Search and Rescue Tech. Oceania

A human silhouette is outlined by the light of a cell phone as theater patrons shift their attention toward the disturbance. The user’s eyes scan messaging with expression of concern, reading of a boating accident and a lone mariner’s single call for help. This story begins as a first responder moves towards the green exit sign, departing his liberty to join an assembling sortie.

Standing the Hawaiian Islands watch requires a force of on call specialists, always ready for the surge capacity nature of the job. Modern search and rescue (SAR) methodology has sprinted forward in recent decades, keeping pace with evolving technology. Sometimes a Coast Guardsmen’s best lifesaving tool is not only more than two hundred years of lifesaving tradition, but also products of the digital era.

A few miles offshore a man drifts in the darkness, suspended above the sharply sloping seafloor by a sun faded lifejacket. His imagination conjures fantasy on what lurks the depths below, and his mortality hangs on the edge of every moment. Was his call for help ever heard? He stares longingly at the ascending light of Honolulu.

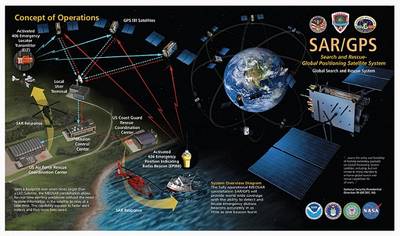

Without a radio, he has no way of knowing that his call was heard and the transmission’s source identified. The Coast Guard’s Rescue 21 system uses radio communication towers to create lines of bearing, triangulating the origin of VHF radio transmissions. With Rescue 21, a single mayday call can pinpoint vital coordinates, and sometimes you only get one call.

Beyond the Earth’s atmosphere, another technology comes into play. A passing satellite detects the distress call of an electronic position indicating radio beacon (EPIRB). These registered signal devices are activated either manually or when submerged in salt water, a process called hydrostatic release. Personnel at the Coast Guard Joint Rescue Coordination Center Honolulu start feeding information on the device’s owner to the Coast Guard’s Sector Honolulu Command Center where the case is being managed. They know who he is, where he lives and how to contact him.

The command center continues to ramp up with intelligence and activity. News networks begin calling in with requests for names, causes and outcomes. Police, fire and Honolulu Ocean Safety are coordinated to help where they are able. With the registration information from the EPIRB, watchstanders contact the man’s family to verify that he got underway alone. They confirm that the coordinates identified by Rescue 21 are in agreement with the EPIRB signal and search pattern areas are being drawn up with supreme confidence.

The distant hum of a helicopter’s blades gives hope to the lost mariner. The aircrew arrives less than a mile away, deploying a self-locating data marker buoy, which will follow currents while signaling SAR assets on scene. This signal allows rescue crews to understand where a person in the water may be drifting.

The mariner rationalizes that his call was heard, but knows that without a strobe light or signal flare, he hasn’t been spotted. Even as the recently quiet sea comes to life with fast response boats and spotlight beams that sweep the darkness, he understands that what he is seeing is a large search area in the vicinity of his capsized vessel, now more than a mile away.

At the command center, personnel are familiar with the science of drift, and another system is already collating this data. To calculate search areas in the complex currents of the Hawaiian Islands, watchstanders use the Search and Rescue Optimal Planning System (SAROPS), a software system that uses simulated particles generated by users in a graphical interface. These particles are then influenced by environmental data to provide information on search object drift. Using information on a point of origin and local currents, it calculates the most likely area to find a person in the water.

With SAROPS updating the search areas, it isn’t long before the man observes a search light honing in on the floating debris that surrounds him. Soon a hand is reaching down and two young crewmembers hoist him aboard. Everything feels surreal as the weight of gravity returns to his exhausted limbs. A woman is yelling, “Are you injured? Were you alone?” He stammers in a state of shock, “I was alone. I think I’m ok.” In a state of shock he is silently fascinated by the intent and deliberate effort of his rescuers as they secure the deck.

As the SAR machine of personnel and technology is ramped back down, this fictional story comes to an end. It is a simple example, and a best case scenario. In just a few more hours he could have drifted into a “needle in the haystack” scenario, lost in the 60 million square mile Pacific Ocean. The Coast Guard’s 14th District encompasses more than 12.2 million square miles, shared operationally by JRCC Honolulu, Sector Honolulu and Sector Guam command centers.

To the east and west, Hawaii is separated from the world by a vast and open ocean. The Hawaiian Islands themselves are actually the tips of the tallest mountains in the world. Within this wilderness a completely different SAR approach can be required. For cases outside the immediate reach of response assets, a system called AMVER is coordinated through JRCC Honolulu.

Originally the Automated Merchant Vessel Emergency Reporting system, AMVER evolved into a global technology over the past century. It relies on the cooperation of commercial mariners to assist others in need. When a vessel is found to be in distress, registered AMVER vessels in the area are contacted to provide assistance. With its roots reaching back to the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, AMVER now incorporates cutting edge satellite and communication technologies as a critical lifesaving tool in the modern maritime community.

At the crossroads of life and death, no outcome is a certainty. To a soul lost at sea, first responders are usually the mariner’s last hope, and for every story of heroic rescue, there are is an equal of tragic demise. Even with all the state-of-the-art SAR technology in existence today, nothing can ensure survival at sea more than a skilled and well prepared mariner.