MARKET: Why Don’t OSVs Get Scrapped?

The OSV sector will be reliant on a hitherto unseen amount of scrapping to balance the market, writes Gregory Brown, Associate Director – Offshore, Maritime Strategies International

There is a consensus that an OSV market recovery will only be driven a supply side rationalization. As well as a lack of newbuild activity, that rationalization will have to include unprecedented levels of scrapping in a market which has historically witnessed only limited levels of attrition.

That limited level of attrition has several deep-seated roots, most notably weak scrap values, a fragmented supply chain, and low idle costs (~<$1,000/day). These fundamentals are unlikely to change. Scrap prices are likely to remain weak, the fleet will remain fragmented, and OSVs will continue to be unattractive for scrap yards.

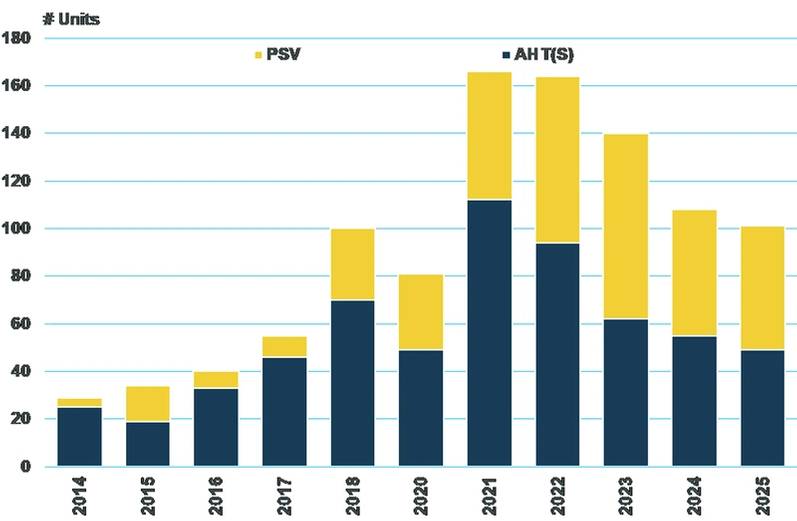

However, our base case assumes that nearly 400 AHT(S) and around 300 PSVs will leave the market between 2021 and 2025, at an average of 74 and 61 vessels per year, respectively – nearly trebling the average scrapping levels between 2000 and 2020.

Rather than a fundamental change to the scrapping market, those numbers are underpinned by a changing end-user market that will, in our view, increasingly render older vessels uncompetitive for offshore work.

Long tail of ownership

One of the reasons why so few OSVs are scrapped is the nature of the supply chain. The fleet is fragmented. There are more than 1,000 operators in the market, with the top 20 accounting for just 25% of the total supply. The drilling fleet, where scrapping levels are notably higher, is far more concentrated.

There are fewer than 200 operators, with the top 20 accounting for more than half of marketed supply. This concentration makes fleet-wide rationalization decisions considerably more straightforward as it becomes far easier to arrive at a consensus amongst a smaller quorum of interests. In comparison, the OSV space has a long tail of stakeholders, more than half of which have just one vessel. Decisions made by the likes of Bourbon and Tidewater at the top may have limited impacts on those smaller, regional players at the bottom.

Consolidation would almost certainly help the sector achieve greater capital discipline and potentially prop up scrapping levels. However, while Tidewater, Maersk, Vroon, and many others adopt wholesale restructurings to their fleets and sell more ships, not all assets are heading into the hands of recyclers. Tidewater’s recent sales have seen the likes of the Hanks Tide and Dulaca Tide sold to Baltic Marine and Hudson Offshore, respectively. DOF sold the Skandi Giant to Hai Duong in August 2020, while in June of the same year, Maersk sold the Maersk Advancer and Maersk Asserter to Karadeniz. These vessels, and many others continue to trade, lengthening the wagging tail still further.

Kim Heng has also been an aggressive buyer of tonnage from distressed sellers in the downturn. Its subsidiary, Bridgewater Offshore acquired four ships from the collapsed Teraseas business, including the Salvanguard and Salvigilant for an en bloc $4.8m price. Bridgewater also purchased the Salveritas and Salviceroy for $5.2m combined. The business has a stated intention to “invest for the future in cycle positioning so as to take advantage of buying distressed assets at significant bargains with the right value.”

With the presence of such players in the market hopes for a bout of consolidation in the space look to be forlorn.

Less attractive to recyclers

Yet another reason underpinning the lack of recycling activity in the OSV space is their relative attractiveness, and lack thereof, to recycling yards in comparison to alternatives in the shape of large, cheap drilling rigs and merchant vessels.

That attractiveness is reflected in the relatively low scrap prices achieved for AHT(S) and PSV vessels. Fundamentally, OSVs are significantly smaller and contain less valuable parts than drilling rigs or merchant vessels. This disincentivizes scrapping. Indeed, the scrap price of OSVs in Northern Europe is arguably negative.

Assuming a theoretical scrap price of $300/ldt, the average OSV scrapped between 2010-20 would be worth just $461,000 to a recycling yard, arguably lower than the repositioning costs associated with transporting a vessel. This stands in marked contrast to the ~$3-4m value of scrapped tankers, bulkers and containers removed over the same period.

Age requirements and cabotage regulations

The fundamentals behind the lack of OSV scrapping are not going to change. The vessels will remain relatively unattractive to recycling yards, and the ownership profile will still be fragmented. Optically, it may be surprising to see that our base case vessel supply forecasts include a hitherto unprecedented amount of removals from the fleet. We forecast 421 AHT(S) and 339 PSVs to be removed from the fleet between 2020 and 2025 – suggesting that, on average, 3% of the OSV fleet will become obsolete each year.

If the fundamentals behind the scrapping market are not going to change, those removals will have to be driven by outside influences. Specifically, our forecast is predicated on older vessels becoming increasingly uncompetitive in the offshore space. In Northern Europe, for example, vessels older than 15 years of age will struggle to secure utilization and will eventually fall out of the market.

Those older vessels would typically remobilize to the Far East or Middle East Gulf. The physical process of repositioning is relatively straightforward and costs between $0.1-0.3m per vessel depending on the mode of transport, weather, etc. However, the process of securing work for those vessels has become increasingly complex. Barriers to entry have increased along with greater local content (IKTVA, ICV, Tawtween, etc.), and owners are required to establish local entities and partnerships. Even then, foreign assets will be increasingly marginalized against local tonnage.

Meanwhile, stricter age requirements are serving to limit the competitiveness of older assets. ADNOC will no longer take on vessels greater than 20 years of age. Aramco will not take vessels greater than 23 years of age, and ONGC has lowered its upper age limit from 24 years in 2013/14 to 21. Acting in parallel with those age requirements is the continued shift towards vessels with lower emissions. In Norway, all vessels on longer-term contracts for Equinor in 2021 (~20 vessels) have, or will have a battery and a shore-power based system in 2021. Such modifications are unlikely to be made to older vessels.

The diminishing commercial prospects of those older vessels should drive their retrenchment from the fleet, helping to balance the market and drive an improvement in utilization, and eventually, earnings.