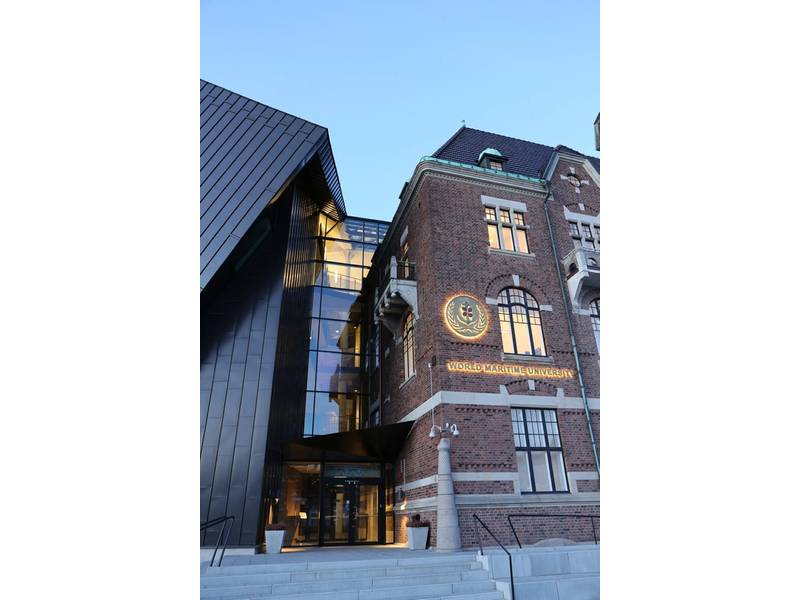

Profiles in Training: Dr. Michael Ekow MANUEL, Professor, World Maritime University

The global seafarers crisis takes center stage at the World Maritime University (WMU), as Dr. Michael Ekow Manuel discusses the importance of seafarers, seafarer training and the MarTID 2021 survey.

While many maritime professionals have the theoretical ‘salt in their veins’, a career at sea seemingly predestined by family ties and/or geographic proximity, that is not the case for Dr. Michael Manuel, Professor, WMU. Hailing from Ghana, Dr. Manuel from a young age had a fascination with vehicles and everything that moves, but ships were not his focus, rather airplanes. “It was relatively later on in my teen years that I was exposed to shipping, and I became interested in the technical side of it, the fact that these are the largest moving things that man has made,” said Dr. Manuel. “Once I got into it I was exposed to other aspects beyond the machinery: the education, the cargo and safety-at-sea. Finally, I ‘dropped anchor,’ so to speak, in this industry.”

Dropping Anchor in Maritime

Today Dr. Manuel works at WMU as a Professor (Nippon Foundation Chair for Maritime Education and Training) and is also the Head of the Maritime Education and Training Specialization of the University, focusing on educational policy and governance as well as organizational behavior and leadership. He and his colleagues at WMU teach and mentor masters and postgraduate level students from all over the world in regards to maritime governance, policy and leadership. “The students are mainly individuals in their middle career, middle and senior management levels who have come to join a network that speaks the same language around maritime governance,” said Dr. Manuel. “It starts off with the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) goals in terms of safe, secure, and sustainable shipping. However, maritime governance as a whole in the context of international public policy is where the development of critical skills is targeted”

To be clear, the WMU is not a seafarer training institution; it is a postgraduate university which was set up under the auspices of and is an institution of the IMO. “We educate the people who then go back to their individual jurisdictions and oversee the international and national frameworks that govern, for example, the training of seafarers,” he said.

Though Dr. Manuel was not born into the industry, one would be hard pressed to find another maritime professional as passionate or dedicated to all matters maritime. And while his career has taken the path toward academia, he flourished during his career at sea, a critically important piece to his experience that has helped to shape his involvement in maritime education and training.

“My first training at sea was in the context of a national line. There were a lot of people onboard the ship, which created a great environment for training because the crew were not overwhelmed with too much work,” said Dr. Manuel. “You had all sorts of people that would challenge you in every space when it came to your education. In contrast, by the time I was leaving (seafaring), a ship double the size and with a wider scope of operations had half the crew.”

Seafaring, and the way in which seafarers were trained, was changing rapidly.

“In my training days as a cadet, the chief officer recognized his/her role as a trainer, and made the effort to manifest that role,” said Dr. Manuel. “In contrast, my last commercial ship was a big container RoRo ship that was on a very tight schedule, quickly in and out of ports with lots of work for all. It was difficult to create an atmosphere for training, for cadets in particular, and even sometimes for the officers.”

The Tech Transition

Today is a transcendent period in maritime history, as decarbonization, autonomy and automation, and digitalization all conspire to help shape the near- and long-term future for the way in which the world moves the vast majority of its goods.

Training, too, is at a crossroads, as owners, maritime education and training institutions and seafarers alike depend on increasingly sophisticated simulation technology to help teach skills that were once the province of learning by doing at sea.

“Today there has been a transition to using technology more and more to aid training,” said Dr. Manuel. “Simulation has become a greater point of emphasis, and there are ships today that even have simulators onboard specifically for training. The emphasis on onboard practical learning is being challenged because the fidelity of simulators is improving. One can gain competencies related to many practical tasks, particularly in the context of bridge work, on shore, in a school, which was hitherto only possible onboard ship. This kind of onshore exposure makes it easier when you are onboard the ship. You can use the ship to train on other things that are not possible in simulation. Nevertheless, it can be argued that many parts of onboard training remain valid and necessary for the development of a comprehensive range of skills”.

The trend toward increased automation onboard ships to help effectively reduce crew headcount and crew costs is hardly a new trend, with ships growing larger and more automated and crews growing smaller in number over the past 30 years. However, the last 12 months and the COVID-19 pandemic have served to effectively fast track a number of digitalization initiatives, including the delivery of training to seafarers. “You see this macro trend of the increasing “invasion” of technology into the realm of training, and in the last few months, we have seen how COVID has accelerated this trend, for example with cloud-based simulation,” said Dr. Manuel.

The Seafarer Crisis

Seafarers, arguably, have shouldered as much if not more burden than any other profession (with the exception of health care workers). Tasked to deliver an estimated 90% of the world’s cargo – including food, healthcare materials and equipment, and energy, to name a few – many seafarers’ lives have been literally upended with the inability to effectively conduct routine crew changes, leaving hundreds of thousands stuck on ships, contracts expired, with no ability to return to families and homes. Similarly, seafarers shoreside have been unable to embark ships and earn a living.

“Greg, I must say this situation worries me, and in fact it worries all of us at WMU,” said Dr. Manuel. “Seafarers have not been treated well at all by the majority of states, companies and stakeholders, and sadly this only accentuates an existing problem. Seafarers have seldom been recognized for their contribution to the world, to commerce and the global economy.”

IMO, WMU and a chorus of leaders across the maritime sector have been demanding a solution for more than 12 months, yet still today less than 50% of the port states have taken the simple step of declaring seafarers as key workers.

“COVID has also had impacts on things like training, the extension of seafarer contracts, the conditions in which seafarers live as well as their mental wellbeing,” said Dr. Manuel. “You have people staying on ships for extended periods of time in a manner that is almost inhuman, yet corridors are opened for other people who are nowhere near what one would term as ‘key workers’.”

While there are a multitude of immediate concerns – starting with seafarer mental health and well-being, as well as ship safety – the long-term implications could be even more dire. “People will start finding alternate avenues for employment, and I fear that the repercussion could be a marked decrease in the desire for people to go to sea,” said Dr. Manuel.

- The MarTID Survey

- For the past four years, WMU, Marine Learning Systems and New Wave Media, publishers of Maritime Reporter & Engineering News, have been engaged in collecting data from ship owners/operators, maritime education and training institutes and seafarers, a non-commercial endeavor that is available for free, to all, upon publication.

- “The Maritime Training Insight Database (MarTID) fills a void that's been in existence for quite some time. There's no real context within which you have this kind of data where we are trying to collect the insights from those diverse stakeholders,” said Dr. Manuel. “They bring their views so we can better understand some of the issues that are not addressed by legal convention. For instance, training budgets: What kind of specific learning activities are being employed? What's the trend in, for example, online learning in terms of training for the seafarer?”

- With COVID still raging globally, the 2021 MarTID survey is arguably more important than ever, and this year there is a section of the survey that is dedicated to COVID.

- “The idea is to have a repository of data that allows us to analyze trends, inquire into best practice and freely share that best practice, because this is a non-commercial, not-for-profit endeavor,” said Dr. Manuel. “With this we can learn from one another and have this kind of discourse that has the aim of improving training, and thereby improving conditions in shipping safety, the IMO goals, and the global maritime goals. This year, in particular, we are keen to hear from all stakeholders about how training has been affected by COVID.”

- Take the 2021 MarTID survey of maritime training practices:

Watch this short clip as Dr. Manuel discusses the importance of the MarTID 2021 Survey: