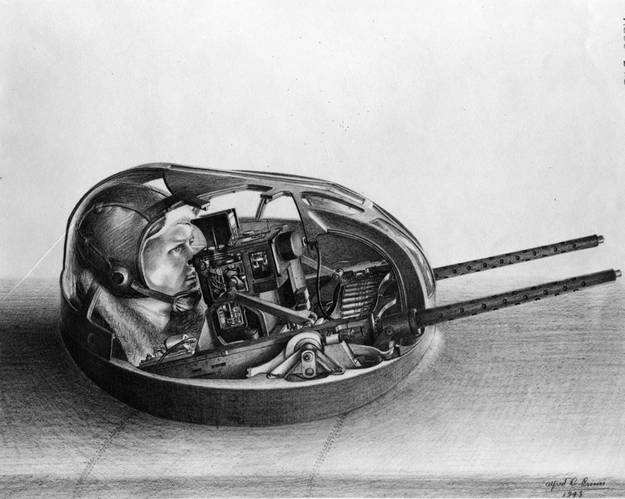

Ship gun fire-control systems (GFCS) enable remote and automatic targeting of guns, with or without the aid of radar or optical sighting. Sperry developed the first full gun battery fire control systems, which were placed aboard every U.S. battleship during World War I.

Before the advent of the fire control systems, if a gunner aimed a gun and the boat pitched, his gun would end up pointing in the water. But Sperry gave the gun mounts turrets that prevent the ship’s pitch from interfering with the trajectory of the gun.

Sperry also provided the Navy with a 5-ton device called a gyro stabilizer, designed to keep ships from rolling, The Navy installed it on the USS Worden, and another one on a submarine. The onset of WWI put further orders on hold.

In 1910, Sperry started the Sperry Gyroscope Company in Brooklyn to sell his inventions, locating near the port of New York so ship captains could easily visit his factory.

Among the projects the company worked on during World War I was an autopilot for airplanes, gunfire control systems, machine guns that could easily track their targets, bomb sights and gyroscopically-guided aerial torpedoes. Like so many of his earlier inventions, these often relied on automatic control and feedback systems. In 1918, he produced a high-intensity arc lamp that had an unheard of brilliance equal to that of a billion candles. It was used as a searchlight by both the Army and Navy, and helped to fend off German air raids on London and Paris.

In the midst of all that activity Naval Secretary Josephus Daniels launched the Naval Consulting Board in 1915 with the help of Thomas Edison to put the brightest minds of technology and science to work for the war effort. Sperry was tapped as part of the inaugural crew and went on to lead several committees, and eventually held the chairmanship. It was there he and his son Lawrence teamed up with Peter Hewitt to develop the Hewitt-Sperry Automatic Airplane, a so-called “flying bomb” and one of the first successful precursors of unmanned aerial vehicles, or as they are called today, drones. It is considered by some to be a precursor of the cruise missile.

“Torpedos never were especially accurate. A gyroscope helped keep them running straight and true,” according to Kings Point’s Smith.

Also in 1915, Anschütz-Kaempfe slapped Sperry with a patent lawsuit over his gyroscope technology after Sperry attempted to sell his gyroscope to the German Navy. Anschütz-Kaempfe retained as an expert witness, a young Swiss patent office employee named Albert Einstein. In a trial that dragged out over two years, Einstein shredded Sperry’s defense, and Anschütz-Kaempfe won the lawsuit in Germany. Sperry, however, prevailed with his patent in the U.S. and the U.K.

After the war, one of Sperry’s last accomplishment came in September 1929, when Sperry engineers working with the U.S. Army Air Corps, developed and successfully tested two new capabilities – the artificial horizon and the aircraft directional gyro – recording the first all-blind flight in history. The technology was quickly adopted by commercial airlines and installed aboard mail planes.

An Iron Legacy

The reach and enormity of Sperry’s contribution to naval science, offensive weaponry and the navigation and control of transports on water and in the air, cannot be overstated. It stretches well beyond his lifetime and is still working to aid sailors, pilots and the military around the globe.

Sperry, once a member of countless technical and scientific societies, was the recipient of numerous awards and honors.

In 1941 the Navy christened the USS Sperry (AS-12) in his honor, while the Post Office introduced an airmail stamp in recognition of the contributions of both father and son to flight.

Today, there are a number of awards given out in his name, including one from Northrup Grumman given to a U.S. Naval Academy midshipman every year, one from Honeywell and the Elmer A. Sperry Award for “advancing the art of transportation engineering,’’ given out by a consortium of societies he once belong to.

According to Sperry biographer Hughes, among the many upon whom the inventor made a great impression was Helen Keller, no stranger to fame and admiration herself.

Sperry went out of his way to “show” her how the gyroscope worked, the movement of the compass and the brightness of the arc lights.

A “wonder-filled” Keller summed it up best when she said she thought Sperry would be remembered for a compass and a star for “if there were no other immortality, you would live forever in that achievement.”

And so he will.

Sperry’s Patents

Elmer A. Sperry was a man of wide ranging interests and ideas, delving into areas ranging from electricity to navigation, to automation to motion control and missile guidance, to even the more mundane, such as his golf bag support (patent #1,686,774) – to name a few. Along the way, he founded at least eight companies and two technical societies, served on countless boards and industry and technical associations, and collected an estimated 380 or so patents. What follows is a sampling of Sperry patents that have enhanced and influence maritime technology over the last century or so:

NAVIGATION:

Ship Gyroscope (Filed 1908),Ship Gyrocompass (Filed 1909), Gyroscopic Navigation Apparatus, Navigational Apparatus, Navigational Instruments, Repeater System For Gyrocompasses, Electric Drive For Gyroscopes, Controlling Mechanism For Ships Gyroscopes, Gyroscopic Pendulum, Control Gyro

STABILIZATION:

Gyroscopic Apparatus For Determining Periodic Motion, Gyroscopic Stabilizer, Stabilizing Gyroscopes, Multiple Gyro Ship Stabilizer, Ship Stabilizing And Rolling Apparatus, Gyroscopic Roll And Pitch Recorder, Means For Preventing The Pitching Of Ships

DEFENSIVE:

Various Patents For Detecting, Tracing, Locating And Signaling Submarine Boats, Anti-Aircraft Systems

AIRPLANES:

Speed And Direction Indicator, Aeroplane Stabilizer, Position Indicator, Automatic Pilot, Automatic Sighting Mechanism For Aircraft Guns, Gyroscopic Inclinometer, Beacon System For Night Flying, Automatic Steering For Dirigibles, Variable Pitch Propeller, Automatic Launching Device For Airplanes (!127)

WEAPONS:

Driving And Governing Means For Torpedoes, Electrical And Gyroscopic Apparatus For Torpedoes, Automatic Gun Pointing, Multiple Turret Target Indicator, System Of Gunfire Control, Submarine Mine, Wireless Controlled Aerial Torpedo, Gravity Bomb, Wakeless Torpedo, Bomb Site, Fire Control System. Method Of Gunfire Control For Battleships, Automatic Accelerator, Automatic Steering (1926)

OTHER PATENTS OF NOTE:

Multiple Patents For Power Gearing And Controllers For Electric Cars (Filed 1984-1896), Electric Vehicle – (Filed 1898), Wireless Control System, Electrical Arc Light, Signaling System For Warships, and engines of all kinds.

Sperry’s Companies

Inventor-entrepreneur Elmer A. Sperry was fond of launching new companies to manufacture new inventors and support his wide ranging interests, at times folding, morphing or selling off older companies even as he was forming new ones. He is perhaps most closely associated with the Sperry Gyroscope Co.:

• Sperry Electric Light, Motor, and Car Brake Co., founded at the age of 20 to manufacture Sperry’s electric dynamos and arc lamp invention. (1880)

• Sperry Electric Mining Machine Co. (1888)

• The Elmer A. Sperry Co., for research and development work (1888)

• Sperry Streetcar and Electric Railway Co., for electric streetcars and their components (1894)

• Chicago Fuse Wire Co., (1900); and separately established an electro chemical laboratory in Washington, DC. , where he discovered a process for recovering tin from scrap metal.

• Sperry Gyroscope Co. (1910), founded to manufacture navigation equipment, chiefly his own inventions – the marine gyrostabilizer and the gyrocompass. During World War I the company diversified into aircraft components, such as bomb sights, fire control systems, airplane stabilizers and autopilot.

• Sperry Development Co. (1926), Sperry Products Inc. and Sperry Rail Service - all associated with his rail detector and diesel engine products.

The Sperry companies that remained, including the Lawrence Sperry Aircraft Co., eventually became the Sperry Corp. several years after the deaths of both Elmer Sperry and his son Lawrence, with the maritime sector spinning off into Sperry Marine in 1997, which eventually became part of Northrup Grumman Corp., a worldwide supplier of navigation, communication, information and automation systems for commercial marine and naval markets.

Also a member of many engineering, aeronautical, maritime, industry and other scientifically-oriented organizations, Sperry founded at least two:

• Founder and charter member of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers

• Founder and charter member of the American Electro-Chemical Society

He was also an inaugural member and eventual chairman of the U.S. Naval Consulting Board, which was formed in 1915 by the Secretary of the Navy with help from Thomas Edison.

(As published in the May 2014 edition of Maritime Reporter & Engineering News - http://magazines.marinelink.com/Magazines/MaritimeReporter)