Mitigation of Shock & Vibration on Fast Boats

Repeated Shock and Whole Body Vibration Awareness

For some time now, military agencies and specialist organizations around the globe have driven the evolution of high speed watercraft. As a trickle-down effect fast response craft now serve roles once typically serviced by displacement designs including pilot boats, dive boats, crew boats and offshore support. During high speed operations the repeated shocks (RS) and whole body vibrations (WBV) of this harsh environment are transmitted to the passengers, operators and crew aboard, creating avenues of owner liability if not addressed.

While economic considerations and fast transport of personnel are core commercial objectives [1], long term exposure to RS & WBV pose health risks to personnel. Quantitative evidence from military studies indicate that high-speed boat crews have a hospitalization rate that compares to construction workers [CN], firemen [FN] and air crews [AN] within the military community [3]. Self-reported injuries among US Navy special operations crews reveal the extreme nature of the environment. Of those surveyed, 64.9% reported at least one injury [3]. Some operators reported multiple injuries. Typical of high speed craft operators, injuries ranged from sprains & strains to chronic pain and severe stress fractures [3]. Other studies indicate the rate of injury on board U.S. Navy high speed craft is six times the overall U.S. Navy average [5]. A large percentage of those are acute and chronic lumbar spinal injuries presenting both immediate and long term ramifications to the effected crewmen [6].

Most waterborne injuries can be placed in the category of “motion induced” caused by the human body’s reaction to the physical work associated with self-mitigating the shocks during transit [4]. Motion induced fatigue is more clearly defined as physical impairment that results from exposure to WBV and RS for long periods of time, including deficiencies in vigilance, perception, decision-making and reaction time. General discomfort, fatigue, post-transit degradation of performance and motion sickness when operating at low speeds are also among the wide spectrum of issues associated with motion induced fatigue [2].

As the exposure effects to extreme motions and repeated high acceleration slam impacts in high speed craft are becoming better known, increasing operational capabilities facilitated by enhanced watercraft designs no longer means that the vessel is simple to operate within the full operational envelope. Awareness of these issues have compelled specifiers and designers to consider best design practices of shape, form, function, ergonomics and seating solutions to counter the physical stresses that shock and vibration energies impart to the crew and passengers.

The roles of passengers also increasingly need to be considered by boat crews as they are being transported and perform tasks both at speed and once on-station [1]. Passengers will benefit from having a pre-voyage briefing - knowing what to expect and how to act in reducing their potential for injury.

As on-board systems become more complex the competencies demanded of operators move to a higher level and are more like those required by a helicopter crew where effective situational awareness and command & control become crucial for performance and safety. With new and retrofitted craft being capable of out-performing the crew it is essential that designers focus on human factors to ensure that they can operate the craft at the edge of its operating envelope and still ensure operational success and safety for the crew and passengers [1].

Reducing RS and WBV experienced by boat crews by slowing down, better training, and novel hull designs is widely recognized, but a great deal of research in the area of shock mitigation, has revolved around seating systems [7]. Notwithstanding the boat’s structural limits, shock mitigating seats are also easily retrofitted onto existing watercraft to effectively upgrade the operator’s environmental operational envelope.

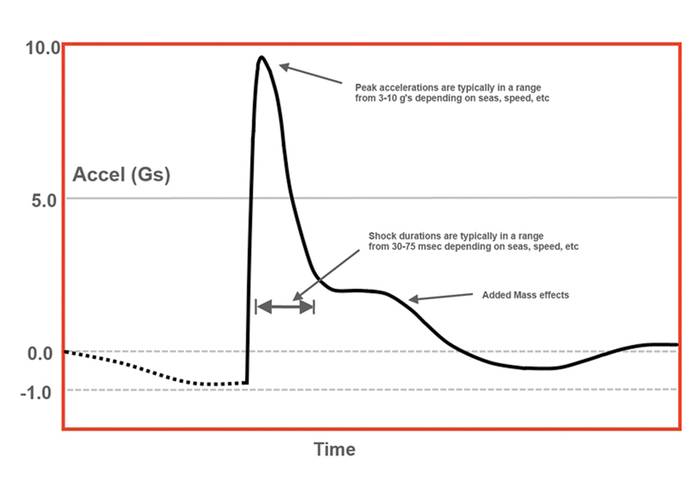

The variability in operating conditions and human factors makes it difficult to design an ideal shock mitigating suspension system [4]. High Speed Craft (HSC) seat suspension design places unique challenges on manufacturers due to the diversity of maritime operating conditions. Fast craft can, on the same voyage, experience variations from calm seas at harbor, to potentially violent rough waves away from shore. Current automotive suspension systems are not appropriate for use in marine seats. For example, the sprung mass in automotive applications remains relatively constant when compared to marine seating, which can vary 300% or more. Similarly, ranges of environmental inputs in automotive applications are not comparable considering the extremes of sea conditions. As a result, approaches to marine seat design differ greatly from other vehicles.

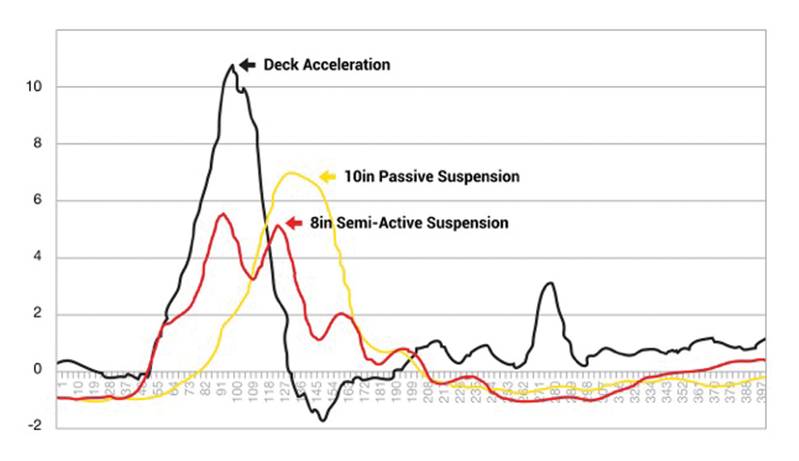

Most shock mitigating seat designs currently use a passive suspension system to absorb the shock transmitted through the hull. Even the most advanced passive suspension systems can only be tuned for a relatively narrow range of conditions to operate effectively. Typical occupant weight and sea state must be assumed during the design and specification phases of a project and may not be suitable for all operations. Some passive systems have the ability to be manually adjusted, but this may be difficult while underway, at night, or during extreme motion and requires operator competency training. Further, an incorrectly adjusted seat suspension can increase the potential for injury.

Semi-active suspensions, in response to wave conditions, adjust suspension parameters to control seat movements with an onboard computer. Semi-active systems automatically adjust damping parameters to maximize shock mitigation capability for any occupant weight and modify the seat response to each wave impact severity. As a result, dramatic increases in shock attenuation can be realized.

“The introduction of commercially available computer-controlled semi-active shock mitigation seats is an interesting development. It demonstrates that shock mitigation seats are evolving into more complex and hopefully more capable, advanced technologies. This holds the promise of enabling better protection for personnel operating in extreme conditions.”

Builders and others in the maritime procurement chain should be aware of both existing and forthcoming requirements mandating RS & WBV mitigation. Government agencies, particularly in the European Community have recognized the importance of addressing the long term effects of WBV & RS by enacting legislation (2002/44/EC). This legislation sets limits and requires all employers to effectively mitigate personal exposure in the workplace. Because of the nature of operating in the marine environment, crews can exceed these limits in short periods in what would be considered “calm” seas. The EU legislation allows for some relief to maritime employers but is only applicable to certain groups under specific conditions with increased health monitoring. Other world governments see the issue as well and are learning from the challenges and successes of the EU experience. Beyond government, specialist and other military organizations at the highest levels are now recognizing the relevance and currency of reducing exposure to repeated shock and whole body vibration.

Mark D. Lougheed (SNAME) is the Engineering Projects Leader – Technology Development for CDG Coast Dynamics Group Ltd. Mark’s career spans 25 years as a high performance military and commercial craft designer.

E: [email protected]

References:

[1] John Haynes AFNI - Operations Director - Shock Mitigation Directory, FRC International

[2] J.L. Colwell and L. Gannon, Defense Research and Development Canada – Atlantic, Dartmouth NS, Canada

T. Gunston, VJT Technology Test Laboratory,

Southampton, UK

R.G. Langlois, Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Carleton University, Ottawa ON, Canada

M.R. Riley, The Columbia Group, Vir-ginia Beach, USA

T.W. Coats, Naval Special Warfare Center Carderock Division Detachment Norfolk, Combatant Craft Division, Norfok, Virginia, USA

[3] W. Ensign (et. Al) – A Survey of Self-Reported Injuries Among Special Boat Operators, Naval Health Research Center, Report 00-48

[4] Christopher Liam, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg Virginia, USA

[5] Petersen R & Bass C, Impact Injury and the High Speed Craft Acquisition Process, RINA Conference on Human Factors in Ship Design Safety and Operation, London, UK ,2005

[6] Schleicher Dean, Research Plan for the Investigation and Fatigue Criteria for Personnel Aboard High Performance Craft, 2nd Chesapeake Power Boat Symposium, 2010

[7] Kearns Sean, Analysis and Mitigation of Mechanical Shock Effects on High Speed Planing Boats, Boston University, 1994

(As published in the September 2013 edition of Maritime Reporter & Engineering News - www.marinelink.com)