Help Wanted: Build a New Industry

When Atlantic offshore wind (OSW) projects move into high gear they will kick-start a series of impacts affecting almost the entire East Coast economy, from logistics to transportation to utility projects and, of course, just about every aspect of port and maritime activities.

The related topics of workforce development and employment are among the fundamental issues being pushed and pulled by OSW. How workforce development and education and training proceed – and succeed – will be critical for the U.S. to achieve its huge national goal of 30GW of OSW by 2030, just seven years from now.

This huge energy buildout presents challenges across the maritime sector. Workforce experts use the phrase “adjacent industries” when they discuss worker availability. It means that wind energy companies are likely to recruit employees from more traditional maritime operations since constructing an offshore turbine is completely dependent on maritime skills and expertise. Maritime employers already face a tight labor market; recruitment is a constant effort now. OSW adds new competitive pressures.

Of course, adjacent hiring can work both ways. Now that workforce programs are gearing up to train thousands of individuals in skills directly applicable to many port and vessel operations the entire maritime workforce could see substantial increases. After all, a person trained to work on a vessel may not care if an employer is a towing company or an energy company. New OSW workforce and training programs could help broader maritime industry challenges.

Another factor within OSW development is that employment itself is a major social and policy goal. Federal and state announcements about OSW projects almost always reference new, high-quality, well-paying (frequently union) jobs that pay at a scale that will support a family, not just an individual. Plus, decisions about automation at ports may not always proceed in a straightforward manner since automation can have a big impact on jobs. Port automation has been a high profile and controversial topic within recent federal legislation.

Employment: Seeking focus

On December 1, the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority – NYSERDA – announced a new website “that will empower New Yorkers to become a part of the renewable energy workforce.” NYSERDA writes that New York’s green energy goals – which seeks to develop 9000MW of OSW by 2035 – will “foster at least 10,000 family-sustaining jobs for New Yorkers.”

In New Jersey, the Council on the Green Economy predicts that OSW will result in a net gain of 95,317 jobs from 2021 to 2031.

Employment projections always include some uncertainty, of course. The Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) published a report in September 2022 titled “US Offshore Wind Workforce Assessment.” The report breaks out employment across five sectors –

- Development

- Manufacturing and supply chain

- Ports and staging

- Maritime construction, and,

- Operations and maintenance.

In a closer look at Ports and Staging NREL writes that terminal crews may not expand much because of OSW. The report cites 2018 data when U.S. ports generated 652,078 direct jobs. In 2024 new OSW jobs could number between 300 and 1,100, then maybe increase to 500 and 2,000 in 2030. For ports and staging, NREL writes that OSW will likely add a small fraction to total employment.

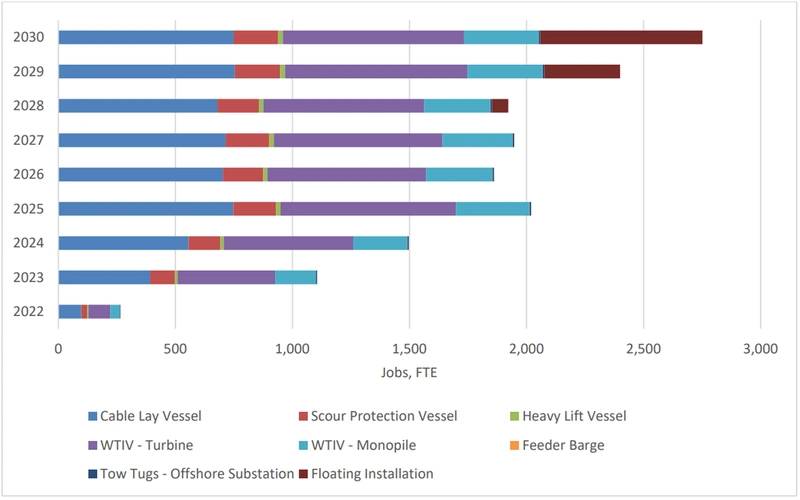

NREL developed a model to estimate onboard employment. In 2024 the model estimates 1,500 new jobs. In 2030, around 2,800 if the workforce is 100% domestic. If the workforce is 25% domestic, the 2024 number is below 500 and 2030 is just a bit above 500. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates there were 75,400 Water Transportation Workers in the U.S. in 2021. BLS doesn’t expect much change in the next 10 years, about 1%.

(Photo: Seafarers International Union)

(Photo: Seafarers International Union)

Training starting – but at what scale?

To meet green energy deadlines for power and employment education and training programs need to start quickly and scale up.

Last September, NYSERDA released a report: “New York State Offshore Wind Workforce Gap Analysis, 2022.” The report includes all occupations associated with OSW, not just direct maritime employment. By 2040, New York projects its OSW employment will grow by 18,000 to 23,000 jobs. Most jobs will be in manufacturing, construction and “induced industries,” i.e., work resulting from employees’ spending their paychecks. New York predicts “severe gaps” in four occupations: plant and system operators, hoist and winch operators, continuous mining machine operators and wind turbine service technicians (Titles are SOC titles – “standard occupational classification”).

In the maritime sector, moderate gaps are projected for marine engineers and naval architects, sailors and marine oilers, and captains, mates, and pilots of water vessels (again, SOC job titles).

New York’s analysis identified 24 wind energy-specific training programs across the State. These are not all specific to OSW, but the training is considered transferable. Most are bachelor’s degree engineering programs. A new OSW program is starting at Suffolk County Community College, but details were not available for New York’s Gap report.

Six programs are in development at various New York institutions. In 2019 and 2020 the report tells that there were wind energy programs available at Clinton Community College and Sullivan County Community College. But only two students completed the program at Clinton. State officials are working on program expansion. The College of Staten Island, for example, recently received $566,000 to help students access OSW training. The announcement doesn’t say, however, how many students are enrolled in programs that likely lead to actually working in the OSW industry.

In New Jersey, university officials are establishing OSW training programs that will range from entry-level certification to associate degrees to master’s degree programs. Susan Nardelli is with Rowan College of South Jersey, one school that is out front on OSW training. Nardelli said programs are still being finalized and adjusted. The school recently purchased and installed training equipment; Maersk Training assisted with this. Rowan’s associate degree program will start in 2024; certificate programs start this year.

It's difficult to get answers about how many students these emerging programs will accommodate and whether the programs are being sized to enroll 25 to 30 students at a time or 250 to 300.

Maritime unions are important training providers. One well-known program is offered by the Seafarers International Union (SIU) in partnership with the Lundeberg Maryland School of Seamanship in Piney Point, Md. This joint program provides free tuition. Courses range from deckhand skills to engine room work to stewards’ duties. There are specific programs aimed at veterans moving from military to civilian work. Graduates work across the industry, from deep-sea containerships to New York ferries.

Bart Rogers was an SIU assistant vice president at Lundeberg (he retired November 30). Rogers was asked whether traditional mariner training meets the needs of OSW employers. “When it comes to the future of the maritime industry,” Rogers commented, “and the clean energy jobs that come with it our school is more than adequate to keep training the next generation of merchant mariners.”

Rogers said crew transfer vessels (CTV) or service operation vessels (SOV) for OSW are similar to vessels such as ferries and tugs. He said the school regularly updates its curriculum to stay current with Coast Guard and industry standards. Rogers added that, “a CTV is very similar to a ferry boat and a SOV is going to be like an articulated barge or tugboat. SIU has been training these mariners for generations.”

Rogers said that new students can be trained in about three weeks to be ready for basic safety skills, lifeboat skills and designated security duties. He said the school has changed its recruiting efforts somewhat so that it can identify potential students living in prospective OSW coastal areas. A parallel focus is on trade schools and community colleges in those areas. Rogers emphasized, though, that SIU’s recruitment is for the whole maritime industry, not just OSW. “We try to over qualify our members,” Rogers said, “so they have more choices where they’d like to work.”

Rogers was asked about expansion and scale-up. He said the SIU program “is always able to increase its capacity to meet industry needs and provide whatever training is required.”

(Photo: Seafarers International Union)

(Photo: Seafarers International Union)

Teamwork, please

Safety training is an issue that exemplifies the mix of forces and issues still at play as OFW moves to the starting gate.

NREL writes that standardized safety training for workers who perform installation and operation activities at sea “has been identified as one of the highest priority areas to address to ensure that an adequately trained workforce is available to build projects.”

Not surprisingly, the U.S. Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) requires the OSW industry to provide training on occupational hazards and risks and mitigate those risks. However, OSHA does not specify training requirements, according to NREL.

Many organizations are seeking safety certifications from the Global Wind Organization (GWO), a nonprofit group of manufacturers and offshore wind energy project owners focused on occupational safety. GWO standards are the most widely adopted in the OSW industry.

GWO estimates that more than 25,000 workers will need to receive basic safety training to meet the installation pipeline through 2025. GWO guidelines are incorporated into training curricula for GWO certified training providers. GWO certification is an important metric and NREL writes that almost 100 community colleges and training organizations are seeking certification. But this process, NREL reports, has proved troublesome. “Many organizations,” NREL observes, “have reported that the process for obtaining (GWO) certification can be long and difficult and have expressed concerns that it could prove to be a bottleneck for training the workforce.” NREL suggests that “efforts should be made to ensure programs can be developed and certified in a timely manner to meet demand without compromising quality.”

NREL’s gap analysis concludes with five recommendations to help expand the OSW workforce.

- Recommendation 1: Build consensus around the roles and requirements needed for an offshore wind energy workforce, and clearly communicate those roles and requirements to all stakeholders.

- Recommendation 2: Continue to conduct detailed assessments of existing programs, trainings, and workers to identify gaps in training, skills, education, or experience. While many land and sea tasks may be similar “working offshore may not be for everyone.”

- Recommendation 3: Prioritize the most immediate workforce needs for training alignment, expansion, and development.

- Recommendation 4: Document existing program offerings and coordinate the development and expansion of programs to ensure these efforts are implemented for the most needed programs and in the most relevant locations.

- Recommendation 5: Encourage collaboration between offshore wind workforce stakeholders to create a diverse, equitable pipeline for future workforce needs.

Job contribution of each vessel type based on the installation hours each person on board works (Source: NREL)

Job contribution of each vessel type based on the installation hours each person on board works (Source: NREL)