Poor Conditions, Better Communications

Industry and the federal government continue to work together to improve less than optimal conditions on the U.S. inland waterways. Measurable, although slow progress is being achieved.

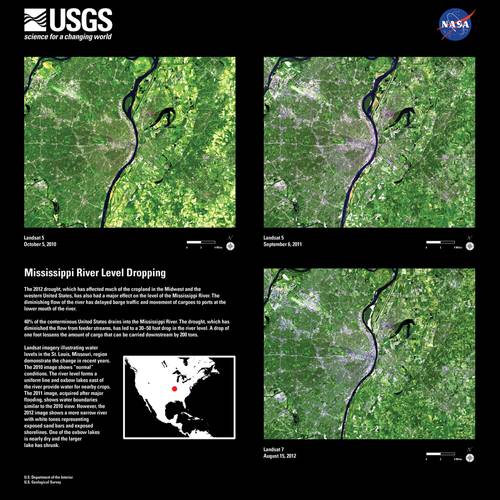

The summer of 2012 brought drought and poor navigating conditions to the inland waterways. Low water levels continued into the fall and threaten to move into winter, but the event has demonstrated how barge industry and government relations have changed over the years and what challenges remain.

“We’ve gone from the Great Flood to the Great Drought,” said Dan Mecklenborg, Senior Vice President at Ingram Barge Company. Water gauges on the Mississippi River at Memphis, Tenn. were 50 feet lower this year than they had been one year ago during the 2011 flood. If you want a silver lining, it could be that the industry “had a lot of practice working with the Corp and the Coast Guard last year with the high water,” said Lynn Muench, Senior Vice President of Regional Advocacy at the American Waterways Operators (AWO).

Because of last year’s flood, many resources and communication strategies were already in place to deal with this year’s poor river conditions.

Austin Golding of Golding Barge Line said “the Corp has done a fantastic job of getting out to reported areas and dredging.” Golding sits on the AWO’s board for southern regions. His approval of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ (USACE) management of the drought is largely shared by the rest of the industry, except when it comes to the flow of the Missouri River into the Mississippi.

“This year our concern is that the Corp has been reducing the flow from the Missouri River,” Mecklenborg said, directly impacting the middle section of the Mississippi River between St. Louis, Mo. and Cairo, Ill. “We’re concerned that we could end up with low water through December.”

Light Loading & Infrastructure Failures

“We have been living with low water situations on the Mississippi River System starting with the Ohio River in mid-May and extending to the upper and lower Mississippi River during the third quarter,” said Steve Holcomb of Kirby Corporation. Hurricane Isaac resulted in small gains for the Mississippi in September, but not nearly enough. The situation continued to get worse until mid October when water levels began to recover slightly, but conditions were still well below normal as this went to print.

“Transit times have been extended due to the low water levels and numerous industry groundings, occasionally closing sections of the river for short periods of time and dredging throughout the system,” said Holcomb.

The upper Mississippi with its locks system is less impacted. Boats on the upper portion of the river push a maximum of 15 barges in a tow even under normal conditions, due to the limited capacity of lock chambers. Also, petroleum products have been less impacted than dry bulk cargos. “It’s a dimension issue,” Mecklenborg said. Liquid tows use different sized barges and are hauled in smaller tows, so narrowing channels are less of a problem. But for dry bulk cargo carriers, from St. Louis to the Gulf, the situation has been most difficult.

Under normal conditions, “on the lower Mississippi, our members would load to a draft of close to 12 feet and have 35 to 45 barges in a tow,” said Muench. “Right now they’re loading at less than nine feet and most only have 20 barges in a tow.”

The AWO put the loss of cargo capacity into perspective. A three-foot loss of water equates to losing 612 tons of cargo per barge, the organization said. When also reducing the tow by 15 barges, this can equate to a loss of 9,100 tons of cargo. Switching to roads to move the left behind cargo would be difficult because each tractor trailer carries far less than one barge. An additional 360 semi-trucks would be needed on the roads to move those 9,100 tons.

To make matters worse, low water levels are compounded by an increasingly decrepit locks system.

“Lock 27 just north of St. Louis, the most southern lock on the Mississippi, went down with an emergency closure recently,” said Muench. “It’s particularly a problem this year because the industry is already struggling with not hauling as much.”

Officially there were 63 tows reported in the queue during that particular outage, she said, but there were probably at least 90 waiting on the river somewhere, knowing the lock area was jammed with boats. “It took them five days after the opening of the lock to get back down to a normal wait time.”

Considering that it has been estimated to cost a barge company $10,000 a day when a towboat sits idle, not including the costs associated with idle barges or cargo, this kind of outage makes a big impact.

Speaking of the barging industry, Mecklenborg said “we move 15% of all the freight transported in the U.S. and we do it at a cost that’s about 3% of the total U.S. freight bill. We also have the best fuel utilization rate. We move one ton of cargo over 600 miles on one gallon of fuel.”

Golding echoed the sentiment of the entire barging community when he said “I’d like to see the waterways kept updated and see our locks and infrastructure improved. As we update our fleets on our end, the locks and dams need to be updated too.”

A New Era: Industry & Government – Together?

The last time the inland waterways faced a drought this severe was in 1988, an event which was estimated to have cost the barge industry $1 billion. During that drought, the river channels were not as well managed and the different subsets of the Corp did not communicate well, Muench said.

“That’s one of the reasons the river shut down as long as it did back then. It was very similar to the flows we are experiencing now, but with two big differences: structural improvements and communication between the AWO, Corp and Coast Guard.”

There was a great deal of anger and frustration between industry and government back then, Muench said, caused by a stovepipe approach to inland waterways management. “As I understand it,” she said, “they were dredging things that weren’t critical instead of sending resources across district lines.” But now “there’s discussion on how to reallocate things and this time all the assets are being deployed based on system needs, not stopping at district lines.”

Much of today’s improved communications are achieved through the River Industry Executive Task Force made up of the Corp Generals for the Mississippi Valley, Great Lakes and Ohio River divisions; the Coast Guard Admirals of the 8th and 9th districts; and seven senior executives from AWO.

“We’re on a conference call with them on a daily basis, depending on the section of river, to identify where there are problems. We’re talking about how to keep safely moving, setting up cues and what buoys might need to be reset because the river is changing. If industry is seeing a place that needs to be dredged soon, we’re notifying the Corps and Coast Guard because they don’t have the resources to monitor everything,” Muench said.

Today, she adds, “there’s more of an understanding that we’re all doing the best we can. It’s Mother Nature that’s not cooperating. Even if things aren’t perfect, if you understand what the challenge is, that’s workable.” In addition to the communications improvements that came about after the 1988 drought, the Corp completed river work that allowed the water to move quicker to the middle of the channel and kept the silt from building up. Consequently, Muench said, it takes less dredging than it did in the 80s to manage drought conditions.

Contentious Missouri River Flow

The Missouri River comes into the Mississippi just above St. Louis. “What we call the lower Mississippi could really be called the lower Missouri based on the amount of water that comes from that river,” said Muench. From St. Louis, Mo. to Cairo, Ill. the Mississippi is largely fed by flow from the Missouri River. The Corp provides flow from the Missouri basin reservoir into the Mississippi from April 1 to December 1.

“On a normal year, I’ve typically seen estimates that 20% to 30% of the water going past the arch in St. Louis is from the Missouri River.” This year however, “almost 70% of the water going past the arch is coming out of the Missouri.”

“Without the Missouri River release this year the St. Louis harbor would be closed, cutting off the lower Mississippi from the upper portion of the river and from the Illinois River. The area from St. Louis to Cairo would also be closed; a section relied upon by major agricultural producers. There are also a lot of petroleum and chemical producers that travel the Illinois, into and out of the Chicago area, that would be impacted,” said Muench.

But even the current release from the Missouri River does not support full-service navigation on the Mississippi and so far the Corp has been unwilling to release more. Ironically, the Missouri River is managed by the Northwestern division of the Corp, based in Portland, Ore. “We have asked that the Missouri River release more water,” Muench said. She believes the Corp is obliged to release enough water to support full-service navigation on the Mississippi, but “the Corp says they are not.”

“The Corp is still telling us that they cannot and will not release water for Mississippi River navigation even though the President clearly stated that they should be. That’s part of the President’s promise to increase exports.” What’s more, said Muench, “there were five or six lawsuits combined into a 2005 court case that said navigation and flood control are the two primary purposes of the Missouri River system and water should be released for ‘downstream navigation.’”

The question is, does “downstream” include what we call the lower Mississippi? Even more disconcerting than the refusal to release more water is the prospect of what happens if the river levels do not recover enough to maintain safe navigation after the flow cutoff date in December. “We’re really, very concerned about Dec 1,” said Muench.

Only time will tell what water levels do this winter and if the Corp’s Northwest division decides to release water beyond the traditional cut off. As light loading and infrastructure woes continue, “All I can say is that luckily today it’s raining here in St. Louis,” Muench said, “but we need a lot of rain to catch up.”

Looking Ahead

The U.S. inland waterways system is challenging enough, even in the best of times. Continued improvement in industry-government relations, plus a little bit of luck from Mother Nature herself, will go a long way towards rectifying some of the worst navigation conditions seen in decades. Even minor improvements in both metrics will produce measurable progress. The latter variable can’t be controlled with any reliability; the former probably still needs work. Navigating in that direction is something we can all look forward to.

(As published in the November 2012 edition of Marine News - www.marinelink.com)