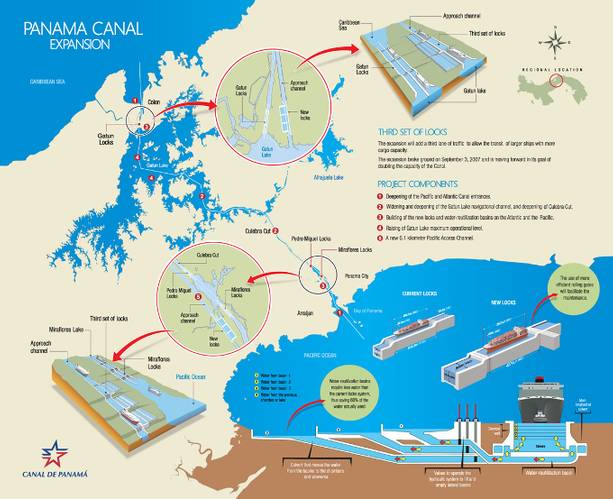

The Panama Canal has linked the Pacific with the Atlantic for more than 100 years. It will soon be possible for significantly larger ships to pass through its locks. What will the expansion mean for Hapag-Lloyd?

They’re still working in Panama, on one of the biggest construction sites in the world. Everything seems gigantic here. The lock gates alone, veritable monsters of grey steel: 16 in total, each of them 57 meters long, averaging 30 meters high, ten meters thick and weighing 3,300 metric tons. They were brought by special ships from Italy to the jungle of Central America.

A total of 4.4 million cubic meters of cement has been poured here since the first turn of the shovel – more than was used to construct the canal over 100 years ago. And almost the same amount of earth is being moved once again as it was back then – around 150 million cubic meters. The reopening has been delayed again and again.

Regardless of when it’s finished, the expansion of the Panama Canal is likely to mean one of the biggest changes for the global shipping industry this century. This is because the bigger locks mean that as well as conventional vessels, much larger container ships will also be able to cross the Isthmus of Panama. But how will the liner services that travel through the canal be organized in future? And how big should the ships be so that their capacities are optimized?

It’s a game involving many variables. Along with Hapag-Lloyd, all the other players in the industry are now reshuffling their cards. Whoever arranges them most effectively can gain a considerable advantage. Far more important for the replanning than the expansion of the canal itself is the question: which ports in the neighboring regions of North and South America are able to efficiently handle the bigger ships? Which ones are planning to have longer quays, deeper basins and larger container cranes – and when will they be ready for use? The expansion of the Panama Canal has set in motion a whole chain of logistics projects. And they aren’t always completed on time. For example, the Bayonne Bridge at the entrance to the important Port of New York will not have the higher clearance needed for bigger ships before 2017.

One of the most important decisions in terms of the new opportunities was taken back in April 2015, when Hapag-Lloyd ordered five new container ships, each with a capacity of 10,500 TEU. The order was in response to the question: do we have the right ships? Hyundai Samho Industries will deliver the vessels, which are from the new, efficient Valparaíso Express class, between November this year and February 2017 – in time for the reefer season in South America at the start of the year. With 2,100 connections each for reefer containers, they are perfectly suited for this trade. At 333 meters long and 48 meters wide, the Valparaíso Express vessels and their sister ships will be able to pass comfortably through the new locks.

Hapag-Lloyd travels through the canal with its own ships on a total of ten services at present – five of its own and a further five as part of the G6 Alliance. This has meant an annual transport volume of around 800,000 TEU up until now, a good 10 percent of Hapag-Lloyd’s total cargo volume. The canal authorities in Panama themselves expect the volume of goods transported through the Panama Canal to climb from three per cent at present to around five per cent of the total global volume carried by ship.

In future, Hapag-Lloyd will only continue to use the current Panamax vessels on the PA1, the former PAX service, and on the MPS between the west coast of the USA and Europe. This is also because these vessels have onshore power connections, which are important for port calls in California in particular. With a view to the future, Hapag-Lloyd decommissioned a further 16 older Panamax vessels last year, selling some of them and disposing of some of them in an environmentally responsible manner.