Back to the Drawing Board: Pondering Truths in Design

In producing a column for the Marine Design issue, I considered a number of subjects, but in starting to write about them, somehow my mind connected to “Beam is Cheap.” I have a faint memory of being made aware of this during a discussion of a ship design by a design luminary very early in my career, but I don’t remember who it was.

When first putting pencil to paper on some design, I always think about that when I make my first rough sketch. It is a very powerful truism, and over the years I have seen it applied quite effectively quite a number of times.

The weird thing about this truism is that it may never be apparent to a young Naval Architect until somebody mentions it and then she will go: Hmm, yes, wow! Yes, beam is cheap!

Even when the problem is discovered after the vessel has been built, sponsons are often the only cost-effective fix, and, while not exactly pretty, they are quite cheap compared to all the alternatives.

Since my “Beam is Cheap” discovery, I have run into others truisms, but most are detail truisms. Such as: I can always make a more efficient structure in cold molded wood than standard fiberglass, or engines burn ½ pound of fuel per horsepower per hour.

There are fewer design truisms that can be applied in a more general fashion.

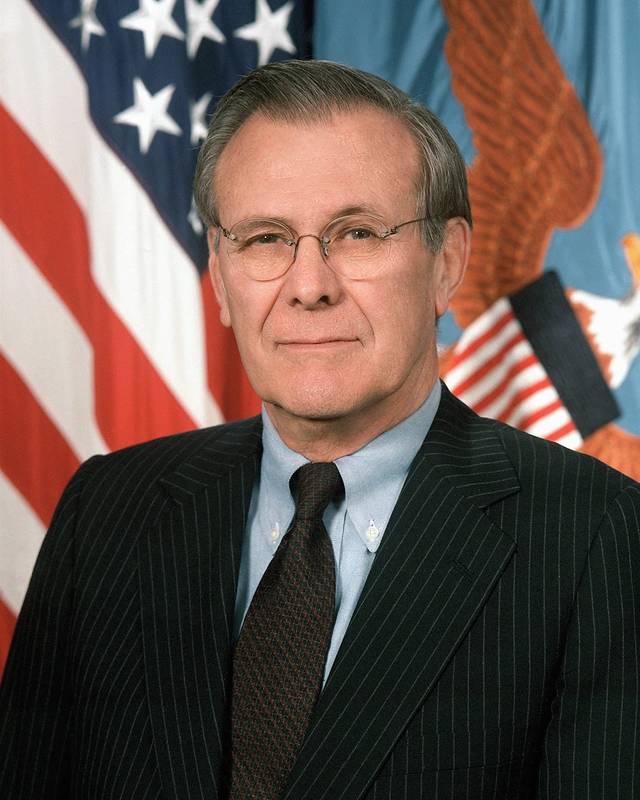

I will discuss two of them. The first one is relatively famous, but not generally considered to be a design truism. It is the Rumsfeld matrix.

He provided that matrix when asked about the lack of evidence linking the government of Iraq with the supply of weapons of mass destruction to terrorist groups. Rumsfeld waffled about providing an answer, but, oddly, his deflection was quite true. He said:

“Reports that say that something hasn't happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don't know we don't know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tends to be the difficult ones.”

Rummy cast his comment in the realm of historical evaluation, but that is just hindsight. Designers engage in foresight and every designer deals with the Rumsfeld matrix.

You always design based on things you know, and you avoid the things you do not know; but you cannot prevent getting bitten by the things you do not know you do not know.

In our presently very rapidly changing technological world (and, trust me, it is changing faster today than in the last 40 years in my career), we will be faced with many unknowns we did not know we did not know.

This is something all designers (engineers) live with and the great engineer, and president with bad timing, Herbert Hoover, expressed it as:

“The great liability of the engineer compared to men of other professions is that his works are out in the open where all can see them. His acts, step by step, are in hard substance. He cannot bury his mistakes in the grave like the doctors. He cannot argue them into thin air or blame the judge like the lawyers. He cannot, like the architects, cover his failures with trees and vines. He cannot, like the politicians, screen his shortcomings by blaming his opponents and hope that the people will forget. The engineer simply cannot deny that he did it. If his works do not work, he is damned.

That is the phantasmagoria that haunts his nights and dogs his days. He comes from the job at the end of the day resolved to calculate it again. He wakes in the night in a cold sweat and puts something on paper that looks silly in the morning. All day he shivers at the thought of the bugs which will inevitably appear to jolt its smooth consummation.”

Exactly the same sentiment, but in much more elegant language. I mean “Phantasmagoria;” you can look it up in the dictionary, but, most of all, I can hear you trying to pronounce it and failing.

The life of an engineer appears to be so hopeless, but then we have John Boyd. John Boyd developed the OODA loop. It was developed by him in fighter plane combat training, and is now applied in other combat activities. It is incredibly simple, but, just like “Beam is Cheap,” once you dial into it, it becomes super powerful.

OODA stands for Observe, Orientate, Decide and Act, and then do it all over again right away.

So, this is what happens to a novice in the cockpit. He’d observe enemy fighters, and then will freeze in panic not knowing what to do until he gets shot down. (This weird paralysis also tends to affect new engineers.)

Instead, John Boyd would train the novice to observe, to figure out where the problem was, to engage the option that is most effective under the circumstances, to take action and to see what happened after the action was taken, and start the loop all over again. That makes sense, but what is really interesting is that it gets to be real fun when you can do the loop faster than the enemy, whether the enemy is a bunch of other fighter pilots, a bunch of pirates, or a sinking ship.

Once I became familiar with the concept, I realized it is central to ship dynamic design, such as design for proper maneuverability or salvage response, and one can even score the effectiveness of a design, or compare designs, with a simple equation:

What is even stranger is that, to some extent, OODA is a trip around the design spiral, but by focusing on getting around the spiral faster, one can make faster progress; and this was expressed by another great engineer, Admiral Wayne Meyer, the father of the Aegis combat system. His mantra was: “Build a little, Test a little, Learn a lot.”

In a design context, he is simply stating: For greater effectiveness do a lot of fast OODAs and forget about doing one big OODA, because by the time you are done with the big loop the march of technology has gunned you down.

What is even more interesting is that by using Boyd/Meyer it becomes easier to manage the unknowns we do not know we do not know. (Big steps result in skipping lots of cracks in the pavement.) By rapidly taking small steps there will be fewer unknowns we did not know we did not know that become apparent, and that allows us to manage the process, by, for example ... increasing beam a little.

As I said, I do not remember from whom I learned about beam is cheap. I do remember where I learned about “build a little, test a little, learn a lot.” My father was working on a multi-billion dollar international navy bribery investigation and was working with a retired admiral. My father kept saying I should meet him since he was a wonderful engineer. In my mind admiral and engineer are an oxymoron; and when I met him in the office, I shook hands and exchanged pleasantries, but must admit I did not make a significant effort to become more acquainted with him.

A few months later my father told me the admiral had invited him as his guest to a destroyer christening. I said: “Nice, what is the vessel’s name?” My father said: “Wayne Meyer.” I said: “Yes, I know that Wayne Meyer invited you, but what is the ship’s name.” My father simply repeated his answer with more emphasis (and proper parental contempt) and that resulted in me rushing to my computer to google Wayne Meyer and discover his mantra.

Unfortunately, I never got to meet him again. But design truths never die.

For each column I write, MREN has agreed to make a small donation to an organization of my choice. For this column I select the American Society of Naval Engineers scholarship fund. We need more great admiral engineers. www.navalengineers.org