Small Boat Construction Using 3D Modeling

Pilot Project

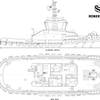

It took fewer than two man-weeks to complete the detailed engineering design, including working drawings for some 250 individual parts using ShipConstructor. These were intended for the manufacture of a series of three 22 ft. patrol boats. Prior to parts manufacturing, a full 3D structural model of the vessel was created to ensure there would be no part match up problems at the time of assembly. Also known was the exact hull weight and the total length of peripheral cuts of all plate parts, which is important to estimate the cutting time. All curved plates had been lofted electronically and expanded to flat patterns, then coded to NC machine code. The parts manufacturing was done with a CNC high speed milling method, where the dimensional accuracy of the parts is in the range of ± 0.005 in. Both metal and none-metal materials were cut for this project. Due to the precision of the lofting and the cutting, three full ship-sets of all parts were manufactured ahead of time. None of the parts had any allowance for trimming, even though this particular hull had never been built earlier. All plates were marked to simplify joining parts. ShipConstructor provided exact nesting. All data on the nest plots and in the report was automatically kept up-to-date.

Assembly

Due to the exact fit, the parts could be assembled without the use of jigging. This special method works by beginning with the bottom shell plates being joined at the keel starting from the aft end. While doing so, the plates automatically obtain the correct shape. Installing longitudinal stringers, frames, hull sides, and decks at the marked positions follows this process. The entire hull is tacked together, and stitch welding is performed in selected places. The sheet metal crew was familiar with the thermal characteristics of aluminum, and with limited guidance was able to assemble three vessels without having to trim any parts or force fit any components. The weld joints were accurate everywhere producing ideal conditions for welding.

Review

Many manufacturers underestimate the costs of correcting mistakes occurring involuntarily during the design and manufacturing process. These costs often exceed the cost of taking preventive measures to minimize errors. Oetter and Bjornert chose to introduce the engineering software package ShipConstructor developed by ARL, which permits working in a conventional 2D drafting mode. However, this program automatically produces a 3D structural model, calculates weight, CG and provides material estimates and other documentation from a single database from the working AutoCAD drawings. This virtually eliminates human errors, and the elimination of rework is evident by experiencing timesavings in excess of 40 percent over the use of conventional shipbuilding methods. An additional cost benefit is one can reduce the needs for experienced boat builders, as long as there is knowledge of the thermal behavior of aluminum and having access to precision made parts. Victoria Shipyards was not the first group to use this approach. This process has been used in a number of previous programs with similar results. The advantages of machining aluminum, instead of plasma arc or water jet cutting, is the edges of the parts do not need any further finish or dressing before assembly. Raw edges, with surface imperfections or nicks would cause stress concentrations and significantly encourage surprise and premature fatigue cracking. The benefit of reduction in Quality Assurance inspections with minimum rejection and rework is obvious. "This approach to engineering and manufacturing will also work well in larger programs where modular construction is used," said one Victoria Shipyards worker. Rolf Oetter is president of Albacore Research Ltd. Rolf Bjornert is employed by M Sc Engineering.