Maritime Security: Neo-colonialism in the Gulf of Guinea

Is neo-colonialism in the Gulf of Guinea the answer to West Africa’s maritime crime crisis?

In October 2020, China’s transport ministry established an ad hoc workgroup to lay down precautionary measures for ships and seafarers passing through high piracy risk West African waters.

The move came as China told its vessels to up vigilance and implement a series of precautionary measures to ensure the security of ocea-going vessels and seafarers amid rising attacks and a surge in kidnaps in the Gulf of Guinea.

Plans outlined by Wu Chungeng, a spokesperson of the Ministry of Transport, included strengthening the ability to collect safety information in areas with high risks, and to broadcast piracy activities and alerts via mutual channels. Similar calls for heightened vigilance were echoed by Chinese embassies in Togo and across West Africa.

Recent West Africa maritime security incidents involving Chinese vessels

February 9, 2018 - kidnapping - 10 nautical miles offshore, south of Bakassi Peninsula

At 0300 hours local time, when operating at about 10 nautical miles south Bakassi peninsula, four fishing trawlers were attacked by unknown sea pirates. It was reported that six crew members were kidnapped, including three Cameroon and three Chinese.

March 22, 2018 - kidnapping - southwest of Lagos

Some 13 nautical miles south of the Nigerian coast south west of Lagos, pirates in a speedboat attacked and seized two fishing boats and forced them to sail into Benin waters. The fishing boats were later released, two crew members were kidnapped.

March 23, 2018 - kidnapping - 10 nautical miles from shore, south of Bakassi Peninsula

After the fishing trawlers Luwn-Yu 1 had been attacked in same area on February 9, three crew members were kidnapped.

February 23, 2019 - kidnapping - offshore Idenao

Tree Chinese fishing vessels were attacked and boarded when operating offshore Idenao, Cameroon waters. Reporting indicates that eight fishermen, believed to have been Chinese, were abducted.

December 22, 2019 - kidnapping - Owendo anchorage - Gabon

After about midnight, a landing craft was boarded by pirates from a canoe similar in description to the suspicious approaches 90 minutes earlier. While on board, the vessel master was killed. Two fishing vessels (that were under detention by local authorities) were boarded by pirates from a canoe. The Chinese captains and chief mates on each vessel were kidnapped (four in total).

July 3, 2020 - kidnapping - around 150 nautical miles south of Cotonou, Benin

Armed pirates attacked and boarded a general cargo ship that was drifting and awaiting operational instructions. They kidnapped five crew members, stole the ship’s properties, including cash and crew's personal belongings, before escaping in a small boat.

November 13, 2020 - fired upon - 78 nautical miles northwest of Neves

Pirates armed with rifles in a small boat approached the ship underway. They boarded the ship, opened fire and injured one crew member. Before escaping, the pirates stole ship and crew properties and kidnapped 14 crew members. The ship's owner notified the IMB Piracy Reporting Center who then liaised with relevant regional and international authorities in the region and requested for assistance. Italian, Spanish and Portuguese naval vessels arrived at the location and aided the ship. The injured crew was transported on an Italian aircraft to the hospital in Sao Tome and Principe. The ship and remaining crew were escorted to a safe port.

| West Africa maritime statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WAF | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| Approach | 21 | 19 | 10 | 25 |

| Kidnapping | 11 | 15 | 28 | 27 |

| Attack | 5 | 5 | 5 | 8 |

| Fired Upon | 10 | 21 | 19 | 11 |

| Attempted | 8 | 9 | 3 | 8 |

| Boarded | 15 | 19 | 13 | 21 |

| Robbery | 16 | 40 | 31 | 31 |

| Hijack | 1 | 2 | 8 | 1 |

| Kidnapped Crew | 111 | 156 | 177 | 138 |

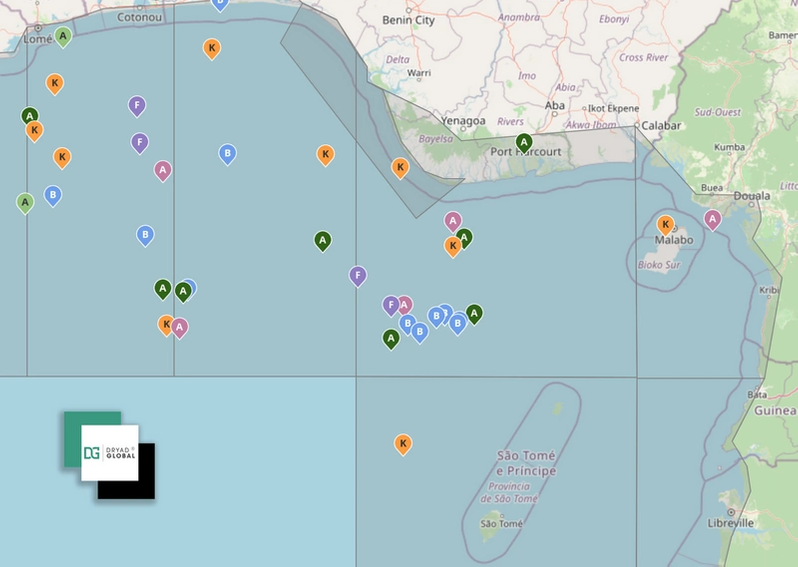

These moves come as nearly half of the 111 incidents at sea reported in the area in 2019 took place less than 12 miles from the coast. However, 2020 saw an uptick in longer range piracy attacks across a wider area and against different types of vessels likely backed by transnational organized crime groups using a kidnap and ransom strategy to leverage cash. In the first nine months of 2020, kidnappings in the Gulf of Guinea soared 40% in comparison to the same period in 2019. It is this “professionalization” of piracy in the region that is finally commanding the attention of international players.

The impetus for international players with interests in the region to start providing tangible and long term support to the Gulf of Guinea nations is on. The need for training, and partnership to compliment the proper deployment and operation of naval assets in the region is essential to better protect commercial shipping in these waters. At a cross-governmental level sustained initiatives to tackle illegal fishing and improve port security are also fundamental to successfully tackling the wider regional maritime security issues.

What international efforts are being taken to empower and develop West Africa’s maritime security and naval capacity?

The shift in West African maritime criminal modus operandi and growing concern about maritime security in the Gulf of Guinea has prompted international efforts to boost regional naval capacity, including recent procurements of maritime-patrolling equipment by Angola, Cameroon, Republic of Congo, Nigeria and Senegal, among others.

However, navies in the region are reluctant to better fund their navies, given other priorities, which include addressing their vulnerability to land-based threats. This is alarming given that as of 2019, almost 50% of all piracy and incidents of robbery at sea reported in the Gulf of Guinea took place in the maritime approaches of Cameroon and Nigeria.

In the absence of sustained investment in maritime capacity building, the Nigerian Navy has successfully turned to the private sector, establishing a robust operating model to increase assets and capability. This approach has ensured stakeholders and end users have access to appropriate risk mitigation tools, though this relies heavily on the availability of suitable security patrol vessels.

“There is an alarming oversupply of grossly unsuitable security escort vessels. Successful implementation of the Nigerian operating model relies on the enforcement of Nigerian Navy criteria for security escort vessels, delivered compliantly within the regulatory framework clearly laid out by the Nigerian authorities,” said James Hilton, Protection Vessels International, Managing Director.

He added that the demand for fast, fit-for-purpose patrol vessels in the Gulf of Guinea has doubled in the last two years.

“Our in-country operations teams have been delivering operationally effective fully compliant solutions in West Africa for the last six years. Very early on, we identified an immediate need for modern, well-maintained vessels fitted with the latest monitoring equipment and operated by trained personnel. Without these key components, affecting tangible change in the region to curb the rise in maritime crime incidents would be near- impossible,” Hilton said.

(Video: Protection Vessels international)

The young populations of these countries also hold a degree of resentment toward the international companies that are benefiting from “their” offshore oil but seeing no tangible benefits to their own lives or communities.

And indeed, to a point, they are quite right; but the reticence of regional navies to act means that a further channel for ambitious global players is laid wide open. Beijing is never slow off the mark when an opportunity presents itself to extend its influence and regional involvement in a resource rich part of the world. Cue the notable upgrade of Ghana’s navy with the donation of four small patrol boats from China on the discovery of offshore oil deposits in their territorial waters. Between 2012 and 2019, in what constitutes a noticeable breakthrough for Chinese shipyards in sub-Saharan Africa, Chinese companies exported 13 vessels to Cameroon, Republic of Congo and Nigeria, including two 1,800-tonne Centenary-class offshore-patrol ships. Beijing’s efforts to gain influence in the Gulf of Guinea also takes other forms, from the construction of maritime infrastructure to the development of military cooperation within the Framework on China–Africa Cooperation. And it’s not just China, Nigeria procured ten patrol boats and patrol craft from French companies from 2011 to 2017 with Senegal too, procuring six French vessels between 2012 and 2019.

Is it a coincidence that the renewed international interest in West Africa’s precarious maritime security situation comes hot on the heels of the discovery of offshore oil deposits? Is the increase of sea traffic as a result of these discoveries providing more opportunities for maritime criminals?

Whatever is driving the renewed calls for action, what’s clear is that with China as one of the largest exporters of goods to the African countries in the region, where it also imports raw materials such as crude oil, its interests are very much at stake.

"It does not do to leave a live dragon out of your calculations..." - J. R. R. Tolkien, The Hobbit.

What is China’s long-term investment in West Africa?

In 2013, China launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to strengthen its state-owned enterprises, create new export markets and establish its geopolitical power. China began investing in African and Asian transportation, energy and infrastructure, most recently focusing on oil-rich states in the Gulf of Guinea.

These Chinese investments have come in the form of commodity-backed loans, where China receives control, or payments, of a commodity if the beneficiary defaults and lofty infrastructure projects that often stipulate a percentage of Chinese state control. The U.S. believes its energy, humanitarian and security interests in the region could be jeopardized if China continues on its trajectory to become a neo-colonial puppet master in the Gulf of Guinea.

Why is the Gulf of Guinea strategically important to China?

The Gulf of Guinea consists of Ghana, Togo, Benin, Nigeria, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Sao Tome, Principe, Angola and Congo.

- 60% of its population is under the age of 25.

- 2.7% and 4.5% of the world’s reserves in gas and oil respectively originates from the region.

File photo: Bonga FPSO off the coast of Nigeria (© Giles Barnard - Photographic Services, Shell International Limited)

File photo: Bonga FPSO off the coast of Nigeria (© Giles Barnard - Photographic Services, Shell International Limited)

What are the regional threats plaguing the region?

- Vibrant potential markets

- Persistent jihadist threats

- Petro-piracy and impact on local population’s ability to benefit from Africa’s growing maritime economy

- Weak governance and corruption

- Illegal fishing

- Growing international political focus on the environmental impact of maritime activities.

How far does China’s influence in the region extend?

In a modern take on the silk road, China is playing a long game, cementing its influence in West Africa. This can be seen in various regional projects supported by China:

- Angola is by far the largest recipient in Africa of Chinese loans, with US$21.2 billion in cumulative loans between 2000 and 2014. China imports 49% of Angola’s oil, partly in repayment for those loans

- Ghanaian electricity infrastructure

- Benin railroad contract

- Ghana, Niger, Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea credited with over US$2.5 billion each backed with each states’ oil.

A component essential to the BRI is that China implements no conditions about human rights, governance or military operations in its contracts, which allows it to nurture authoritarian regimes, like Cameroon, and makes no commitments to counterterrorism in the region.

China’s reach has also extended into softer influence outlets such as institutions, state-sponsored learning centers and an African news network, to reshape African countries’ media landscape.

China’s telecom investments through Huawei Technologies and ZTE, whose largest shareholder is a Chinese state-owned firm, have established more than 40 third-generation telecom networks in more than 30 African countries. Chinese firms also make a huge number of the cell phones sold on the continent. Transsion Holdings, which doesn’t operate in the United States or Europe, accounts for 30% of African phone sales (under its brand Tecno Mobile), ahead of second-place Samsung at 22%.

With its unmatched access to African audiences, China is also investing in the content and infrastructure of African television. In 2012, China established CCTV Africa, which was then renamed China Global Television Network (CGTN) Africa in 2016 and incorporated into the Voice of China media group in 2018—an English-language news channel run by the Chinese state broadcaster. To compliment this investment China continues to shape the careers of African journalists through high-level media cooperation initiatives and new China-Africa press centers. Every year around 1,000 African journalists participate in training programs in China with the aim of building better understanding and cultural ties with the country (*Source: Foreign Policy).

What do Chinese loans finance in Africa?

Transportation constitutes the largest sector financed by Chinese loans at US$24.2 billion. Energy (mainly power) is the second largest sector at US$17.6 billion, followed by mining/oil at US$9 billion, and communication projects at US$6.5 billion. The bulk of the rest are large lines of credit that fund projects in several sectors, or loans that have been signed, but the purpose is either undecided or unpublished. More than 83% of the mining sector loans went to Angola’s state-owned oil company, Sonangol, with two gold mines in Côte d’Ivoire and Eritrea, a uranium mine in Niger, a copper mine investment in DRC, and a geo-chemical mapping project in Morocco making up the rest (*Source: SAIS China-Africa Research Initiative).

© Manola72 / Adobe Stock

© Manola72 / Adobe Stock

How will China’s influence in the region play out in 2021?

“Undeterred by a shrinking global economy and the COVID-19 pandemic, China adopted a more assertive approach to foreign policy in 2020,” said Dryad Global analyst Sarah Knight.

“This 'wolf warrior' approach signals that China will be increasingly determined in its foreign policy pursuits, including further strengthening the BRI in key regions such as West Africa. As competition between the U.S. and China increases and the global economy recovers, efforts to ensure energy security and international influence in the region will be important to China in 2021. However, the U.S. and European states are aware of these ambitions and are working to counterbalance China’s increased assertiveness,” she added.

Within West Africa, and unable to compete with the significance of China’s onshore grown in strategic influence, European states have been forced to take the lead in providing capacity building and maritime domain awareness training to west African states. However, these have thus far followed post-colonial interests with France, Portugal, Spain and Italy having the greatest commitment to the region. With China already focusing its sights on its maritime String of Pearls as the maritime component to the BRI it won’t be long before it starts to dominate the maritime space in the same manner as it has on shore.

Despite the continuing commitment of West and Central African leaders to the 2013 Yaoundé Process and improvements to information-sharing endeavors Centre régional de sécurité maritime de l’Afrique de l’Ouest (CRESMAO) in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, and Centre régional de sécurité maritime de l’Afrique centrale (CRESMAC) in Pointe-Noire, Republic of Congo there remains significant opportunity for improved intra-regional cooperation and international engagement.

We are seeing moves in the right direction. Exercises such as Obangame Express 2019, under the auspices of U.S. Africa Command, have focused on developing relevant skills, such as vessel-boarding techniques, search-and-rescue operations, medical-casualty responses, radio communications and information-management techniques. The regional African NEMO exercise series and the more ambitious Grand African NEMO exercises also focus on skills development.

While we’re likely to see a step change in U.S. and European nations support to the region, China will also muscle in on the action, albeit with a more subtle approach.

The region’s resource potential and prospects for its greater integration into the international economic system are too great a lure to ignore, and akin to the Indian Ocean, the stakes are too high to blindside. In previous years, local capacity-building, has been significantly constrained by a lack of funding. However, we’re likely to see these financial obstacles alleviate in 2021 as professional companies like Protection Vessels International are contracted and tasked with providing long-term partnering to strengthen and develop local navies’ capability and readiness to tackle an able and well financed burgeoning maritime criminal network.

Prioritizing investment in training and the mentoring of indigenous commercial and naval operations will also grow as the need for properly trained crews and able officers grows. In terms of equipment, as maritime criminals improve the vessels and intelligence gathering tools they use, the need to overhaul existing fleets and replace them with functioning patrol boats and a supply chain of spare parts and trained technicians will also emerge. Again, this presents a key opportunity for ambitious regional players to expand their influence across African naval infrastructure by developing repair and maintenance facilities. Will China, the U.S. or France lead the charge? At this stage it’s too early to tell. But what we do know is that all is up for grabs as these key players take a neo-colonial approach to the Gulf of Guinea region.

There isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution for the region’s persistent maritime challenges. The weight of responsibility is on us, the maritime industry, to ensure that the essential improvements to maritime security in the region are sustained, fair, ethical and place Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) at their core. Solutions must be implemented that complement domestic law enforcement capabilities and economic development initiatives. Better integrating local populations into the maritime economy is essential; jobs must be secured for local people and revenue fed back into bonafide community initiatives. The key to security progress in the region is in securing the ethical wholehearted support of both the international community and the buy-in of local states and regional indigenous navies.