Cargo Sits Waiting a Fortnight in Asia: Analysts Seek Reasons

Jochen Gutschmidt, head of global transport procurement at Nestle, asked the Global Liner Shipping Conference in Hamburg last week: “Why is cargo waiting in Asia for two weeks?” Using data from Drewry’s latest 'Container Forecaster', just published, this week’s 'Container Insight Weekly' attempts to answer that question and quantify how much capacity has been taken out of the system by slow steaming and lay-ups.

Slow steaming

There was a time when vessel optimisation was achieved by simply deploying the biggest ships at full speed so to minimise the number of vessels required. It was a rare example of a win-win scenario for carrier and shipper, aligning carrier profitability with service quality in terms of fast transit times.

The global financial crisis and hugely inflated fuel prices shattered those bedrock assumptions of how to operate liner services and ever since it has been much more cost effective to operate more ships at lower speeds.

Slow steaming (combined with additional ships being phased into loops) was first adopted in the Asia-Europe trades and then gradually expanded from early 2009 into the transpacific and several north-south routes. Carriers quickly realised the fact that as well as reducing voyage costs, slow steaming offered a way of managing the vessel surplus that was building up as demand shrivelled.

In the pre slow steaming era Asia-North Europe services deployed an average of eight ships, whereas these days the average has extended to 11 ships as round voyage speeds have slowed to about 17 knots, well below the 24-25 knots the vessels were designed for.

Longer round voyages require extra ships. Approximately 250 vessels, averaging a little over 11,000 teu, are currently needed for 22 weekly westbound Asia-North Europe services. If slow steaming had never happened and services in that trade were still running with eight ships rather than 11 then only 180 ships would be needed to maintain the same number of loops, meaning carriers have effectively absorbed 70 or so ships in that trade alone.

Idled vessels

To lay-up a ship is a last resort option as most carriers prefer to keep ships trading even when conditions are so bad that cargo is not fully compensating direct costs. But when all else fails, owners finally have to accept that lay-up is the ultimate fall-back position. This was most strikingly the case in 2009 when nearly 10% of the total fleet (in teu terms) was parked.

The idle fleet (defined as vessels not attached to a service for 14 days or more) is taking a much smaller bite out of the global fleet than it was in the industry’s annus horribilis. Drewry estimates that the idle fleet is now equivalent to around 3% of the cellular fleet with the non-operating owners baring most of the pain.

Net impact on effective capacity

Slow steaming and idling were the inevitable consequences of the downturn as carriers had to put an end to the cash burn that was making bankruptcy a very real prospect for many. Most carriers are still losing money despite the costs savings from lower bunker prices and fuel consumption so their capacity management cannot be considered a complete success, although the insistence to carry on ordering big new ships is the prime hindrance on that front.

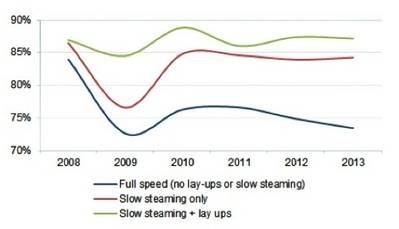

The net result is that total effective capacity has only grown by 22% since 2008, whereas at “full speed” the global capacity would have grown by 40% over the same period. In 2013 alone, slow steaming and lay-ups reduced available supply by nearly 3 million teu.

The impact on aggregate ship utilisation (and subsequently freight rates) is the difference between vessels being close to 90% full rather than only being three-quarters full. Missed voyages also temporarily inflate load factors with Drewry estimating that throughout 2013 blank voyages cut monthly one-way capacity in the Asia-North Europe trade by an average 2.5%. Depending on the severity of the missed sailing program it added as much as five points on to our assessment of headhaul load factors.

Put all these factors together and the chance of cargo roll overs in peak cargo months is greatly increased. Through the sub-optimal deployment of assets carriers have been relatively successful in reducing voyage costs and raising ship utilisation. However, this policy is at times excessive and detrimental to shippers.

Drewry's View

Carriers have done a good job of absorbing excess capacity into the system but the foundations of their “recovery” are rooted in inefficiencies and as such are fragile. The large orderbook means they will need to intensify their efforts and shippers should prepare for longer transits and more frequent use of blank voyages.

Source: Drewry Maritime Research

http://www.drewry.co.uk/publications/