Transportation electrification (TE) is starting to impact California like no other state, maybe unlike any other place in the world. Essentially, and eventually, TE depends on replacing gasoline and diesel engines with renewably generated electric power. This could include just about every car, truck, fork lift, drayage vehicle, train and ship in California.

For the freight industry, including the maritime sector, TE presents complex challenges. In recent months, CA has started wrestling with “heavy-duty” freight transportation electrification. The maritime industry is included in this heavy-duty focus, starting with container, passenger and refrigerated cargo vessels. TE presents new demands across the board for ships, terminals and port operations.

The 7,500-acre Port of Los Angeles is center stage for zero-emission and low-emission technologies and strategies. Environmentally, the Port wants to be a better neighbor, decreasing the air pollutants that impact nearby communities. Additionally, the Port needs further controls to help Southern California meet Clean Air Act requirements for ozone, or smog, and fine particulates. The Port and its commercial operations need to decrease CO2 and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. By 2030, California wants state-wide GHG emissions to be 40 percent below 1990 levels. Freight sector reductions are critical for hitting that target.

A Work in Progress

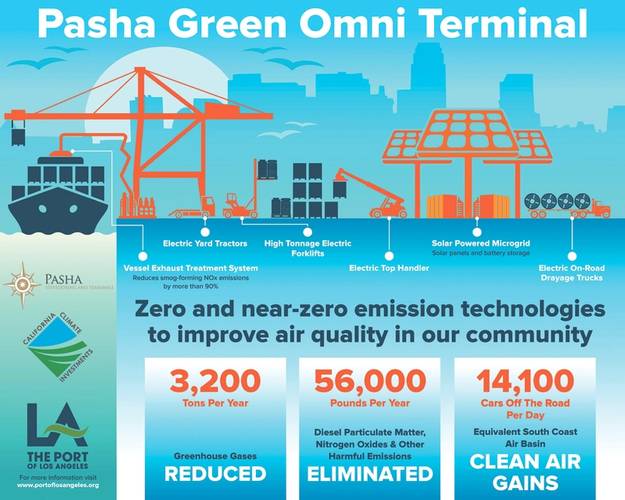

Figuring out how to do this remains a work in progress. But a demonstration project is starting at LA’s Port, in partnership with Pasha Stevedoring and Terminals L.P., The Green Omni Terminal Demonstration Project is a year-long, public-private effort to show full-scale, real-time zero and near-zero emission technologies at a working marine terminal.

At full build out, Pasha will be the world’s first marine terminal able to generate all of its energy needs from renewable sources. For example, Pasha will integrate a fleet of new and retrofitted zero-emission electric vehicles and cargo-handling equipment into terminal operations, including four electric yard tractors and two 21-ton electric forklifts. Partially funded by a $14.5 million grant from the California Air Resources Board (CARB), the total cost is $26.6 million. Pasha committed $11.4 million in cash and in-kind participation, as well as serving as the project site.

For mariners, there are two critical components within this maritime/transportation electrification effort. One is likely familiar: using shore based power while at berth so that auxiliary engines – and emissions – are cut. The Port calls this Alternative Marine Power (AMP); more generically it’s called ‘cold ironing.’ The LA Port has 270 berths, 24 are AMP equipped. This has been around for quite a while, actually.

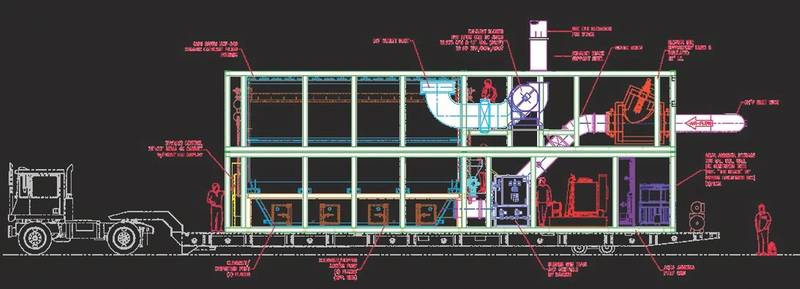

The second component is perhaps less familiar. It consists of a dockside vessel emissions capture and treatment system – called ShoreKat, developed by Clean Air Engineering – Maritime (CAEM), in partnership with Tri-Mer Corporation. ShoreKat is next-generation technology, based on an older CAEM system, a barge-mounted unit called Marine Exhaust Treatment System-1, approved for use by CARB in June 2015. ShoreKat will work in tandem with on-shore power. It will be required to control stack emissions – under certain circumstances – for ships which, for one reason or another, cannot use shoreside power and need to keep auxiliary engines running.

Prior to entering Port, a captain will need to have made his decisions about at-berth power. He can cold-iron the vessel, assuming compatibility with the terminal, and that the ship is retrofitted for shore-side power. Or, he can remain powered-up. But in that case the vessel needs to be connected to an emissions capture system.

Capture, Treat - & Sell?

CAEM reports that the newer ShoreKat controls are more expansive than METS-1, capturing and treating more than 90 percent of PM, NOx, SOx and related diesel pollutants. ShoreKat can eliminate upwards of a ton of NOx emissions per vessel per 24-hour period.

ShoreKat offers two additional advantages over METS-1. Land based, ShoreKat is placed on a trailer, able to move along a pier, facilitating best position for subsequent loading and unloading. A crane lifts a “bonnet” to attach to the vessel’s exhaust stack. Treatment can commence without vessel retrofit. Importantly, ShoreKat has lower capital and operating costs compared to METS-1. ShoreKat’s second advantage pertains to reducing energy-related emissions, particularly CO2, a top goal, obviously, for transportation electrification. CO2 reductions will be part of the demonstration work at Pasha, the first time that CO2 destruction technologies will be applied at a seaport terminal.

Matt Wartian is a Regional Global Practice Manager the engineering firm Burns & McDonnell and the project manager for Pasha/Green Omni. The CO2 control research has two parts; determining best ways to maximize CO2 reductions and in a later phase, planning for CO2 capture, for disposal or, perhaps, sale to a downstream user for research.

Wartian expects ShoreKat to be ready by February 2017. Although vessels will not be charged during the demonstration, planners still need to decide how ShoreKat costs will be covered after start-up. For example, today’s ‘cold-ironed’ vessels must pay for shore-side power.

California: out in front again

This is not just a marginal, academic research project. For example, two new CARB documents exemplify how regulations will push TE compliance using shore-side power and/or control technologies.

One document is a “Vessel Fleet Plan” that requires operators to detail how their fleet will comply with at-berth emission requirements. The Port’s initial focus is on container and refrigerator fleets, and then only those which “cumulatively make 25 or more visits annually to a California port.” For passenger ships, the minimum is 5 or more visits. And, while LA is today’s target, the expanding regulations will eventually apply to of state’s larger ports.

These Plans were due to CARB by October 1, 2016. As a counterpart to the vessel plan, terminal operators must also explain how they will fulfill their obligations under the environmental initiative. A second, newer policy is an Advisory posted in November. The Advisory informs affected vessel fleets and terminal operators as to how the Air Resources Board (ARB) will proceed with enforcement of the regulations, beginning in January 2017.

The Advisory sets forth six possible scenarios in which a vessel might be granted some leeway regarding at-berth emissions. These could include unavailability of terminal power, unresolved hardware problems, or when vessels keep power, but use an alternative control technology. Whatever the reason, operators are required, annually, to report specific vessel and event-related information to CARB. Operators are liable for infractions, fines and penalties could follow. In 2017, 70 percent of a fleet’s visits must comply with the Advisory’s requirements. That increases to 80 percent by January 1, 2020.

Looking Ahead

Matt Wartian was asked about scale-up, at least at LA. After all, the Port of LA is the 19th largest in the world, the 9th largest when combined with the Port of Long Beach. LA was visited by 1,951 vessels in 2015. Unanswered questions include how much AMP infrastructure is needed, how many ShoreKats that might involve and who will pay for it all. Wartian himself doesn’t know. That said; there will only be one ShoreKat at the Pasha project. The Pasha terminal is a break-bulk facility and usually unloads just one ship at a time; so operationally, that works. As the emission reduction program expands, though, to other terminals, and other Ports, the “right number” of units – AMP and ShoreKats – still needs to be determined.

The Port of LA has no plans to expand AMP beyond the current 24 berths, which cost the Port about $180 million. As a comparison, the ShoreKat used in the Pasha project cost $3.7 million. Demand – and future investments – will likely become clearer for vessel and terminal operators, and the Ports themselves, when compliance plans can be reviewed.

In many ways, transportation electrification is hardly about transport. In California, TE is about using electric power primarily to replace individual engines and power plants. TE is not being advanced because it offers better, more efficient or safer transport. Furthermore, because TE results from command, not demand, it sweeps in new regulations and enforcement to ensure participation, compliance, equity and, eventually, the data that will document improved air quality and reduced climate impacts.

Hopefully, these non-transport goals will still allow safe, efficient and cost-effective maritime shipping.