Hedging Your Bets

Up and Down brown water bunker pricing is giving small-to-medium sized operators heartburn. It doesn’t have to be that way.

The recent free fall in oil prices is grabbing the attention of many in the commercial marine business. Ferry services, cruise lines, tour boat operators, tugs, etc. all consume significant quantities of fuel to run their vessels. Customarily, the fuel cost is one of the larger slices of pie on the budget chart. Diesel fuel, or “bunkers” as they are often called, is a commodity; a synonymous product traded openly around the world. This factor causes significant swings in the price over the course of time that injects an enormous amount of uncertainty when attempting to predict where that cost is going to be throughout the year. For many stakeholders, fuel represents up to 15% of the total budget. Sudden price spikes – such as the one now in play – can significantly impact the bottom line.

Addressing the Problem

Over time, a variety of methods have been developed to deal with this problem, but most only mitigate the risk to a marginal extent. Some, such as fuel surcharges, are unpopular. Other methods, such as slow steaming or driving up fuel efficiency have certainly helped, but do not offer protection against price spikes. What’s a Mother to do?

Hedging, a term defining the method of offsetting the risk of adverse price movements is a practice that dates back to the early 1600’s when Dutch speculators created an exchange to trade Tulips, of all things. Later, farmers across the globe, including here in the U.S., adopted this tactic to offset the risk of adverse price movements between planting and harvesting seasons. Today, hedging is a common practice for those who trade, buy or sell virtually every commodity known to man. Soft commodity industries like coffee, sugar, and agriculture all participate in some kind of hedging activity. Banks even use hedging strategies to eliminate their risk to slow moving interest rates.

Nevertheless, for so many in the so-called small to midsize end user category, hedging, which can mitigate and often eliminate exposure to price uncertainty, is a misunderstood and opaque phenomena. In reality, the complexity of the practice is overstated, though it makes sense to recruit professional advice prior to engaging in any hedge program.

Hedging 101

Many smaller companies assume that hedging is for the “larger corporations” with vast resources and expertise. But, that’s not necessarily true. Small to mid-size operators can and do run successful hedging programs. So why don’t more players hedge fuel purchases? Does it make sense to have a hedging program active in your company? As it turns out, that depends on how you go about it.

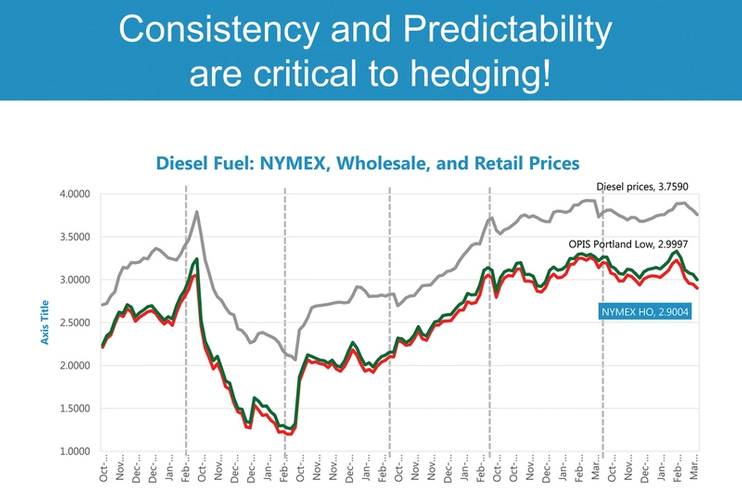

Typically, buyers have a basic understanding of what causes the price to go up and down. The commodity is transparent so that prices can be seen at any given time. The contract, or product, Ultra Low Sulfur Diesel, is traded on public exchanges (CME, ICE, etc.) like the stock market and this information can be easily accessed in almost any medium. It’s also safe to say that the supplier that an operator is purchasing fuel from is reacting to daily price changes and passing them on to the end user. Transparency, the ability for all the parties to view a universal benchmark for prices, is fundamental and essential to preserving confidence in the system. And it is the integrity of the exchanges that allow us to structure a hedge with the highest certainty that it will do the job intended.

The D.E.A.D. Rule

There are critical steps – the DEAD Rule – that should be followed when engaging in any hedge program. The D.E.A.D. rule (Development, Execution, Assessment, Discipline) is critical because if you don’t adhere to these important principles and actions, your program is likely to fail.

Development: First you’ll want to assemble the team that will be making the decisions on execution, providing and reporting on assessment, and maintaining discipline to the adherence of the plan. It is here where vital questions and issues should be answered and defined. What are your objectives? Budget certainty, removing volatility, eliminating the need for fuel surcharging, are typical factors, but there are many variables involved. And, myriad questions to be asked and answered.

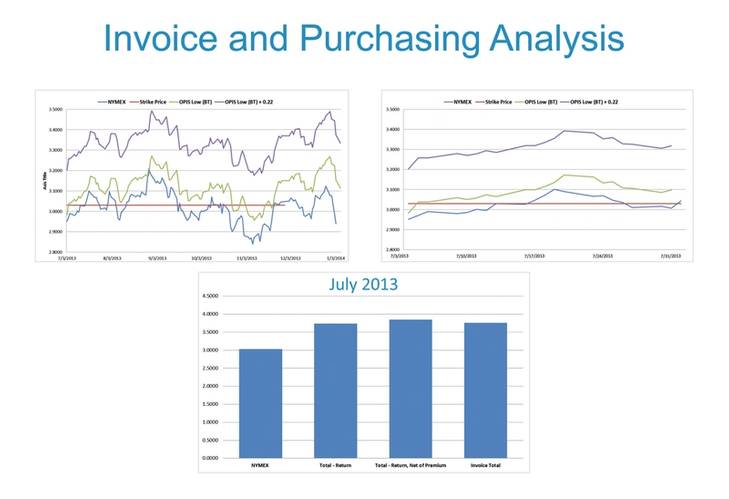

Should you fix the price (no participation if prices fall) or cap the price (ability to procure cheaper fuel if prices fall)? How far into the future do you want to secure pricing? Seasonally, annually, or longer? Who will administer the program? How will you structure the hedges? Will your supplier provide you with options for hedging, allowing you to purchase fixed price contracts or even options on those contracts? What does the structure of your RFP contract look like? How much of your fuel needs will you hedge? All of it or some percentage of it? What will be the timing of purchases and executing hedges? Do you ‘cost average’ over multiple purchases or do you execute all at once based on a certain price level?

The Assessment component involves setting the objectives, establishing best practices, and providing clarity going forward. Execution and Discipline is a bilateral protocol: the significance of these two steps in the D.E.A.D. rule cannot be overstated. The volatile nature of prices changing every day and moving significantly up and down will inject an emotional component that you will want to eliminate. The only way to do this is to have a blue print, the plan you set in the development phase. This will allow you to execute that plan with discipline.

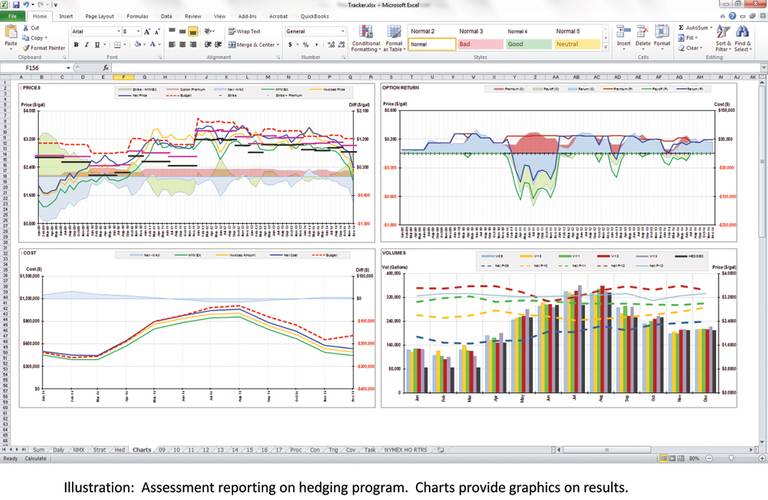

Assessment also involves a tracking or accounting system that is set up in advance and provides a real time view of results, data management functions (actual fuel purchases, paper hedging reporting), and financial reporting. This exercise is essential to the process, providing proof and transparency on how the program is performing. Good reporting boosts confidence in the plan which is necessary to maintaining discipline in the execution of the plan. Most importantly, it documents the results and provides proof that your objectives have been met.

Case Study: Hedging in Actual Practice

A ferry service running several large boats to various islands on an annual basis has a fuel budget that represents one of its largest budget line items. Each year they must forecast fuel prices in order to set their annual budget. When prices rise, it is extremely difficult to get authorization to raise prices in order to meet their budget and hence, performance targets.

In 2008, fuel prices almost doubled in less than 6 months. Even more problematic was the timing – energy prices spiked during the peak travel season. They were forced to implement an emergency increase in fuel prices for the first time in their history. At first they theorized that fixing prices was the only way to manage the risk. However, after witnessing prices collapse at a faster pace than they spiked, they were concerned about the liability of fixing the price outright. This strategy had been considered several times and was also proposed by the fuel provider.

Eventually, this operator considered and eventually implemented a hedging program. Employing the D.E.A.D. rule, a program was set into motion:

This client chose to “cap” their price using an options strategy. This allows them to budget for a price ceiling while maintaining the ability to participate if the market drops, something that cannot be done if the price is fixed. A new RFP process was built around a transparent price benchmark, managing vendor selection, and executed options trades. Now in their sixth year since the inception of the program, the client continues to demonstrate remarkable discipline when it comes to execution. Their reporting system gives them absolute clarity on the results which in turn gives them the confidence to execute and stick with their long term strategy.

What About Now?

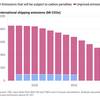

With fuel prices at their lowest in nearly six years, it makes sense to at least consider hedging current levels into your budget for the near future. That said; a look at the 20-year fuel pricing chart provokes further thought to how to go about it. The chart reveals clear evidence that prices are not only unpredictable but they typically go down faster than they go up, yet when prices do go up they tend to stay up longer. This is why it is important to understand how to cover risk without actually taking on more exposure.

If higher fuel prices will impact your bottom line, cause your company to be uncompetitive, or create other issues, then you should look at the cost/benefit of a hedge program. Any company, no matter the scope, can hedge its exposure. When measured by fuel consumption, this can involve those that use as little as 30,000 gallons and as much as 20 million gallons annually; proof positive that anyone can realize the benefits of a well thought out hedge program.

About the Author

Richard M. Larkin is President of Hedge Solutions, Inc.

(As published in the March 2015 edition of Marine News - http://magazines.marinelink.com/Magazines/MaritimeNews)