U.S. Maritime Security: The Portunus Concept

The mission of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) is to strengthen United States’ security through development and application of world-class science and technology. LLNL seeks to enhance the nation’s defense; reduce the global threat from terrorism and weapons of mass destruction; and respond with vision, quality, integrity and technical excellence to scientific issues of national importance.

The Portunus concept embodies each of these objectives by thoughtfully and methodically developing technologies and strategies that address desired improvements in our security strategies. What may be unique about this concept however, is that we would accomplish this objective while enabling the U.S. to be the world leader in efficient goods movement.

Our current defense in depth strategy uses a variety of programs such as the Container Security Initiative, C-TPAT, and electronic manifest submittals for screening in advance of arrival. Several reviews by government and non-government agencies have highlighted some weaknesses in these programs. Given the current capabilities of our adversaries, these programs however may be sufficient to provide protection. That may not hold true for the future.

Learning from the Cold War, we understand that our adversaries can use our need for security as a weapon. It costs relatively little for a terrorist to execute an attack on the U.S. The protection against such an event consumes comparatively enormous amounts of resources. Some of those resources are directed overseas and necessitate a reliance on foreign governments for our protection.

If we can turn this dynamic around, so that our security process actually strengthens our economy, then we win this battle in the war against terrorism. Inspection of freight offshore but within the control of the United States is a tough goal. It is difficult for two reasons: (1) It is thought to be an economic poison pill, and (2) It may be technically unfeasible. Clearly, any offshore port strategy must make sense for business if we expect any credibility in its adaptation.

With this at the forefront of LLNL’s planning, the Portunus concept is designed to inspect up to 100 percent of transoceanic vessels, containerized, bulk freight and private craft before they get to U.S. ports by establishing a series of state-of-the-art offshore ports.In so doing, we can provide protection and improve port operations by decreasing freight offload times by 30 percent or more, improving intermodal connectivity, and allowing the most efficient movement of goods to consumers across the U.S.

Preliminary work shows this can be accomplished while providing benefits for the environment, domestic employment, infrastructure protection, and government finances.

Portunus is a technology development project that evaluates and optimizes floating and fixed structures for offshore use. These structures are modular in design, start out small and can be utilized for other ocean industries while in the development cycle. As the security risk grows, so do the capabilities of the offshore platforms. From a mechanism to offload, inspect and reload freight offshore from a single ship, to a large trans-shipment port servicing many ships.

In its most advanced stage, the Portunus trans-shipment port has distinct sections. The first section serves international shipping. This is where freight is offloaded and exports are loaded onto large ocean-going carriers. Containerized freight is then moved by automated guided vehicle to the next section. Bunkering, power, maintenance and repair support is provided along with hospitality services.

The second section is the security and inspections section. A security screening for human trafficking, radiological/nuclear material, chemical/biologicalweapons and contraband, such as explosives and drugs, is performed here. Advanced imaging and detection technologies, currently in development, are paired with high-speed computational capabilities and data warehouses to compare against electronic manifests and historical records. This data can be used as an operational aid to screeners minimizing false positives and negatives.

Throughout the process of offloading and inspection, a logistics program assigns the container to a location in a stack on the domestic section of the port. Freight in this section is staged for trans-shipment onto smaller ships that optimize transit to a domestic port for the most efficient delivery possible.

This trans-shipment port has advantages beyond security. Given the importance of protecting our coastal population centers from a WMD attack, providing for more secure borders from human trafficking and smuggling, and maintaining the resiliency of our critical infrastructure is important, we also want to see where the economic benefits come from.

These offshore ports can couple the most efficient way to move goods internationally (ultra-large containerships), and the most efficient way to move goods domestically (short-sea shipping), with an efficient port that can offload eight 18,000 TEU ships simultaneously in 36 hours. The process can move the sorting of freight that now occurs after cargo enters domestic ports, to offshore. This allows freight to be “packaged” for delivery to domestic ports nearer to final destinations or to areas with efficient intermodal connectivity through a hub and spoke distribution system.

Faster turn-around time for the larger ships allows more trips per year and more time at sea, increasing profits for ship owners. The faster processing of freight, hub and spoke distribution, and concurrent customs inspection allows for the faster delivery of freight. An economy of scale is achieved when new technologies are developed. Implementation and investment occurs at relatively few offshore ports instead of significant investments duplicated at all major ports in the U.S.

Technology development of offshore platforms provides economic growth and capabilities in vital industries, such as shipbuilding, alternative energy, desalinization, aquaculture, and LNG exports. Offshore platforms also facilitate access to remote areas like the Bering and Beaufort Seas, which opens up possibilities for artic shipping routes and port expansion.

Domestic job creation is achieved by strengthening our merchant marine and shipbuilding industries. Along with this are collateral benefits of support industries and services along with additional tax revenues from domestic activity. Overseas spending is reduced because we can redirect existing spending to domestic needs.

Using a study conducted by the United Kingdom, by inspecting 100% of inbound freight, additional government revenues are estimated of about $2 billion per year with an accurate assessment of imported goods.

Currently, larger ships make one or two stops at major ports, and freight is moved to regional distribution centers by truck or rail, bypassing smaller ports. In the Portunus scenario, smaller ports and ports with good intermodal connectivity provide an advantage for goods movement to their regions and remain vital because smaller craft can move directly from the offshore platform to that domestic port.

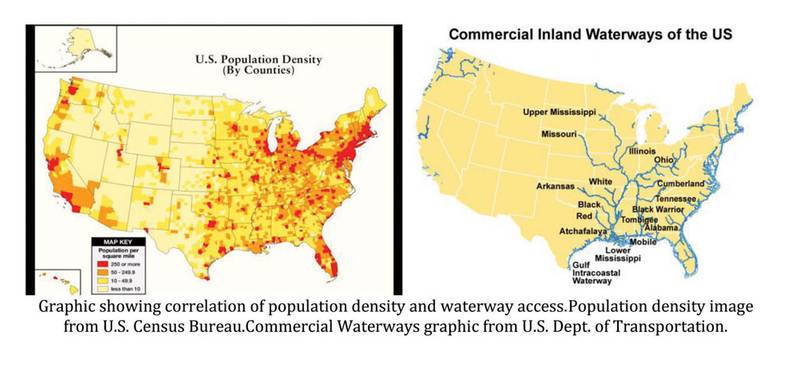

In addition to security and economic benefits, environmental benefits are achieved in many areas. As an example, by keeping international ships offshore we can minimize environmental impacts such as invasive species. The need to maintain deep harbors through increased dredging is minimized because the larger ships won’t move into most ports. By using a more efficient mechanism of transport, air pollution and fossil fuel use are minimized. This process replaces much of the long haul truck traffic currently congesting freeways with barges and smaller ships able to navigate coastal and inland commercial waterways. This also reduces traffic and freeway maintenance needs.

The natural skepticism that this game-changing technology invokes is understandable. That is why the Lab has worked with ports, economists, universities, merchant marine, shipping companies, engineering firms specializing in offshore structures, terminal operators, and technology companies, among others to provide a strategy that makes sense. The first objective of the concept is to evaluate associated technologies.

Concentrating on computer-aided design and simulation we will evaluate technologies that can be applied for the construction of offshore platforms of various sizes to meet specific mission needs at relatively low cost.

Interim steps in prototype development will help generate private investment into new industries for the U.S. economy. Ultimately, we may be able to produce offshore structures capable of processing and screening commercial maritime and private transoceanic craft.

In addition to a technical feasibility study, a detailed economic analysis will need to be performed not only concentrating on the costs of capitalization and operations, but on regional and business sector impacts. These studies will necessarily integrate with the technology study to provide operating and design parameters.

The last front in this feasibility assessment is the legal and regulatory framework that will be applied. All three fronts will need to be interlinked and coordinated. The development of these technologies on the scale required will take some time. Too fast an implementation will cause unnecessary and unwanted turbulence in a critically important economic cornerstone of the U.S. economy. Too slow an implementation runs the risk that we may not have a sufficient strategy in place to protect ourselves, without undue economic hardship, when our adversaries have a known capability of delivering a WMD to U.S. soil.

(As published in the September 2014 edition of Maritime Reporter & Engineering News - http://magazines.marinelink.com/Magazines/MaritimeReporter)