Offshore Wind: California's New Gold Rush

California Dreamin': In CA, offshore wind has unlimited potential

When it comes to States promoting renewable, non-fossil electricity generation, California surely leads the list, from utility-scale regional grids to individual rooftop solar panels.

In fact, a December 2018 update from the California Energy Commission (CEC) estimates the state may already have exceeded an initial renewable generation goal of 33% by 2020. CEC estimates that in 2018 that generation number was already 34%. You can note (below) that wind accounted for 29% of the almost 100,000 GWh of renewable electric generation in 2018.

None of those 27,838 GWh comes from offshore wind – yet. As in other states, CA’s offshore wind is still to come, still on the horizon; or more likely, just over the horizon, keeping wind towers out of sight from CA’s postcard shorelines.

It’s important to note that unlike some Atlantic coast states, e.g., New York, California has not set a specific demand for offshore wind. In CA, offshore wind will result from merchant projects, not utility policies. But, of course, this is California, with an almost insatiable demand for electricity – especially as electric vehicles are mainstreamed. If you have renewable energy to sell, CA’s buying.

CA’s offshore wind could be an energy gusher. In 2016 DOE’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) published a study: “Potential Offshore Wind Energy Areas in California: An Assessment of Locations, Technology, and Costs.” One conclusion: CA’s offshore wind resource potential “corresponds to about 1.5 times the state’s electric energy consumption based on 2014 EIA figures” (italics added, EIA = the US Energy Information Administration). The NREL study is based on six likely Pacific wind energy areas, from Crescent City, in the north, near Oregon, to Port Hueneme, just north of LA.

CA’s offshore process started in earnest three years ago when a wind energy company then called Trident Wind – now Castle Wind – submitted an unsolicited request to BOEM (Bureau of Ocean Energy Management) to lease a site in the Pacific near Morro Bay (about half-way between LA and San Francisco).

Castle’s filing started a federal-state effort to determine best ways to move forward. Officials from the California Energy Commission teamed up with BOEM to form the California Intergovernmental Renewable Energy Task Force (Task Force) which first met in October 2016.

After Trident’s “nomination” – that’s BOEM’s term for when a company suggests or proposes a project – BOEM issued a request for comments (referred to by BOEM as a “Call”) on the merits of the Morro Bay site and to check competitive interests, i.e., to check for “nominations” from other wind energy companies.

Indeed, Equinor responded with interest in Morro Bay – an important signal regarding markets and project viability, not just for CA ratepayers but also for US taxpayers since Uncle Sam collects rent from the leased sites. In September 2018, BOEM received another unsolicited nomination from the Redwood Coast Energy Authority (RCEA) for a possible project in the Humboldt Bay area (near Eureka, CA).

Last October BOEM issued a Call with a broader scope, focusing on three Outer Continental Shelf sites (which were within the NREL study referenced above): the Humboldt Call Area off the north coast and the Morro Bay and Diablo Canyon Call Areas, both off the central coast. These areas cover approximately 1,073 square statute miles (687,823 acres). Comments – and nominations – were due January 28, 2019.

Indeed, there is strong demand for Pacific wind energy areas (WEAs)! BOEM received nominations from 14 companies expressing interest in all three proposed areas.

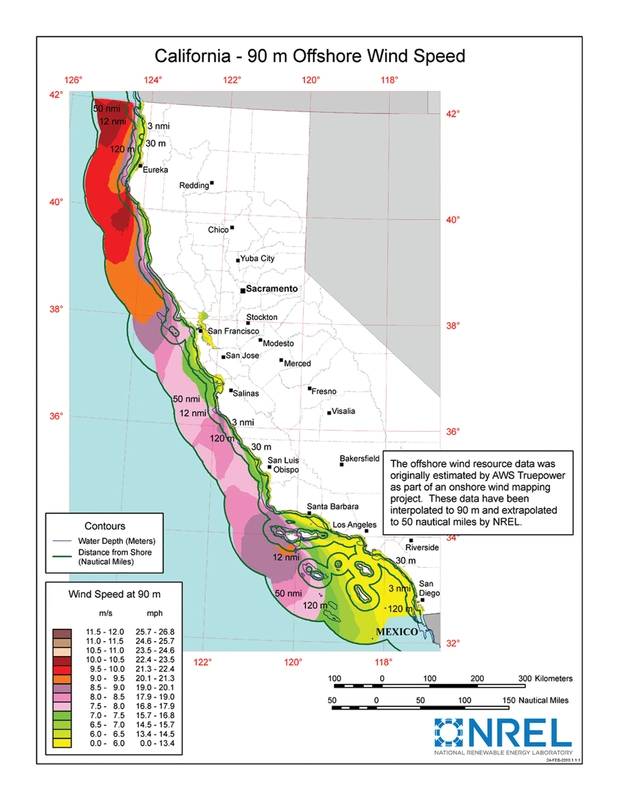

The California offshore 90-meter (m) height wind map and wind resource potential estimates are provided on this page. Areas with annual average wind speeds of 7 meters per second (m/s) and greater at 90-m height are generally considered to be suitable for offshore development. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory has produced these estimates of the gross (not reduced by environmental or human use considerations) offshore wind potential expressed in "installed capacity." This is the potential megawatts (MW) of rated capacity that could be installed at offshore areas with mean annual wind speeds of 7 m/s and greater at a 90-m height, assuming 5 MW of installed capacity per square kilometer of water. The offshore wind potential tables PDF present the resource broken down by annual wind speed, water depth, and distance from shore. (Source: NREL)

The California offshore 90-meter (m) height wind map and wind resource potential estimates are provided on this page. Areas with annual average wind speeds of 7 meters per second (m/s) and greater at 90-m height are generally considered to be suitable for offshore development. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory has produced these estimates of the gross (not reduced by environmental or human use considerations) offshore wind potential expressed in "installed capacity." This is the potential megawatts (MW) of rated capacity that could be installed at offshore areas with mean annual wind speeds of 7 m/s and greater at a 90-m height, assuming 5 MW of installed capacity per square kilometer of water. The offshore wind potential tables PDF present the resource broken down by annual wind speed, water depth, and distance from shore. (Source: NREL)

Concurrent to BOEM’s Calls, the BOEM/CA Task Force has been in a developmental mode – meeting with stakeholders, creating a new California Offshore Wind Energy Gateway to facilitate development and documenting and presenting how wind energy could impact coastal, fishing and tribal communities.

This outreach is important. Offshore wind in California is much more difficult than the “average” ocean-based wind project. The Pacific Ocean slopes off more suddenly from the shore compared to the Atlantic coast, getting deep very quickly.

Pacific projects will require wind turbines built within or on floating platforms, cabled to the ocean floor, possibly in waters 800-1000 meters deep. An area with dozens or hundreds of floating platforms becomes a very different seascape, laced with underwater cabling, both for infrastructure stability and power transmission. Some of that submerged cabling infrastructure will extend for miles, from offshore platforms to landside connections.

This demands a close look at marine and maritime impacts. The Pacific Merchant Shipping Association, for example, recommends that BOEM, upfront, eliminate WEAs that overlap with shipping lanes. PMSA Vice President John Berge advises that this would “avoid wasting unnecessary time and resources pursuing projects that conflict with maritime traffic routes.”

Floating platforms are not yet in widespread use. However, wind energy companies believe these platforms, in various configurations, are on the cusp of being market ready.

There is one project – called Hywind, built by Equinor – in Scotland using platforms; it’s small, just five turbines. Equinor is one of the companies which responded to BOEM’s Call. Equinor writes that it will utilize the “competence, lessons learned, and experiences gained from these Hywind projects in the development of larger scale floating projects in California.”

Some companies are working together to build an offshore project. In the Humboldt Call Area, for example, the Redwood Coast Energy Authority (RCEA), a consortium of local governments, has been working to develop a wind project since 2017. Humboldt Bay has some of the best Pacific wind resources, although that is offset by challenges with land-based connections.

RCEA selected an energy team that includes Principle Power Inc. (PPI), founded in 2007 in Emeryville, CA. PPI has developed the WindFloat, a floating foundation for offshore wind turbines, being readied for operation in Europe in 2021. RCEA also selected Aker Solutions, the Norwegian company expert in oil and gas platforms. RCEA’s third partner is EDPR, Portugal’s largest generator, distributor and electric supplier and the fourth largest operator of wind energy based on net installed capacity in the US.

BOEM and CA Task Force officials were to update their activities since the December Task Force meeting and the close of the comment period, January 28, for BOEM’s October Call.

John Romero, a BOEM public affairs officer, said BOEM has reviewed 118 public comments, which cover a range of opinions about offshore wind: strongly supportive, supportive but cautionary, and, of course, some in opposition.

A CA Task Force spokesperson said staff continues to work on “outreach, data collection and working with state and federal agencies.” Regarding development of a wind energy supply chain, like in NY and Virginia, the spokesperson said, “it’s too early in the process” to focus on that.

The BOEM/Task Force work, of course, is preparatory. In reality, all of this background work positions BOEM to officially start its prescribed wind energy evaluation process. BOEM’s next task is “area identification,” likely taking about six months, then come decisions about specific areas, taking another 18 months. BOEM anticipates conducting a lease sale in 2020. Site assessments and surveys and technical reviews, taking 6 – 7 years, would follow a lease sale. Project work could start after that.

Six or seven years, of course, is a long time for a business to have to keep the faith among investors, employees and suppliers that a good idea will – eventually – come to fruition.

John Romero was asked whether his team senses impatience about a schedule that, after three years, is just now at the starting point. Romero concurred that this is not a quick process, but he added that people in energy businesses know that BOEM has to work equitably and transparently among all parties. He said that President Trump’s recent Executive Order on regulatory streamlining is causing a fresh look at ways to work faster.

Alla Weinstein is CEO of Castle Wind, a joint venture with EnBW North America. Recall it was Weinstein’s WEA lease request, in 2016, that started BOEM’s CA activities. Weinstein was asked for her perspective on BOEM’s timeline and timeliness.

“We believe BOEM is moving as fast as they can, realizing that the creation of an offshore wind industry in California requires significant time and investment,” she said, noting the “unprecedented number of agencies and stakeholders” involved. She pointed out that wind farms will be installed in federal waters, but interconnection and affiliated activities are under state and even local jurisdictions.

Weinstein was asked about alignment between regulatory timelines and private sector challenges regarding financing, project planning and a business plan. “Of course, we’d like for the process to move as quickly as possible,” she said. “The sooner we can begin development and truly launch the offshore wind industry, the sooner we can help contribute to California’s clean energy mix and begin to bring costs down. Not to mention the local and regional economic benefits that these new projects will drive.” She would like to see an auction in early 2020, a date that lines up with BOEM’s schedule.

Still a lot of work ahead. But now the focus starts to change: it’s no longer whether there should be offshore California wind energy. Rather, it’s figuring out the best ways to make it work. Remember, things happen first in California.