INSIGHTS: Michael G. Johnson

Sea Machines Robotics CEO & President.

Michael Gordon Johnson is a marine engineer, an accomplished entrepreneur and sector leader with a primary goal of building progressive and sustainable innovation for modern society. He is the founder of Sea Machines, a Boston-based tech company that is a leading provider of autonomous control and intelligent perception systems for marine vessels. Johnson earned a marine engineering degree from Texas A&M University before starting a career focused on complex projects in offshore oil and gas, marine transportation and salvage. Prior to starting Sea Machines, he was a vice president at Crowley Maritime Corp. and their affiliate company, TITAN Salvage.

Johnson and his fledgling Sea Machines firm today find themselves at the leading edge of that which will soon (perhaps) become the biggest disruptive event on the commercial waterfront in more than a century. Autonomous marine vessels promise an unprecedented era of safety, increased efficiencies, and the introduction of myriad skill sets to a previously conservative industry with a reputation of being anything but an early adopter. For many years, progress on the waterfront was measured in metrics such as ever larger deadweight tonnage and the increase in vessel length, breadth and draft that drove that change. What comes next will be entirely different. Michael Johnson and Sea Machines will be there when it happens. This month, listen in as Johnson leads the evolving discussion that will change the marine industry forever.

Your firm was found in 2015. Give us a sense of just how far you have come, since then.

In January 2015, Sea Machines was an idea and one person with a shared office in Cambridge and working with a company called Jaybridge Robotics on our first prototype autonomy system. We bought a 25’ steel twin-screw azimuth German tug and opened a shop in Boston Harbor Shipyard. We started with developing wireless remote control, fumbled with various types of low-level automation systems until we settled on Siemens PLCs. After trying various types of autonomous control techniques we settled on the current SM300 architecture in May of 2017 (two years after founding) and began the ‘productization’ process of the systems. In late 2016, we were accepted into a start-up accelerator called MassChallenge where we emerged one of the winners and received our first bit of outside funding. We then recognized that it was time to pursue venture capital. We closed our first round of $1.5M in funding early 2017 and a second round of $10M in late 2018. We now have industrial marine-grade autonomy and remote control products on the market and have grown to a team of 35 with offices in Boston, MA and Hamburg, Germany. I now hear many refer to Sea Machines as a leader in this space.

Give the readers a quick overview of your product offerings.

We sell both the SM200 and SM300. The SM200 is a wireless control system; it puts the helm and payload control of the vessel onto a personal belt-pack controller which is a joystick control station that belts comfortably around a person’s waist. The SM200 allows a vessel operator the freedom to control a vessel and it’s auxiliaries from outside the pilot house and frankly anywhere within 1 to 2km of the vessel. Operators are purchasing the SM200 to alleviate pilot-house blind spots, enable the vessel to be controlled from the load (barge) or from a better vantage point of where the vessel is to make contact or being made-up such as ATB pin connections. The SM200 has passed all testing by Bureau Veritas and by time of this article should have received ABS and U.S. Coast Guard acceptance for installation on specific classed U.S.-flag vessels. The SM300 is our flagship autonomous control system which enables man-in-the loop autonomous control of workboats. The system is being deployed on commercial and security related operations where autonomy empowers the vessels to operate safer, longer, with greater precision, predictability, and productivity. This can be bathymetric survey or data collection, dredging, oil spill response, fire fighting, long duration surveillance or escort operations. The SM300 can work alongside an on board crew or enable the vessel to operate unmanned within a monitored domain.

Have you sold any systems into the marine markets, as yet? If so, where and for who? Is that system on the water in service yet?

Yes, we have sold Sea Machines systems in multiple markets both domestically and internationally. Due to the nature of commercial vessels and their operational vs. refit schedules, we are seeing 4 to 8 months between order and actual deployment the units. By the end of this year, there should be more than 25 units purchased and 10 units deployed and in use globally. We will announce those that we can; to date we’ve told the world about an SM300 purchased by Hike Metal in Canada for the SAR market as well as an SM300 purchased by MARAD and installed on an MSRC Kvichak oil skimmer boat.

The autonomous market for the maritime industry targets ‘dull, dirty and dangerous tasks.’ Tell us what your market focus will be for the near term. Blue water or brown? Commercial or military? Mission descriptions?

Indeed, advanced robotics in almost all markets is quick to find value in the dirty, dull, and dangerous tasks. In our market, we qualify long duration tasks requiring continuous attention but little dynamic change as DULL and in the marine domain many operations fall into that category, but narrowing it further our current tech is not yet validated for complex traffic situations so we are selling to coastal and open water operators that are focused on tasks such as survey, oil spill response, aquaculture, security or inland operations that are working in a controlled or semi-controlled domain such as dredging. We are selling to both commercial and government markets.

Where do you see the greatest opportunity for autonomous waterborne operations? What’s the next big thing? Why?

Autonomous Navigation & Advanced Situational Awareness; these are the next big things and why we are focused on them. I say “next” even though we offer them now because today it’s the innovators and very early adopters that are trying the technology but within the next few years there will be a tipping point of demand and these technologies will be on the road to becoming a standard part of all vessels. Why?, because of the leap in productivity, performance, and safety offered by these systems, moving marine operations up the ladder of modernity to reduce our annual accident rate, both in commercial and recreational, improve on-time performance, and reduce operational expenses. Ultimately, this will enable new types of operations and business on water that are impractical with established technologies.

It has been said that the dirty little secret behind autonomous marine operations is that autonomous doesn’t mean unmanned. Would you agree with that assessment? Why, or why not?

We agree, autonomous does not mean unmanned. Autonomous is an aspect of an advanced vessel control system. Manned, reduced manning, or unmanned is an operational decision. We build the technology that enables safe and productive machine-driven navigation and control of the vessel, but a human operator remains in command, meaning that they plan the missions and monitor as necessary. That operator can be on board or remote from the vessel.

What is the greatest distance today that one of your autonomous systems can be controlled by another vessel/person? Must that control be ‘line-of-sight?’

For demonstration purposes we’ve conducted a number of transcontinental and transoceanic operations (meaning that the human operator is one side of the continent or ocean with the autonomous vessel on the other side – California/Boston, or Denmark/Boston); however, in most current actual applications the operator will be located within a few miles. Most of the systems that we sell are integrated with IP radio for line-of-sight as well as 4G communications so as long as the vessel is within 4G range the operator can be anywhere with connectivity.

Sea Machines Robotics recently announced a new partnership with Hike Metal, a manufacturer of workboats based in Ontario, Canada. You’ll integrate Sea Machines’ SM300 autonomous vessel control system aboard commercial vessels tasked with search-and-rescue (SAR) missions. Tell us about how this will help SAR ops.

SAR vessels are limited in capacity and by using an autonomy system to effectively pilot a vessel from point-to-point or on a grid/sweep pattern over an area, you can pull a crew member away from the task of manual driving and put them to work scanning the waters or helping respond to persons in need. Let the technology do the repetitive work and utilize a human for more complicated and unique tasks.

Sea Machines started out with close ties to Denmark-based boatbuilder Tuco Marine. Are you still partnering with them on projects?

Indeed, we love Jonas and his team at Tuco. He’s actively selling vessels into the offshore wind and aquaculture markets, and we are in discussions with multiple operators there. So, we should see results of our collaboration with Tuco soon.

You’ve said that “when it comes to command and control systems, data communication, collection and interpretation – advances in these areas will push forward a new era of marine and maritime operations.” Flesh that out a little for us – what does it really mean?

In today’s marine world, command and control remains so very 20th century. Big advances last century were auto-pilot, RADAR, AIS, automation/unmanned engine rooms, ECDIS, GMDSS. But even in today’s newest ships, our command and control remains very human-manual, meaning that all piloting decisions come from the minds of those controlling the bridge. As an industry we tout modern networked logistics platforms or the advances we’ve made in weather routing, even some of the latest situational awareness systems from the big European OEMs, but these cutting edge technologies in almost all situations output their intelligence via an email or PDF file to an officer in command that then needs to make navigational decisions based on the information, much as humanity has been doing since the first ships were put to sea. What we are building is what the operators are aiming toward, moving the human up the ladder and away from direct and continuous control decisions, and empowering the vessel to control itself with exacting precision and productivity. For example, collision avoidance that detects and tracks all items within the operating domain even when navigating through busy fishing areas, the logistics platform which sees a cargo delay in an upcoming port of call due to high winds then communicates to the vessel that is currently crossing the Atlantic to slow by 1 knot, or having a vessel make navigational decisions based on weather forecasts. This technology will open a new era of less accidents, increased predictability and productivity that is beyond a level that can be achieved in a human-direct controlled world.

When we last visited your Boston-based operations, you were testing on the waters of Boston Harbor – where do you stand now in terms of products ready for the market?

Sea Machines products are on the market, but we continue to advance the technology and with our current test fleet of 3 vessels and 3 full time captains, you can see us in Boston harbor and offshore daily.

You started out with a test hull – a German-built Bodan-Werft river/coastal tug with twin Schottel Z-drives. You chose the boat because many workboat operators now deploy Z-drives and because you wanted to prove to yourselves and others that you could readily convert a completely analog/mechanical control boat to electronic fly-by-wire remote command. What were the biggest challenges with the refit?

The biggest challenge in that conversion, which was our first, was our attempt to build our own electrical-mechanical steering system for the mechanical-manual Z-drives. It was okay for a while and it convinced us that we do not want to be a company that builds new hardware. We build new software that is deployed on systems that we’ve assembled using proven off-the-shelf hardware that has been built and tested by other leading companies. That German Bodan-Werft tug now is hard at work making money for a company in Gloucester.

Significantly, you’ve raised a fair amount of venture capital – people obviously believe in what you are doing. These firms include Launch Capital, along with Accomplice VC, LDV Capital, the Geekdom Fund, Techstars and others. What has this funding done for you now that you couldn’t accomplish before?

You can add Toyota, Brunswick, Eniac VC, and NextGen to that list. This funding has enabled almost everything we’ve accomplished since 2017, such as building a leading advanced product development team, acquiring the assets for testing and validation, and expanding our presence in Europe.

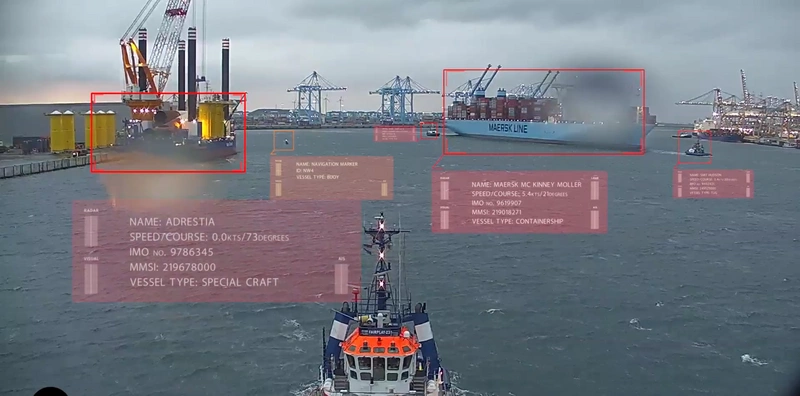

In the first quarter of 2019, Sea Machines was to initiate testing of its perception and situational awareness technology aboard one of A.P. Moller-Maersk's new-build ice-class container ships. How has that testing progressed?

Yes, we officially powered up the prototype system on the Vistula Maersk in March of this year. Testing and iteration of the technology is progressing nicely.

The Maersk collaboration is significant in that many stakeholders feel that, while brown water autonomy is certainly viable (and happening in increasingly large numbers of hulls), blue water operations are quite a bit further out. What’s your take on all of that?

From a technical complexity standpoint of autonomous tech, blue water and coastal gets to market before brown water (rivers and canals). Brown water is a more complex operating environment with respect to obstructions and traffic.

You’ve got two primary offerings at this time – the SM200 and the SM 300 – and another, the SM400. What’s unique about each and which sector is each targeted for?

SM200: Industrial-grade wireless remote control for tugs, daughter craft, or tenders.

SM300: Industrial-grade autonomous control for surveying, oil spill response, dredging, surveillance, aquaculture.

SM400: Advanced situational awareness for merchant ships.

What is the single largest impediment to autonomous operations on the water today? Is it local and/or flag state regulations, resistance from existing stakeholders, cost, or a combination of the three?

The single largest impediment is finding those dynamic progressive operators that are willing to look beyond the proven conventional and seriously try new technology in an attempt to prove the value in their operations. This impediment (or challenge) is not unique to our space. How many trucking or taxi companies do you see with autonomous operations? Cargo jet operators? Long distance trains? The fact is that our domain and type of operations is suited for autonomy and remote operations and so it makes sense that we are deploying the tech in certain marine sectors ahead of those other industries. But still, big changes require effort, commitment, and time.

Autonomous and/or robotic operations – whether in port or on board vessels – are being met with fierce resistance by at least one sector – maritime/longshore labor. But, autonomy and robotics arguably don’t eliminate jobs; they act as a force multiplier while often increasing headcount. Would you agree?

Yes, on the macro level, I agree. Our country has been investing in automation for about 75 years yet today we have an unemployment rate of 3.7%. Almost everyone that wants to work in our country is working. I understand the concerns of longshoremen but they like everyone else work in an ever changing industry and have lived through change. Progressive change is good; it drives our ever increasing standard of living and standards of the workplace. I bet most longshoremen would choose to work in their highly automated gantry crane of today over the cranes of 30 years ago, or stick booms, pallets, and cargo nets of 50 years ago.

You’ve said that there are definite defense applications for autonomous marine systems, but that at the same time, you remain focused first on the commercial market. Is that still true?

We view the commercial space as a healthier free competitive market. It’s where we feel the most comfortable and the place for truly focused high-tech start ups. There are folks in the defense market that see the value in commercially-built technology and we are happy to serve them.

Do you hold any patents in this space? If so, tell us about those technologies / devices.

Yes we recently had one issued for the utility of autonomous vessel towing. We have many applications that are in process.

What’s been you biggest success so far for your relatively young firm? And, the biggest challenge? Are they one in the same?

Our biggest win and challenge is bringing the products to market in a standardized format. Most other autonomy providers build customized solutions for vessels whereas we offer systems that can be installed across your fleet of different vessel types.