Demand Grows for OSVs in the Offshore Floating Production and Storage Energy Sector

Over the last year we have seen an upswing in floating production and storage systems ordering after many years of low activity. According to our colleagues at World Energy Reports, “The global oil and natural gas markets are contending with rebounding energy demand on top of supply disruptions from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. As a result, activity and business sentiment in the floating production sector has seldom been stronger.” This increased activity in the floating production and storage segment has a direct impact on OSV demand.

Today there are on average more than 700 OSVs providing long term support to floating production and offloading systems globally. Depending on daily activity the number of active OSVs can rise above 1,000 units and also fall below 375 vessels.

Our base case forecast is that around 425 additional OSVs will be required to support floating production and offloading systems currently on order and planned.

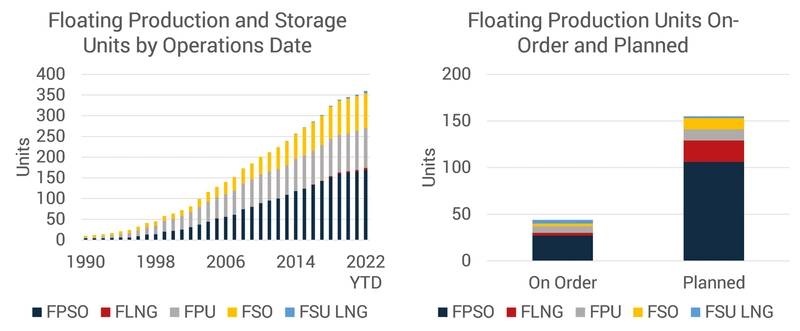

Around 360 floating production and storage systems installed globally and close to 200 on order or planned

Although we track other floating systems including floating LNG regassification units (FSRUs), this article focusses on five floating production and storage segments – floating production storage and offloading units or FPSOs, Floating LNG production storage and offloading units or FLNGs, floating production units with no storage or FPUs, floating storage units or FSOs and LNG floating storage units or FSU LNGs.

Exhibit 1 summarizes the historical development of the market which reached close to 360 installed units by the end of May of this year and the forecast development of the sector based on current orders and planned activity.

Around 47% of installed systems are FPSOs, by far the largest segment. Brazil is currently the largest market for FPSOs with 48 installed units. The influence of FPSOs becomes more pronounced when looking forward. FPSOs account for over 60% of all floating and production systems on order and close to 70% of planned units.

The FLNG segment is in the early stages of its development journey. There are currently five operational units globally. But looking forward, the segment becomes the second most prospective segment after FPSOs. The FLNG segment accounts for 26 units on order and planned or 13% of the total.

The next largest segment is floating production units without storage which cover semi-submersibles, TLPs, spars and barges. There are currently over 95 installed units globally, 50 of which are installed in the Gulf of Mexico. Of the 19 FPUs on order or planned, eight will be deployed in the Gulf of Mexico and three in Australia.

FSOs account for close to 85 installed units today with deliveries of FSOs slowing of late. 15 FSOs are currently planned or on order.

Like the FLNG segment, the FSU LNG segment is relatively small with six units currently operational. We anticipate that the segment will double in the coming years with a further six units planned or on order.

Where are the opportunities for OSVs?

At a high-level one can group OSV opportunities in the floating production and storage segment into three activities –- moving the unit, supporting installation and long-term production support.

- Moving the unit

Whereas units are deployed globally, hulls are often built or converted in Asian yards. Drilling down into the FPSO segment, around 150 hulls have been moved from Singapore, China and South Korea. The UAE, Malaysia and Brazil are smaller but significant yard players. In other segments Singapore and China account for the largest origin for FSO hull tows and Singapore and South Korea for FSU LNG hull tows. For FPUs, South Korea is the leading semi-sub and TLP origin and Finland historically for spars.

By far the most popular way to move a floating production system is by wet tow with large ocean-going towing tugs. Dry towage and self-propulsion remain an option and large heavy lift vessels have been deployed to move floating production hulls. However, there remains a limited choice of suitable heavy lift vessels, especially for the largest units.

Our analysis indicates that wet tow activity generally calls for two-to-three 200± tonnes bollard pull main towing vessels. Escort tugs can also be deployed. Exhibit 2 shows our analysis of towing tugs that have deployed to move FPSOs.

When analyzing the movement of semi-submersibles, the largest of the FPU sub-segments, we note an average two towing vessels ranging from 200 to 340 tonnes bollard pull for units with 100,000 barrels per day process capacity.

- Installation support

Ahead of a floating production system’s arrival at site, mooring systems will already have been pre-laid by very large AHTSs and offshore construction vessels.

Once the floating production system arrives at site, the towing tugs that brought the unit to the site are often used to support heading control during hook-up connection work as well as disconnection work when the unit leaves the field. In the case of FPSOs, FLNGs and FSOs this can require up to five large sized towing tugs. Smaller OSVs are often deployed for logistics support and security, fire and/or pollution control stand-by.

- Long-term operational support

Depending on client and location, in terms of long-term support OSVs can be dedicated to the floating production system or where one client is supporting a significant amount of offshore infrastructure, such as Petrobras in Brazil, some vessels can be shared across several units.

The main activities of OSVs during the production phase of the floating production systems cover general supply duties and security, safety and environmental control.

For those systems with storage, offtake support includes pilotage, mooring hawser and hose handling, ferrying manifolds, parallel and tandem mooring. Different environmental conditions as well as size or type of shuttle tankers result in some regional variations in the types of anchor handlers seen supporting floating production systems. As an example, conventional tankers with midship manifolds are more commonly found in Africa whilst DP shuttle tankers with bow loading systems have typically but not exclusively been deployed in Brazil. The different conditions impact the specific offtake operations.

Using the largest floating production and storage segment, FPSOs, Exhibit 3 summarizes the sizes of anchor handlers and PSVs deployed in long-term support operations by major region.

Brazil and Africa are the largest FPSO markets for OSVs. It is worth noting the concentration of large anchor handlers in Brazil from around 150 to around 210 tonnes bollard pull, whereas the spread of sizes found in the large African market is significantly wider. For PSVs, there is less of a clear correlation of vessel size to FPSO storage or processing capacities. At a high-level we can say that 3,000-5,000 plus dwt PSVs are used for FPSO support, generally in the larger markets such as Africa and Brazil. Other OSVs are often deployed for security, fire and/or pollution control stand-by.

How big is the opportunity for OSVs?

Based on our analysis of existing operational practices and our forecast of planned and on order floating production and storage systems, Exhibit 4 summarizes our long-term demand forecast of OSVs to support operations.

Our base case identifies a demand for around 425 units.

Potential for large anchor handler supply tightnessIncreased exploration and production activity is a trigger for increased drilling rig utilization, which is also a trigger for AHT, AHTS and PSV utilization. The OSV fleet was built to support oil & gas activities and with the reactivation of idle vessels and even some new building supply and demand may find some balance.

However, we believe that there is an emerging new demand for large anchor handlers for which there is insufficient vessel supply –- floating offshore wind farms. Pre-commercial floating wind turbine arrays are already being installed and large commercial projects of 500-1,000 MW are in planning for installation towards the end of the decade.

Floating wind arrays deploy floating substructures which are generally semi-submersible, spar or TLP concepts designed to support the latest generation of wind turbine which has a capacity of around 15 MW, which means around 66 wind turbines will be installed on a 1 GW wind farm. Each substructure is moored to the seabed with at least three mooring lines. The largest anchor handlers have been deployed to date to install mooring, tow and hook up floating wind structures. Exhibit 5 summarizes the size of anchor handlers deployed on floating wind projects to date and compares a typical floating wind farm with a typical deep-water FPSO. One offshore wind farm consumes around five times more mooring line and up to 12 times more anchors than the FPSO project.

We see the challenge in the 16,000 bhp or 200 tonnes bollard pull anchor handlers and above segments. There are about 155-175 active anchor handlers and around a further 40 vessels in lay-up in this segment. With limited new building activity committed there is a potential supply shortage past the middle of the decade. This becomes a driver for a tight market, higher day rates and new building, especially for vessels featuring diesel electric, hybrid or fuel cell systems or vessels operating on low or zero caron fuels.

- For more information about the World Energy Reports Monthly Floater Report, please visit www.intelatus.com or contact Michael Kozlowski at +1 561-733-2477 or Philip Lewis at +44 203-966-2492.

About the Author

Philip Lewis is Director Research at Intelatus Global Partners. He has extensive market analysis and strategic planning experience in the global energy, maritime and offshore oil and gas sectors. Intelatus Global Partners has been formed from the merger of International Maritime Associates and World Energy Reports.