Inside the Red-Hot Offshore Wind Energy Market

As the traditional offshore oil and gas markets continue to struggle, the renewable offshore wind market is hot and getting hotter.

As the cumulative maritime, offshore, port and logistics marketplace gears up for offshore wind energy on a huge scale, World Energy Reports (WER), in its report “2021 The Year When Offshore Wind Takes Off in the United States,” shows the anticipated growth trajectory. Service Operations Vessels (SOVs), which can commission and/or maintain turbines, are central to the plan, and Philip Lewis, Director of Research, WER’s, explains that SOV’s are deployed for several functions:

Turbine commissioning work during the construction phase for the turbine OEM, with campaigns planned in terms of months of activity and vessels deployed for relatively short periods.

Turbine maintenance for the O&M phase – this can be the turbine OEM as part of the warranty period (typically 2-3 years) or by the turbine OEM under a service agreement. Alternatively, it can be the wind farm operator.

General wind farm operations and maintenance by the wind farm operator for their planned routine inspection, repair, and maintenance activities. For most large windfarms, these can be 20-30 year deals.

Major offshore repair and maintenance for unplanned events, calling for the spot charter of specific vessels.

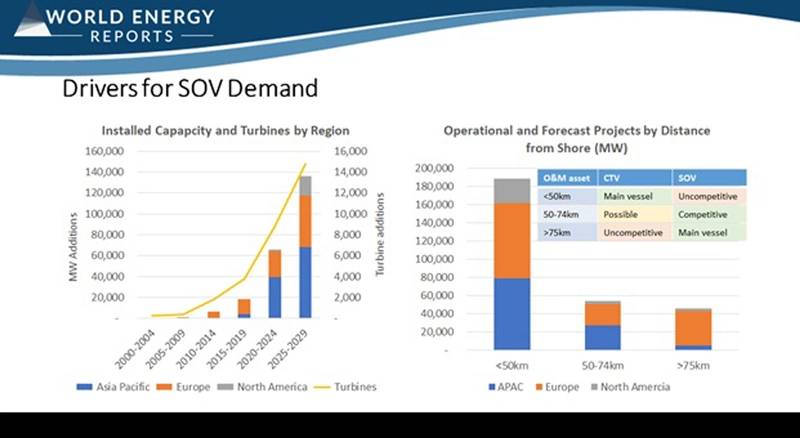

“Around 65% of the operational capacity and forecast for this decade will be within 50km from shore; for O&M, this generally drives Crew Transfer Vessel or CTV demand,” said Lewis. “For offshore O&M support, SOVs are generally competitive over 50km. This is because of the time taken to transit between shore and the wind farm, weather related availability and passenger comfort and safety.”

Recent months have seen a raft of new design and construction announcements. In the U.S. market, energy behemoth Ørsted, in conjunction with regional utility Eversource, announced they were entering into a long-term charter on a Jones Act qualified SOV that would initially be operating out of a base to be built in Port Jefferson on Long Island, serving three projects in the Northeast: Revolution Wind, South Fork Wind and Sunrise Wind. “Chartering strategies for SOVs, or CTVs for windfarms closer to shore, are still emerging,” said Lewis. “As an example, turbine OEMs could possibly employ an SOV across multiple installations, during the commissioning and warranty phases.”

The description of the 260-ft. EPA Tier 4 compliant diesel electric vessel, to be built in yards owned by privately held Edison Chouest Offshore (ECO), highlights the key attributes for SOVs. ECO describes the newbuild as “… a special-purpose design with focus on passenger comfort and safety, enhanced maneuverability and ship motions, extended offshore endurance and reduced emissions.” The vessel, as described, will have accommodation for 60 passengers, with a below deck warehouse (served by an elevator). A daughter craft, served by a height compensating landing platform, will be used for ferrying workers and equipment to the individual turbines for maintenance and repairs.

The choice of ECO (with an OSV fleet active in the Gulf of Mexico, Alaska and in Brazil) as a builder underscores an important trend: the transfer of offshore oil and gas experience (and on occasion actual vessels) into the burgeoning wind arena. But with offshore wind driven by a pivot away from fossil fuels, the “green” aspects are critical in the new wave of service vessels to be built; every newbuild or design announcement checks that box. On the ECO newbuilds, the electric motors tied to the vessel’s cyclorotor propellers will employ a Variable Frequency Drive (VFD), in a design proprietary to ECO.

Drivers for future SOV demand. Courtesy World Energy Reports

Drivers for future SOV demand. Courtesy World Energy Reports

SOV designs for the U.S. market

Multiple SOV designs have been announced for the U.S. markets. Vard Marine, the ship design arm of Fincantieri, has received Approvals in Principle (AIP) for two SOVs that could be built in U.S. yards. The compact 4 07 design, with 2,700 kW of propulsion power (suitable to carry 60 technicians) was announced in late 2019, while the larger 4 19, with 3,000 kW of propulsion power and capable to carry 90 technicians, gained the AIP in August, 2020. The 4 19 layout (with a full size helideck, and a 27m gangway) contemplates that battery power could be added later on, with space on deck for a future retrofit.

Wärtsilä Marine has also presented a 76m Jones Act compliant SOV design, which it describes as a “ hybrid multi-purpose SOV,” adding that: “The designers also worked closely with classification societies including DNV and ABS, which both provided valuable input to the vessel design.” Its announcement stresses that its “data driven” design process and its proprietary tools for optimizing engine performance. Wärtsilä also stresses the importance of integrating the vessel’s dynamic positioning system (where it has extensive experience linking DP with propulsion) to components such as the walk to work gangway.

Vessel designers Technology Associates Inc. (TAI), based in New Orleans, have adapted its designs, well known in the Gulf of Mexico’s oil and gas business, to the wind sector. The designer has introduced its EnviroMax Diesel-Electric Hybrid Service Operation Vessel (SOV) specifications for installation and maintenance of offshore wind farms. The TAI EnviroMax series of vessels have been designed to maximize operational capabilities, minimize fuel consumption and carbon foot print. TAI’s EnviroMax SOV designs are being offered in the “S” (Small), “M” (Medium) and “L” (Large) Classes.

A Jones Act compliant SOV design. Image courtesy Wärtsilä

A Jones Act compliant SOV design. Image courtesy Wärtsilä

Coming to America

Northern Europe is where the offshore wind business began, but the U.S. growth projections are attracting these European veterans. The Danish company Esvagt, in mid-March, announced a link-up with Jones Act veteran Crowley to participate in the burgeoning U.S. markets (See story pg. 40) Windea, a joint venture of a group of German shipowners, has also set its sights on the U.S. markets, setting up a new entity, Mid Ocean Offshore, in partnership with the U.S. entity Mid Ocean, which has experience in U.S. product tankers and, more recently, in LNG barging.

The North Sea has been a hotbed of SOV activity. Norwegian owner Edda Wind operates two purpose-built SOVs, Edda Mistral and Edda Passat, for wind markets. The company stresses the onboard 23m heave compensated gangways to allow technicians to safely “walk to work”. The vessels’ Rolls-Royce design also includes RR “…diesel electric main machinery, consisting of frequency controlled electric driven azimuth thrusters, super silent mounted transverse thrusters, DP2 dynamic positioning system, power electrical system, deck machinery, and the latest generation Acon automation and control system.”

The owner has two more SOV’s on order from at Astilleros Balenciaga, and two SOVs outfitted for commissioning of turbines (CSOVs) from the Astilleros Gondan yard, all for 2022 delivery.

Louis Dreyfus Armateurs, better known as a drybulk market stalwart, has also entered the SOV world with its 84m DP2 capable Wind of Change (designed by Salt Ship), delivered in 2019 from the Cemre yard in Turkey, and recently working at the Godewind project in the German North Sea. The vessel is outfitted with kit from ABB, using the Onboard DC Grid power distribution system. According to ABB, “Onboard DC Grid solution enables variable speed technology to dynamically optimize system energy use in line with the load situation, which results in a 20% cut in fuel consumption. Power from the dual batteries on board will be introduced to maximize efficiency, and the energy stored can come from a variety of sources, including renewables.” Norwegian equipment supplier MacGregor Norway AS provides its Horizon motion compensated gangway and its Colibri motion compensated crane, on the Wind of Hope, a sister vessel. Wind of Change has the Colibri crane and a gangway from Uptime International.

“In terms of conversion of OSV/PSVs one has to look at the wider market. Existing vessels that could be effective candidates for conversion are likely employed in their current mode; those vessels that are not currently employed will be those that are older, less efficient and generally would not easily fit the requirements described above.” - Daniel Holmes, Class BV

“In terms of conversion of OSV/PSVs one has to look at the wider market. Existing vessels that could be effective candidates for conversion are likely employed in their current mode; those vessels that are not currently employed will be those that are older, less efficient and generally would not easily fit the requirements described above.” - Daniel Holmes, Class BV

Conversions

The European market has also seen conversions of existing OSV’s to offshore wind service, with the addition of “walk to work” gangways, motion compensating cranes, and prefabricated accommodation blocks. The Norwegian owner Island Offshore, owner of four “walk to work” boats, has stressed flexibility; the vessels serve oil and gas platforms, but also act as SOV’s for offshore wind. In describing its Island Diligence, delivered in 2018 from VARD Brevik, the company explains that the vessel was originally ordered as a platform supply vessel. But, with wind energy demand growing, they explain that it was “… rebuilt as an accommodation and offshore service vessel with the capacity to accommodate 100 persons on board, maritime crew included, and is equipped with a heave compensated and a 23 m telescopic gangway from Uptime. A flexible offshore crane is also installed, adding lifting capacity and contributing to more flexibility in operations.

Maritime Reporter asked Daniel Holmes, Business Development Manager, North America, Marine & Offshore from Bureau Veritas (BV) about the feasibility of widescale conversions of underemployed offshore oil and gas service vessels for use in the wind trades. He was not overly optimistic. “In terms of conversion of OSV/PSVs one has to look at the wider market. Existing vessels that could be effective candidates for conversion are likely employed in their current mode; those vessels that are not currently employed will be those that are older, less efficient and generally would not easily fit the requirements described above.” He also cautioned that “OSV/PSV conversions require a substantial rework of the structure, new systems, removal of tanks along with complete re-work of the forward accommodation. The required plan review and certification, in addition to the shipyard work, would likely not be an attractive proposition – despite the high cost of U.S. new construction.”

Europe scales up too

European owners have scaled up. In 2018, Østensjø had teamed up with shipowners Wilhelm Wilhelmsen to form Edda Wind, which is now set for an initial public offering of shares. In March, Edda Wind announced an order for two additional CSOVs from the Astilleros Gondan yard. At the beginning of January, the Norwegian stalwart Knutsen OAS explained that it was joining with two Norwegian utilities to form Deep Wind Offshore, a move which would service plots in the North Sea recently opened up by Norway. In March also, another Norwegian owner Awilco- announced that it, too, was joining the fray, with reports that its newly established Integrated Wind Solutions would be ordering crew transport and maintenance vessels.

One possible trend to emerge may be seen from CWind in the crew transfer sector. Its CWind Pioneer, launched in February 2021 from the U.K.’s Wight Shipyard, is a hybrid (diesel/ battery) powered “surface effect” vessel-with a hull form and air cushion system that enables speeds of 43.5 knots, nearly double the speed of typical CTVs. A CWind release says: “The high transit speed of the vessel also means windfarms previously serviceable only by an expensive SOV, can now be reached by the SES CTV within 60 minutes, giving wind farm owners and operators more low cost, low carbon options when determining their transfer strategy.”

Potentially, a wider usage of higher speed CTV’s might possibly reduce the need for larger accommodation spaces of SOVs. Such ideas should be taken seriously.

J.F. Lehman, a leading Private Equity (PE) investor in maritime service providers, has put its money behind CWind’s parent company, Global Marine Group serving numerous offshore segments (including cable laying). BV’s Holmes, in discussing the movement of turbines to deeper waters, along with the shift to floaters, offers another possibility, saying: “…with the acceleration of remote inspection by drones in the coming years could also see SOVs used as drone carriers.”

SOV owners are also looking further into the future towards the transition to cleaner fuels. Østensjø Rederi had acted on “green” ambitions early on, ”… working on developing new technologies based on hydrogen as a safe and efficient energy source.” Its Spanish newbuilds “…are prepared for future installation of this novel technology, which will turn the vessels into zero emission vessels without compromising operational capabilities, i.e. they have endurance to operate on hydrogen throughout their operational cycles,” according to vessel designer Salt Ship. Holmes presented a broad view:“What we see as a classification society is an increased demand for future-proofed designs showing a highly level of flexibility to adapt to future demands,not only in terms of alternative fuel but also how best to accommodate new technologies.”