Ballast Water Update: Weighing the Advent of VIDA

The hard-fought passage of VIDA promises a simpler, more unified and logical set of environmental standards related to the discharge of myriad vessel streams. Industry wanted it, and now it is here. Will it deliver, and if so, when? That depends on who you talk to.

As most commercial maritime operators know, US ballast water regulations made a sharp turn last December. That’s when President Trump signed the Frank LoBiondo Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2018.

That legislation contained Title IX – the “Vessel Incidental Discharge Act (VIDA),” a welcome legislative goal among many maritime business trade groups who had long complained that US ballast water regs were such a confusing mix of directions and requirements that compliance was almost impossible. Until now, ballast water and with it, the issue of invasive species, has been controlled on numerous regulatory fronts: through EPA’s vessel general permits (VGP) and the Nonindigenous Aquatic Nuisance Prevention and Control Act and the National Invasive Species Act as well as other U.S. Coast Guard and clean water legislation provisions. Beyond this, almost twenty states further ‘Balkanized’ the critical issue by forming individual local statutes, each different in their own, obscure way.

Congress, with VIDA, ripped out this regulatory tangle. By 2022, at the latest, the VGP will be gone, as will aquatic nuisance and invasive species legislation (at least as it pertains to vessel discharges). Instead of a permit, discharges will be controlled via regulations. [Note: until this new work is finished all existing permits and regulations remain in place and in force.]

Examining VIDA

To get there, VIDA first requires EPA to develop new “Federal standards of performance for marine pollution control devices for each type of discharge incidental to the normal operation of a vessel.” Discharges, of course, can include anything from bilge water to firemain systems to boat engine wet exhaust to ballast water. VIDA discharge standards are due by December 2020. What can you expect? Currently, the VGP addresses 27 vessel discharges. An EPA spokesperson, in an email, said that “EPA anticipates that the majority of the discharges for which VIDA standards will be developed will remain the same.”

It isn’t getting any easier: The 27 discharges outlined in the 2013 Vessel General Permit:

Bilgewater/Oily Water Separator Effluent | Sonar Dome Discharge | Deck Washdown and Runoff |

Anti-fouling Hull Coats/Coating Leachate | Welldeck Discharges | Aqueous Film Forming Foam (AFFF) |

Oil Sea Interfaces (props, tubes, etc.) | Fish Hold Effluent | Boiler/Economizer Blowdown |

Motor Gasoline, Compensating Discharge | Elevator Pit Effluent | Equipment Subject to Immersion |

Refrigeration & Air Condensate Discharge | Firemain Systems | Gas Turbine Washwater |

Distillation and Reverse Osmosis Brine | Freshwater Layup | Non-Oily Machinery Wastewater |

Graywater Mixed with Sewage from Vessels | Cathodic Protection | Seawater Piping Biofouling Prevention |

Exhaust Gas Scrubber Wash Discharge | Chain Locker Effluent | Boat Engine Wet Exhaust |

Seawater Cooling Overboard Discharge | Ballast Water | Underwater Ship Husbandry |

Then, VIDA requires the Coast Guard to take EPA’s new discharge standards and develop “regulations governing the design, construction, testing, approval, installation, and use of marine pollution control devices as are necessary to ensure compliance with EPA’s standards.” Deadline: December 2022.

Generally, VIDA does not apply to recreational vessels or small vessels (less than 79 feet in length) or fishing vessels. However, small vessels and fishing vessels are NOT excepted if they discharge ballast water!

Readers will likely note that there are a number of issues going on here all at the same time. Critically, VIDA is not just about ballast water – it’s about all of the discharges covered by the VGP, and maybe more (although much of this report is focused on ballast water). And, while the typical workboat in U.S. waters isn’t impacted by ballast water regulations, that’s also not always the case.

Additionally, concurrent to VIDA’s Congressional development, the Coast Guard has been working frantically to certify ballast water management systems – the equipment and processes that vessel operators can invest in with the confidence that those systems will comply with current ballast water standards.

Importantly, whatever new discharge standards EPA and the Coast Guard eventually establish, those standards cannot be less stringent than current requirements for effluent limits and requirements for various types or classes of vessels.

Congress’ goal with VIDA is the development of national uniform vessel discharge standards, a system to replace today’s fragmented system that places varying demands literally from state to state. VIDA’s implementation is a marriage of existing vessel discharge policies with the Act’s new demands. VIDA’s starting line is within an already swirling set of issues. As noted, EPA and the Coast Guard have less than four years to make very choppy waters into a serene, placid and predictable stream. That won’t be easy.

VIDA is not just about ballast water, but ballast water does receive singular, focused attention within VIDA. The Act requires, for example, a captain to conduct a ballast water exchange or saltwater flush prior to calling on certain US ports. It requires proper maintenance and performance standards for ballast water management systems (BWMS) and requires a “valid type-approval certificate” for that system, similar to current requirements.

Notably – and of great importance to individual U.S. states – VIDA allows state and regional interests to participate in standards development, although the Act keeps final decisions within EPA and the Coast Guard. Another important concept: VIDA seeks to “preserve the flexibility of States” regarding program administration and enforcement.

Outreach & Engagement

One initial, general focus for both the EPA and the U.S. Coast Guard, in the first six months, has been stakeholder outreach and engagement. The agencies have developed two interactive webinars presenting an overview of VIDA, providing a chance for people to ask questions and comment on future program development.

Captain Sean T. Brady is the Chief of the Coast Guard’s Office of Operating and Environmental Standards (OES). Brady’s office is responsible for developing the maritime regulatory standards required by international treaties and U.S. statutes, regulations, and policy. In an interview, Brady said that his office and EPA have been working together since December, discussing and planning how to best move forward. He said that each Agency has a “VIDA team.” These teams meet weekly, usually via teleconference.

Brady noted that EPA and Coast Guard regulations can be similar, but different enough to make compliance difficult. “Regulatory consistency,” Brady said, “reduces risk for the commercial industry. We feel that it’s just as important to develop a consistent program as it is to develop an effective standard.”

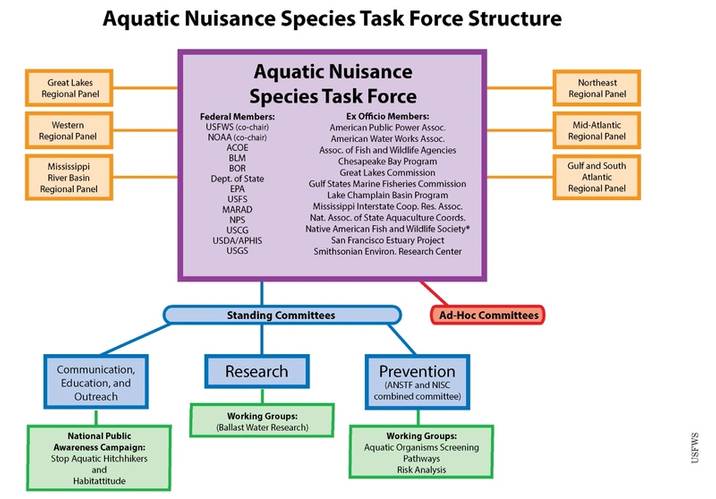

These initial, general planning efforts are important. VIDA requires cooperative work with state governors as well as formally established advisory bodies, such as the Great Lakes Commission and the Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force. But VIDA also makes specific demands as implementation starts.

One important initial work product is publication, by the Coast Guard, of a draft “policy letter” describing “type-approval testing methods and protocols for ballast water management systems.” This draft will address nonviability of organisms in ballast water as well as system performance and laboratory certification.

This is critical work. The draft letter was due 180 days after VIDA’s enactment – around June 4. The document is late: still unavailable by mid-June. Stakeholders should watch for its release because that starts a 60-day public comment period. Issues needing evaluation include how the draft aligns (or not) with IMO (International Maritime Organization) requirements. Other issues could reference UV efficacy and verification, and use, of “most probable number” analyses referencing phytoplankton and other biota.

The letter will include EPA’s test protocols and new standards. For ballast water, it will serve as the basis for a final policy regarding “type-approved” treatment systems, which needs to be in place one year after VIDA’s enactment, or December 2019. Brady adds, “Systems already type-approved by the Coast Guard will retain their approval. We do not expect to address the status of or include a discussion on existing systems in the policy letter.”

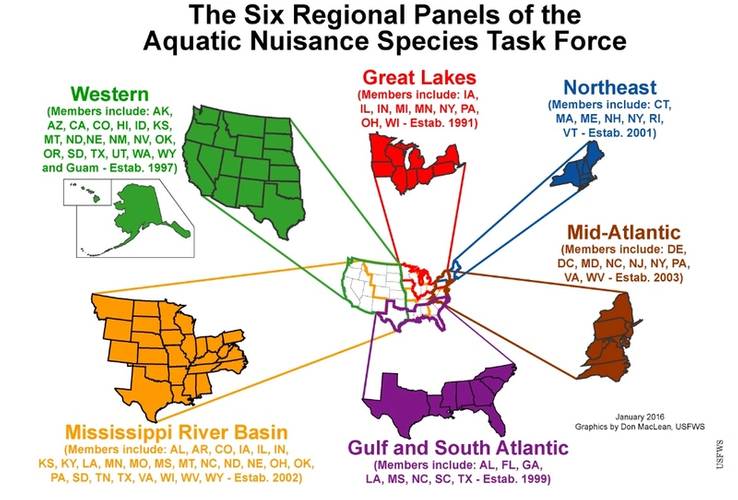

Although there is no date for its start-up, another important VIDA requirement is establishment of an “Intergovernmental Response Framework” to respond to nuisance species risks from ballast water and vessel discharges. This will include tracking invasive species, evaluating specific risks and establishing emergency best management practices for rapid deployment in a specific locality or region. This is to be coordinated through the federal Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force (ANSTF) which includes representatives from numerous federal agencies, as well as ex-officio members, from the American Water Works Association, for example, and the Great Lakes Commission. Six regional panels advise the larger Task Force.

Brady said a focus on this Framework is starting now but he added that these next steps depend somewhat on the proposals within the forthcoming draft policy letter. Importantly, this response Framework is linked to new ballast water reporting requirements to be filed with the National Ballast Information Clearing House. The reports will serve as the basis for an annual report evaluating “nationwide status and trends” relating to ballast water delivery and management and “invasions of aquatic nuisance species resulting from ballast water.”

That first annual report, authored by the coast Guard in conjunction with the Task Force and the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), is due July 1, 2019. It’s not clear whether that first report will be ready on time. SERC officials did not reply to questions about their work.

The Great Lakes

As one might expect, the Great Lakes Commission (GLC), based in Ann Arbor, MI, is one major regional group keeping a close watch on initial VIDA/ballast water implementation. With invasive species, particularly for the Great Lakes, there’s usually no second chance – clean up and remediation are poor substitutes compared to preventative diligence. GLC, established in 1955, includes the eight Great Lakes states; Ontario and Quebec are associate members.

VIDA does provide a mechanism for Great Lakes governors to propose and implement “enhanced standards and requirements.” But it’s not a quick and direct process and the costs associated with a new standard have to be considered. For higher compliance costs, each Great Lakes governor has to endorse the proposed standard. If compliance costs do not increase, just five of the eight governors need to endorse. Depending on point of view this can seem too slow and clumsy. On the other hand, it prevents governors, perhaps facing internal state pressures, from casually taking on a process with very complex science.

Darren Nichols is Executive Director of the Great Lakes Commission. As VIDA moves forward, Nichols said that GLC is evaluating how it can best influence upcoming ballast water policy decisions. A top priority is a “constructive binational dialogue.” Canada’s ballast water regulations align with the IMO, not the U.S. Coast Guard. Nichols wrote in an email reply to questions that it’s unclear to the Commission “whether and how the two federal governments are working together toward a harmonized outcome in the Great Lakes.” One idea GLC is considering is a conference with EPA and the Coast Guard to “explore where there may be areas of consensus among key stakeholders” before “proposing a formal national standard.”

It is GLC’s contention that dual federal rulemaking is unlikely to provide a comprehensive solution to ballast water within the Great Lakes basin. The GLC Board of Directors seeks a “harmonized, binational approach since the waters of the Great Lakes are not limited by political boundaries.” Regarding process, GLC thinks that solving ballast water issues will require a “more nuanced dialogue” than exists within standard public comment processes, e.g., the 60-day window that will follow the draft policy letter.

Nichols writes, “Ballast water is a policy that has in many ways eluded the Basin for decades and one that is worth getting right. The Commission strongly urges the US and Canada to find a way to work together with the Great Lakes Basin community to develop smart, durable and consensus-based policy solutions for vessel discharges.”

A Good Start?

On the industry side, the American Waterways Operators (AWO) has long been involved in ballast water policy. AWO led the industry coalition supporting VIDA’s passage, citing the benefits of a uniform, national program. Jennifer Carpenter is AWO’s Executive Vice President & Chief Operating Officer. It’s her assessment that EPA and the Coast Guard are off to a good start with VIDA implementation. “We’re very encouraged by what we’ve seen,” Carpenter said, citing “excellent cooperation and communication” between the two agencies. As an example, she cited the recent EPA/Coast Guard VIDA listening session at the US Merchant Marine Academy.

Carpenter said that VIDA implementation offers the Coast Guard and EPA a chance to prioritize management practices that can provide better payoffs for environmental protection and vessel operators’ time and resources. She noted, for example, that with barges, the VGP requires a weekly vessel inspection that must be documented every week and reported to EPA annually. If a company owns 100 barges, that generates over 5000 reports per year, a filing deluge not likely helpful to anyone. She hopes that VIDA implementation results in a program focused on pollution prevention, establishing big-picture indicators of progress and success, based on streamlined and efficient compliance requirements from marine businesses.

That’s a great set of goals. The clock is ticking.

This article first appeared in the July 2019 print edition of MarineNews magazine.