Globalization is the driving force of container shipping, as ever more goods are transported across the world’s oceans in steel boxes on ever-larger container ships. But container shipping is also what made globalization possible in the first place.

The principle of division of labor is nothing new to us today. In 1776, the economist Adam Smith, a formative thinker of the free market economy, elucidated this concept in his book, The Wealth of Nations. The operative principle is that the employees of a company divide up different tasks and thereby increase their productivity. Companies today continue to operate according to this principle, albeit on a much larger scale than in the past. They seek their workforce, raw materials and expertise, as well as their customers and suppliers, around the world.

On the other hand, the proximity of production sites to sources of raw materials or to sales markets is no longer crucial. But how has labor as a production factor become uncoupled from the previously decisive factor of proximity to the sales market? Globalization can be illustrated well through the example of the value-added chain of a T-shirt, which is a global product. From the cultivation of the raw material cotton to the manufacturing and sales process, the material travels around the world. About two thirds of the cotton produced in the U.S. is exported – particularly to Mexico and Honduras, the “sewing rooms” of the U.S. clothing industry.

But millions of bales of cotton also travel by container ship to China, the world’s leading producer of cotton products. In the factories there, cotton is spun into cloth, which is then sewn into T-shirts and jeans. The finished clothing then ends up back on a container ship to travel to its sales market: for example, crossing the Pacific and the Panama Canal in 30 days to reach the southern U.S. – the very place where the raw material for the garments was harvested and shipped off to Asia a few months earlier. A T-shirt that costs $10, $20 or $30 in a store incurs costs of less than $0.10 for its entire transportation chain, from the cotton field to the clothing store. If more than 30,000 T-shirts are shipped from China to Germany in a 40-foot container, the freight costs total less than $0.01 per garment, an insignificant amount in comparison to the product’s total costs.

The use of enormous freight containers has, alongside other factors, increased productivity in the supply chain – shorter 20-foot containers and today, above all, 40-foot containers. In the 1950s and 60s, a 160-meter general cargo ship with a crew of 42 could move a total of almost 85,000 tons a year in cargo between Asia and Europe. Today, a 366-meter container ship such as Hapag-Lloyd’s Hamburg Express with a crew of 24 and enough space for 13,200 standard containers (TEU) can manage more than 1.3 million tons per year – thanks to a load capacity of more than 140,000 tons.

The container’s serious boost to productivity does not end with the cargo ship, but rather continues on the quay. In the days when seafaring still had a whiff of romance and a general cargo ship often sat in port for several weeks, it took an entire shift to move 45 tons of cargo with 22 workers and a crane. Now a container gantry crane driver can take care of this task within a minute. This is all the time that is needed to unload two 40-foot containers. When the Hamburg Express docks at the container terminal in Hamburg Altenwerder, more than 5,000 containers are often unloaded and loaded, moving a total of more than 85,000 tons over the quay – in just 36 hours. Five crane operators per shift complete this task using a joystick.

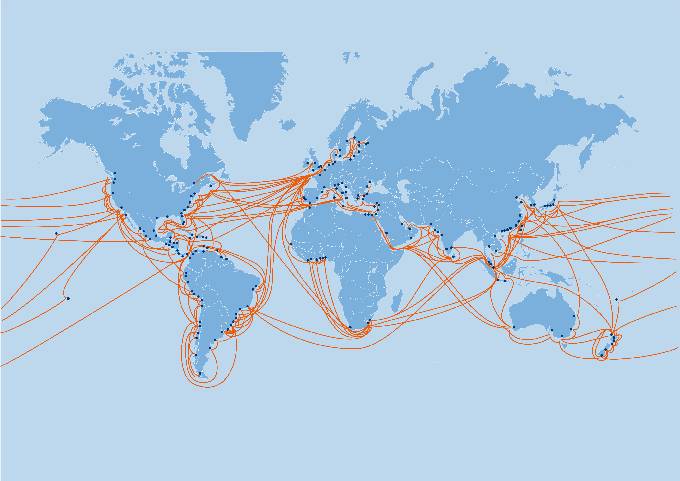

These container shipping figures have greatly accelerated global trade since the introduction of steel boxes. In 2014, some 171 million TEU were shipped across the world’s oceans. Further growth is predicted for the coming years.

In short, the advent of the container was one of the necessary conditions for a global division of labor and the container ship was a catalyst of globalization. It meant that it no longer mattered where the raw material had to be shipped from to reach the production site, nor did the distance to the sales market matter. Shipping a pair of sneakers from Vietnam to Germany costs just $0.25 to $0.30, while shipping a flat screen TV from South Korea costs two to three euros, and Apple iPads travel from Asia to Europe for about $0.25 each.

Conversely, the triumph of the container has also opened up unimagined new markets to Western producers. And smaller businesses are no longer dependent on their local markets: today a vintner can have his wines transported from his bottling plant to the central warehouse of a Tokyo supermarket for about ten cents a bottle.

Perishable fruit can also travel halfway around the world these days, thanks to reefer containers. 800,000 containers of bananas alone will travel from the world’s plantations to its supermarket shelves this year, as will a great many avocados from South Africa, grapes from Chile and apples from New Zealand.

By the way, according to studies, the carbon footprint of an apple from New Zealand or a steak from Australia can, depending on the season and the production conditions, be smaller than that of an apple from Lake Constance or a steak from eastern Westphalia – despite its sea journey of 13,000 nautical miles or 24,000 kilometers. That, too, is globalization.