Vessel Ordering Mania – Why?

The flood of interest in ordering new container vessels is motivated by other factors than supply and demand.

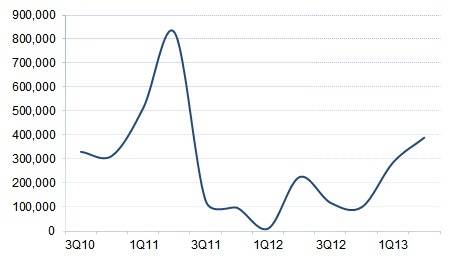

The recent surge in new vessel orders at a time of industry-wide overcapacity suggests that market fundamentals are no longer the main driver (see figure). Even when the most recently ordered ships are delivered in 2016, Europe and the US are still likely to be climbing out of recession, which means that capacity in the east-west trades will continue to outstrip demand.

One of the factors behind the surge in orders is plummeting shipyard prices. Smaller carriers now see an opportunity to gain a competitive edge over the big three at last, and have not been slow to take advantage of it. For example, CSCL’s recent order for 5 x 18,400 teu ships, the first of which is due for delivery in 4Q 2014, each cost $136.6 million, approximately 26% less than Maersk’s 20 x 18,000 teu vessels, which were ordered in 2011, with the first being named only two weeks ago.

The comparison is not exact, as there is a difference in design specification. Maersk’s hull is twin screw, whereas CSCL’s has only one propeller, and Maersk’s vessels also have expensive on-deck cell guides to facilitate cargo operations and improve safety.

The big advantage of the 18,000 teu vessels is their fuel consumption. Compared to the 13,000 teu ships ordered by competitors, they are claimed to burn around 35% less per container. As fuel accounts for well over half of all voyage costs, it is easy to see why new market entrants can be lured in, including UASC, which is reported to be discussing the price of five of the giants with an Asian shipyard.

UASC has also expressed interest in ordering four 14,000 teu vessels. In this respect OOCL ordered six 13,000 teu vessels in 2011, each costing $136 million, and NOL ordered 10 x 14,000 ships in 2011, costing $154 million, including the upgrading of 10 8,400 teu vessels, whereas Seapan’s order for five 14,000 teu vessels in March 2013 are estimated to have cost just $108 million each. The price of K Line’s five 14,000 ships, which were fixed shortly afterwards, is not known, but will have been little different.

Getting credit for such orders is still not difficult, strangely, despite the ships not always being ordered to meet demand growth. However, the credit is selective for certain companies and ship types. Also, with many ocean carriers being state-supported in some way, banks appear to see their loans as being as good as sovereign debt, so not high risk, even though the current surplus of vessel capacity is already destroying profitability through swinging freight rate decreases.

This means that maintaining the cash flow required to service ship mortgages is increasingly difficult for carriers. Cash-rich non-owner operators, such as Seaspan, Costamare, Technomar, and Capital Ship Management, clearly see this problem worsening, which explains why they have returned to the market in a big way, providing another factor behind the surge (see table).

They have also been using their cash advantage to help owners acquire specialist tonnage, such as the wide-body vessels now favored in South American schedules.

So, even where borrowing to fund newbuilds becomes too difficult, carriers will be able to circumvent the problem through leasing or chartering. The container industry, it seems, remains dominated by optimists.

According to Drewry, non-operating owners clearly expect that, as ocean carriers’ cash flow gets tighter, the charter market will increasingly be used for newer fuel-efficient vessels, including the wide-bodied 8,000/9,000 units currently gaining currency in South America.

drewry.co.uk